A $7.5 million award will help researchers harness the body’s own defenses to counteract nerve agents and create new types of antidotes for exposure to pesticides and other poisons.

The grant, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), extends a previous grant and establishes a new Center of Excellence at Ohio State University, where chemists will collaborate with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md., and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

At the new Ohio State center, chemists Thomas J. Magliery and Christopher M. Hadad will lead a team that employs sophisticated methods of protein engineering, high-throughput screening and computational chemistry at the university and the Ohio Supercomputer Center (OSC). Their goal is to improve enzymes’ ability to destroy a broad array of chemical agents inside the body.

Magliery is an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and Hadad is a professor of chemistry and associate dean in the Division of Natural and Mathematical Sciences of the College of Arts and Sciences at Ohio State.

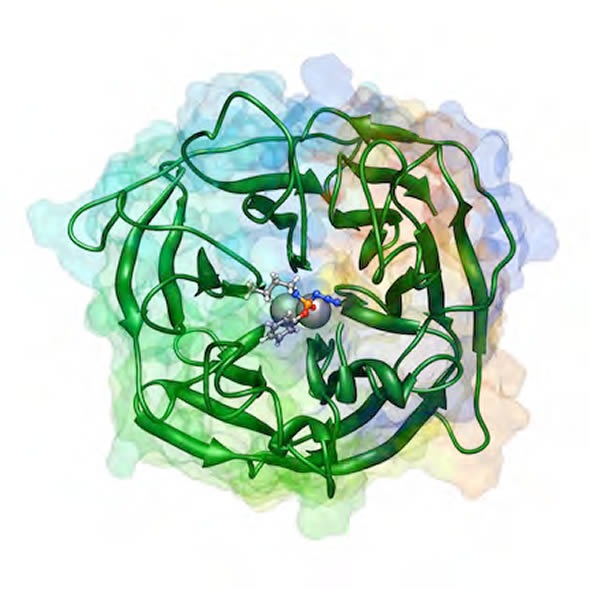

Using computational chemistry to help develop new antidotes for nerve agents, Christopher Hadad, Ph.D., professor of chemistry at The Ohio State University, leveraged Ohio Supercomputer Center resources to create this molecular dynamics model of paraoxonase bound to a ligand. (credit: Hadad/OSU)

“Dr. Hadad’s research group is consistently one of the largest and most sophisticated user groups of computing cycles at the center,” said Ashok Krishnamurthy, interim co-executive director of OSC. “It is gratifying for OSC to provide him with the resources that helped formalize such an important collaboration. Hopefully, it will lead to significant steps toward counteracting these toxic agents.”

Nerve agents are chemicals that attack the nervous system, causing paralysis and seizures and –ultimately – killing the victim through asphyxiation. They do so by bonding with the enzyme acetylcholinesterase so that it can’t transmit chemical messages from the brain to the rest of the body.

Once attached to the enzyme, nerve agents can’t be removed, explained Magliery. So the researchers are focusing on ways to stop the deadly chemicals before they can attach in the first place. They have engineered souped-up versions of naturally occurring human enzymes that will scavenge nerve agents from the bloodstream. No tests involving actual nerve agents will take place at Ohio State.

“Nerve agents like sarin, and even related pesticides, are a significant threat in the hands of terrorists, and we’re really lacking in ways to treat mass casualties,” said Magliery, co-leader of the new Ohio State center. “Fortunately, there are enzymes already in human blood that can deactivate these agents. We just have to engineer them to be more efficient, and we have to be able to produce and formulate them as drugs.”

Hadad leads an effort to model the chemical structure of candidate enzymes on the powerful parallel supercomputer systems at OSC, while Magliery is producing synthetic versions of the new enzymes for further testing and preclinical evaluation by the Army.

“The preliminary results from the first round of this grant showed that these enzymes can be engineered to have enough activity to use as therapeutic agents,” said Magliery. “But there are still challenges ahead. There are a lot of related agents, and there are few enzymes used as drugs today.”

Hadad outlined one of the main challenges. “In nature, each enzyme generally has only one function – one thing that it does very well,” he said. “But we need an enzyme that will deactivate many different nerve agents.

“We need one molecule that can do it all.”

Magliery added that the ideal enzyme would remain active for days or weeks at a time, pulling toxic agents from the body over and over again. It could be administered as an antidote immediately after an attack, or as an inoculation against future attacks. Soldiers and first responders are among the likely recipients of such a preventive dose, but so are people whose jobs regularly expose them to nerve agents, even in small quantities. For instance, 300,000 American farm workers suffer pesticide poisoning each year, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Household pesticides pose the same dangers, so an enzymatic drug could save lives in poison control centers as well.

The new NIH funded organization, dubbed the Center for Catalytic Bioscavenger Medical Defense Research II, is led by principal investigator Douglas M. Cerasoli of the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense. Magliery is the co-principal investigator of the center. The project is funded by NIH’s Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats (CounterACT) Program. The program is the centerpiece of the Department of Health and Human Services’ efforts to develop and improve treatments for chemical agents that could be used in terrorism or might be released in industrial accidents or natural disasters.