The ‘two week wait’ referral was brought into England in 2000. If a patient goes to see their GP and they meet specific criteria that cause the GP to think they might have cancer, then they should be referred to see a specialist within two weeks.

The majority of ‘two week wait’ referral patients don’t turn out to have cancer. The emergency route refers to patients who are referred via A&E or through an emergency GP referral or transfer from another hospital.

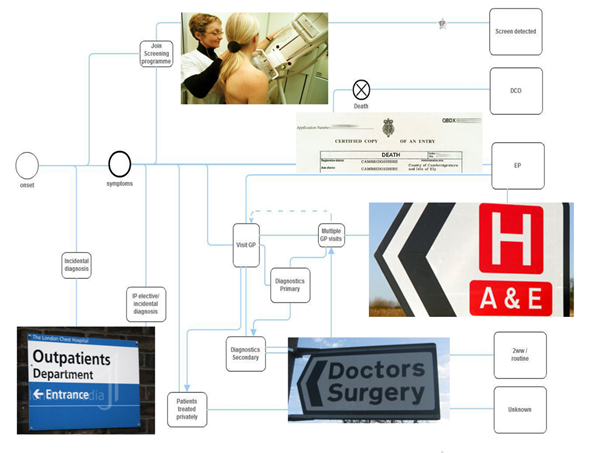

Based on the original 2006 to 2008 data: Green - 5% diagnosed through screening; Light blue - 24% diagnosed through emergency presentation; Dark blue - 71% diagnosed through other routes

How do the chances of survival compare for these routes?

Across the board, emergency referrals have much poorer chances of survival than ‘two week wait’ referrals. This does however vary by cancer type.

For breast cancer, over half of women are now diagnosed via two week wait referrals, they have very good one year survival rates of 97%. In contrast, less than 5% are emergency referrals, of which more than 50% die within one year.

There are also variations depending on age, sex and deprivation.

According to the latest Routes to Diagnosis data, what proportion of patients are diagnosed by these routes in England and how does this compare to previous figures?

Previous figures for 2006 showed just under a quarter of patients (24%) were diagnosed as an emergency and a quarter (25%) were diagnosed by the two week wait route.

By 2013, the emergency route had dropped to 20% and the two week wait had increased to 34%. These results do however hide some big variations for certain cancers.

What do you think are the reasons for this positive trend?

I think there are quite a few. Since 2009, there's been an increased focus in England on early diagnosis, with many national and local initiatives introduced to target and try to make improvements in early diagnosis, including the Be Clear on Cancer campaigns.

Public Health England leads this campaign program with partner organizations, which aim to and do successfully increase awareness amongst patients and the public about cancer signs and symptoms, so that people present earlier to the GP when they see something is wrong and the GP can then act on that and refer someone for tests more quickly.

The number of people who are referred on the ‘two week wait’ pathway has been increasing year after year and this continues to increase.

GPs are using this pathway more and more and there are also tools that have been developed to help GPs in their decision making. These decision support tools can be used by the GP to make an earlier referral for people with a certain combination of cancer symptoms or red flag symptoms.

There are various things that we've tried to introduce across the country that give people support to act on things that they notice aren't quite right.

There are also screening programs and we've seen the introduction of the National Bowel Screening Program, which has had a positive effect on this trend and, of course, the breast and cervical screening programs are playing their part.

How does cancer diagnosis in England compare to other countries?

It's been repeatedly shown that cancer survival in England and the UK in general, is poorer than the best in Europe and this was shown in the press again last week.

Studies suggest that the difference is largely down to the fact that cancers in the UK are diagnosed at a much more advanced stage than in other countries and when someone is diagnosed at a later stage, they've then got a much poorer chance of being cured and therefore surviving.

There's an international program called The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership, which has shown in a number of studies that the survival of cancer patients in England is poorer compared to other jurisdictions, particularly in the first year after diagnosis and for patients aged over 65. We therefore have a particular problem with older patients and with diagnosing patients late.

Why does emergency presentation still remain high for some cancers, like liver and pancreas?

Despite the improvements that we have seen for all cancers, we actually have a high emergency presentation rate for many cancers. For the ones you've mentioned, 39% of patients with liver cancer and 45% of those with pancreatic cancer still present through emergency routes.

There are a number of factors behind this, but we think the main problems are that these cancers don't always exhibit easy to spot symptoms at an early stage, and patients who do have symptoms that are easy to spot tend to attribute them to other causes.

For example, common symptoms of both those cancers include stomach and back pain and weight loss, all of which are very easy to put down to something else. Jaundice is another sign, but a patient might not recognize jaundice and might not act on that, so there's inevitably a delay in going to the GP.

