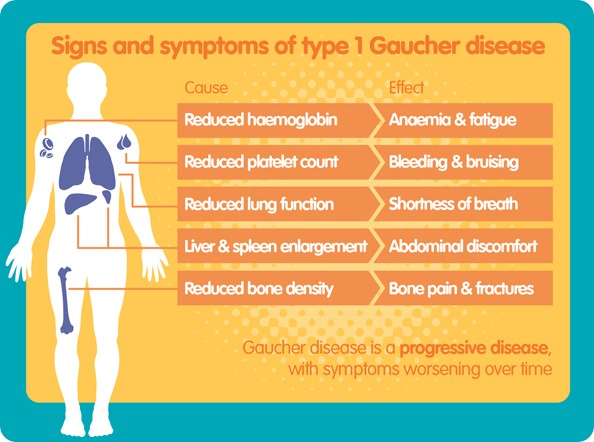

Gaucher disease is the most common condition within a family of rare diseases known as the lysosomal storage diseases. The disease causes lipids to accumulate in cells, which is why it is referred to as a storage disorder. The accumulation occurs mainly in the spleen, liver, and bones, but may also occur in the lungs, heart, and central nervous system.

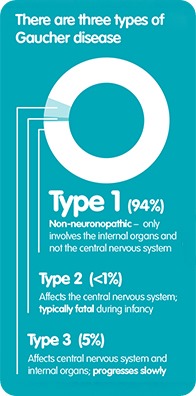

Gaucher disease occurs in three different forms, referred to as types 1, 2, and 3. Type 1, which is the most common form, accounts for 90% of cases. It is also referred to as the non-neuropathic type because it involves internal organs, such as the spleen, liver and bone, but not the central nervous system.

Types 2 and 3 are much less common and, together, they only affect around six percent of patients in total. Type 2 affects the central nervous system and onset begins during infancy. Sadly, children typically die at an early age when they are affected by Type 2, usually by around the age of two years old.

Types 2 and 3 are much less common and, together, they only affect around six percent of patients in total. Type 2 affects the central nervous system and onset begins during infancy. Sadly, children typically die at an early age when they are affected by Type 2, usually by around the age of two years old.

Type 3 also affects the central nervous system, but the signs and symptoms are similar to Type 1 and the disease tends to progress slower than Type 2, with neurological symptoms tending to appear at a later stage in childhood.

How many people are affected by the different types of Gaucher disease?

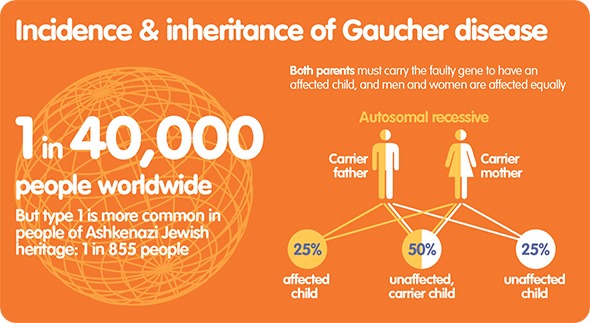

In terms of the general population, one in 40,000 people are affected by the disease. A disease is defined as rare when it affects fewer than one in 2,000 people. Compared with the general population, the incidence of type 1 Gaucher disease is significantly higher among the Ashkenazi Jewish population, where type 1 affects approximately one in 855 people. Research has shown this is caused by close heredity.

With inherited diseases, particular mutations associated with the disease can occur more commonly in a specific population. The reason for this is that people in the same ethnic group often share specific versions of genes which have been passed down from common ancestors. If one of these genes contains a mutation which causes a disease, genetic disorders like Gaucher may become more prominent in that particular population.

What is currently known about the causes of Gaucher disease and what further research needs to be performed to understand the underlying mechanism of the condition?

There are several studies currently being conducted to help understand the natural course of Gaucher disease, as well as how to help people better understand and manage their condition.

At this stage, we know the disease is caused by one or more genetic mutations. We also know that a person must have two copies of the defective gene (one from each parent) in order to develop symptoms.

The mutation causes a defect in the activity or function of an enzyme called glucocerebrosidase, which, in turn, causes a fatty substance called glucocerebroside to collect in cells. These “Gaucher cells” then accumulate in and affect tissues and organs.

At the moment, researchers are trying to better understand the large variance that occurs between phenotype (our observable traits) and genotype (our genetic make-up). Many studies have looked at the link between specific mutations and clinical aspects of the condition, but no firm link has yet been found.

Researchers are also trying to understand why there are so many different clinical presentations of Gaucher disease. In terms of severity for example, some people have mild symptoms while others have moderate or severe symptoms, despite these people all sharing the same genetic mutation.

