It's not uncommon these days to find a colored ribbon representing a disease. A pink ribbon is well known to signify breast cancer. But what color ribbon does one think of with lung cancer?

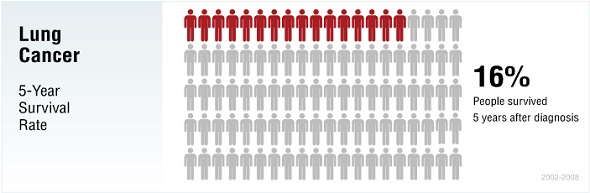

Graph showing the most recent NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data of estimated 5 year survival rate in lung cancer. For the years 2002-2008, 16 percent of people survived 5 years after diagnosis.

Although white has been identified as the designated color, for many suffering from the disease, black may be the only one they think fits.

A Michigan State University study consisting of lung cancer patients, primarily smokers between the ages of 51 to 79 years old, is shedding more light on the stigma often felt by these patients, the emotional toll it can have and how health providers can help.

"It's eye opening when a patient says to you that they feel like lung cancer 'just gets shoved under the rug,'" said Rebecca Lehto, who led the project and is an assistant professor with MSU's College of Nursing. "Patients in one of the focus groups actually associated lung cancer with a black ribbon."

Previous research has shown that lung cancer carries a stigma. Because lung cancer is primarily linked to smoking behaviors, the public's opinion of the disease can often be judgmental. Today, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death globally.

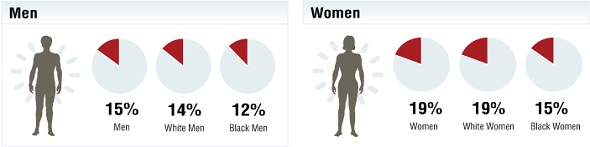

Graph showing the most recent NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data of estimated 5 year survival rate in lung cancer for men and women overall and by race.

Yet Lehto indicates that up to 25 percent of lung cancer patients worldwide have never smoked. The World Health Organization has identified air pollution as a cause, and genetics also have been associated with the disease.

"No matter how a patient gets lung cancer, it shouldn't affect the care they receive or the role empathy should play," she said.

Lehto's goal is to raise awareness among health care providers about the additional burden stigma places on patients and develop patient care strategies that strengthen coping skills and symptom management.

"Understanding a disease from the patient's perspective is essential to providing the best medical care to anyone," she said.

The study evaluated feedback from four focus groups; a format Lehto suggests is uncommon in this particular area of research.

"There've been several studies examining lung cancer stigma, but most have relied on survey data" she said. "Most of the groups in this study had three to four people participating and relied on a group dynamic to foster discussion. The sessions actually appeared quite therapeutic-acting more like a peer group." Lehto's key findings showed participants expressing guilt, self-blame, anger, regret and alienation relative to family and societal interactions. Yet, many also discussed feeling uncomfortable with their health care providers and even feared their care might be negatively affected because of their smoking background.

Although she admits more research is needed with larger, more diverse patient samples, she said her findings can help substantiate the patient perspective on a critical issue that is of sociological importance. Lehto hopes the results will encourage health care providers to examine their own perceptions about lung cancer stigma and be more aware of how it impacts the patient.

"Arming providers with rich, contextual information may help us put biases aside and heighten empathy and understanding," she said. "That would be a step in the right direction."