There will also be inequalities and variations in terms of people noticing symptoms and going to the GP and we need more research to understand why certain people may react more slowly to some of these symptoms. That's going to be one of the big areas for future work. But if the cancer itself doesn't show symptoms until it’s too late, then people will present with an emergency and the outcomes will be poorer.

What needs to be done to improve England’s cancer survival and patients’ experience further?

This is obviously an area of great interest in England and we've recently had an independent cancer task force that has drawn up a report looking at where we need to be going in the next five years and beyond. Today, there are some areas where we think we can make quite a big difference across the whole of the patient pathway.

Looking at the pathway, we want to increase the focus on prevention. Further reductions in smoking and obesity will make a big difference to the number of people being diagnosed in the first place.

Of course, diagnosing patients earlier is a big focus for me with the Routes to Diagnosis study, but that means we need more diagnostic capacity. We need to look at new models of care so that patients are seen and cared for in the right settings and have the right access to tests and results.

We also need to look at patient experience and improve the way we communicate with patients and ensure that patient care is joined up across all the organizations, not just within the hospital. The time a patient spends in hospital with cancer is only going to make up a small part of their overall cancer experience and journey.

We need to make sure that we're using all our latest modern equipment, drugs and technology to treat people effectively and efficiently and we need to look at commissioning across the care pathway. We need to not just look at hospital care, primary care or end of life care, but the whole care pathway and make sure that we are being efficient and joined up across those.

Amongst all of those things, one area that interests me the most is the need to make sure that we can measure the improvements that are occurring, so we know what's working and what isn't. There's no point putting measures in place if we can't count the patients that are being affected by them and see how their experience and outcomes have changed over time and whether something isn't working, in which case we need to stop doing it and do something else.

What do you think the future holds for cancer diagnosis in England?

More patients are going to be diagnosed and more patients are living with cancer. We have an increasingly aging population, with people living longer, more people getting cancer, and because we're generally keeping people alive a bit longer, more people will develop cancer.

There's a lot that the future holds for England. The NHS needs to evolve to deal with the additional demand, but also we need to look at the longer term consequences for services and for patients who are themselves living with cancer as a long term disease. Increasingly, cancer is not killing them as quickly and we therefore need to work out what that means for people and families.

I think we are also going to see an increase in the use of molecular diagnostic tests to treat and diagnose cancer. For example, an initiative called the NHS 100,000 Genomes Project is sequencing genomes from 25,000 cancer patients, which will lead to personalized medicine and diagnostics. That's really cutting edge stuff that will change how we diagnose and treat people.

One thing that the Routes to Diagnosis study, in particular, illustrates and that the things I've said earlier illustrate is the unacceptable variation that exists in access to care across different areas, population subgroups and cancer types.

We need to make sure that our research doesn't widen the gap between the rich and the poor or the old and the young, for example, but actually enables us to close the gap in the future. That's going to be a really big challenge.

Where can readers find more information?

Our publication is on our website and the original research was published in the British Journal of Cancer a few years ago.

Also, we'll soon be making lots more reports available. We've got full results coming out in about a month or hopefully less, and then we'll be producing 49 site specific reports looking at each cancer in detail, so that people will have a report on pancreatic cancer or on liver cancer, for example. We're trying to give as much information out as possible.

We have lots of charity partners that also use the data. Cancer Research UK uses a lot of the Routes to Diagnosis data and they've recently published a blog, which is really helpful. They also do clear infographics and try to translate what we've found into more user friendly, public facing information.

Target Ovarian Cancer has also used the data in one of their recent news stories. We do try and work with partners and charities in particular, to get the message out there and get the information targeted where people can actually make a difference and do something with it.

About Lucy Elliss-Brookes

Lucy Elliss-Brookes is the Deputy Head for National Cancer Analysis at the National Cancer Intelligence Network in Public Health England. She has worked in cancer intelligence for seventeen years, progressing from a solid cancer analytical background to information management and senior national leadership positions. Lucy currently leads a team of highly skilled cancer analysts and managers responsible for measuring cancer outcomes across England and the UK and supporting national public health and healthcare policies aimed at reducing mortality from cancer.

One of her most significant achievements has been the creation and development of the Routes to Diagnosis study – a big data project that algorithmically links data from different sources (including cancer registration, hospital episode statistics, cancer waiting times and NHS screening programmes) to assign patients to different healthcare pathways to a cancer diagnosis. Ground breaking for its evolving policy and research implications, particularly in the early diagnosis field, this project remains unsurpassed internationally (no other comparable population-based resource exists in any other country or healthcare system thus far).

Lucy is passionate about population health improvement based cancer data, information and intelligence. She has presented nationally and internationally on many aspects of her work, with a focus on demonstrating the positive impact that cancer intelligence can have on patient care. She is also enabling and supporting a range of cancer epidemiology projects involving Public Health England analysis staff and academic partners.