Understanding is also limited regarding the observed higher incidence of other diseases that are associated with Gaucher disease, such as Parkinson's and multiple myeloma. Patients are more prone to developing these other diseases when they are affected by Gaucher disease and studies are being conducted to try and find out why this is the case.

How long does it typically take to diagnose Gaucher disease and why is the condition often misdiagnosed?

Like most rare diseases, the relatively common symptoms of Gaucher disease, such as fatigue and shortness of breath, can often mean this rare condition goes undiagnosed. For some patients, it can take up to ten years for an accurate diagnosis to be made.

Typically, more than half of type 1 patients are diagnosed during childhood, and the vast majority of Gaucher patients (more than 80%) are diagnosed before the age of 30.

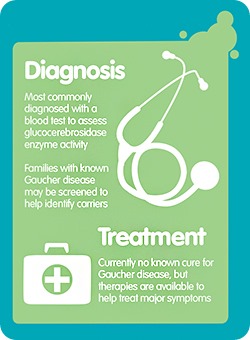

Gaucher disease is diagnosed by assessing the activity of the glucocerebrosidase enzyme using blood or skin cells. Genotyping can then be used to confirm the diagnosis by checking for the presence of specific mutations associated with the disease.

However, currently, there are no national screening programs in place, which often means people are not diagnosed until their condition becomes severe. Screening is available for vulnerable populations such as Ashkenazi Jews or families with a known history of Gaucher disease. Diagnosing Gaucher disease early may improve patients’ lives and make it easier to manage disease progression.

Why is raising awareness of Gaucher disease so important?

Raising awareness would help to build recognition of Gaucher disease, and other rare diseases, among the general population and healthcare professionals, which may improve understanding of the conditions and their associated symptoms.

A patient may only have mild symptoms initially and these can take years to become severe, which often means many of these patients do not seek medical attention at first. For example, patients may not go to a physician because they are experiencing fatigue, and then one day they start to experience severe pain because their liver or spleen has enlarged. By that time, managing the disease may become more difficult.

It is therefore important to learn about the natural course of the disease, so we can better understand how the condition progresses, and how to perform accurate diagnosis in the very early stages of the disease.

This is particularly relevant to the general population because physicians will often be aware of how prevalent the disease is among Ashkenazi Jews, for example, and will therefore be more mindful of checking for the disease among these individuals than in the general population.

Please can you outline some of the initiatives Shire is working on to provide support to patients?

Shire recognizes that for patients with life-altering conditions such as Gaucher disease, specialized services and support are required. One support service we offer is a program to help patients share their experiences of living with Gaucher disease, and connect with others who are facing the daily challenges of the disease. This program is now well established in the U.S and will be rolling out in Europe this autumn.

We also offer a patient support service in some countries, which provides patients and their families with comprehensive product support tailored to the individual’s needs.

What do you think the future holds for Gaucher disease?

For patients with Gaucher disease, efforts are currently focused on providing a better quality of life. But in the future, more studies on the natural history and genetic aspects of the disease are needed, as well as research into potential treatment options.

I think the more we understand about what is happening at the genetic level, the better position we will be in to find potential future molecules that could be used to treat the condition.

What are Shire’s plans with regards to Gaucher disease going forwards?

Shire continues to invest in capacity and technology to ensure patients receive life-altering treatment to manage their condition. That is extremely important for us.

Shire continues to invest in capacity and technology to ensure patients receive life-altering treatment to manage their condition. That is extremely important for us.

We will also continue to study the clinical course of the Gaucher patient population through data that are collected in our longterm international disease registry, the Gaucher Outcome Survey. This data helps to evaluate patients’ response to treatment and assess any commonalities that patients share in the course of their disease with the aim of helping patients and physicians better understand and manage symptoms of Gaucher’s disease.

Where can readers find more information?

• European Gaucher Alliance (EGA)

• Focus on Gaucher

About Dr. Olivier

Dr. Olivier is the Global Medical Lead for Gaucher Disease in Shire’s Rare Diseases Business Unit. He joined Shire in 2011 and has over 13 years of global medical affairs experience across a variety of specialised disease areas and pharmacogenomics.

Dr. Olivier is the Global Medical Lead for Gaucher Disease in Shire’s Rare Diseases Business Unit. He joined Shire in 2011 and has over 13 years of global medical affairs experience across a variety of specialised disease areas and pharmacogenomics.

Prior to joining the pharmaceutical industry, Dr. Olivier worked in HIV/AIDS clinical research and practice, and was a practicing physician in Canada and Africa. Dr. Olivier has an MD from Laval University, Quebec City, Canada, and trained in tropical diseases and as a general practitioner.