Charles Bonnet syndrome is the name we give to the visual hallucinations associated with eye disease. There are lots of different causes of visual hallucinations. Many different medical problems and medications can cause them, but, when the cause is eye disease, it's referred to as Charles Bonnet Syndrome after Charles Bonnet, who was a natural philosopher in the 18th century.

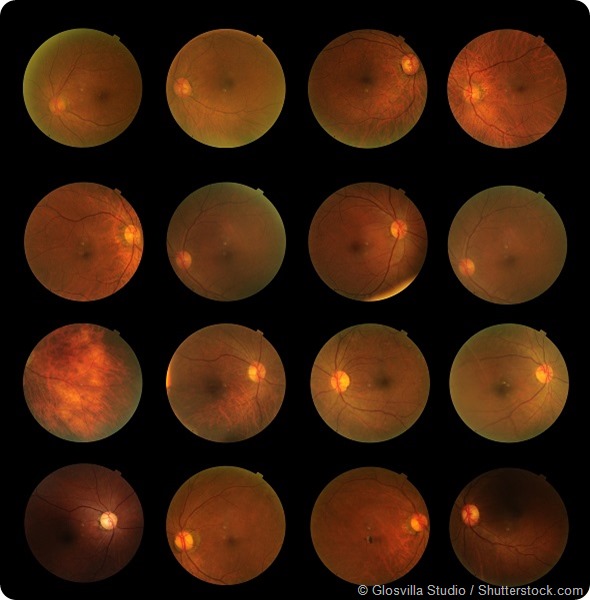

The condition can occur as a result of any eye problem, including cataracts, diabetic retinal problems and glaucoma. In the UK, it is most commonly associated with macular degeneration, but only because that is the most common eye disease in the UK.

There needs to be a moderate loss of vision for Charles Bonnet Syndrome to occur, which would be about half way down the chart at the optician’s. If you've got that level of visual problem, then you are at risk of developing Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

What do the CBS images look like? Do they tend to be unpleasant?

The hallucinations range from very simple dots, colored blobs, sparkles of light and Catherine wheels through to more formed images such as a brick wall, a geometrical pattern or a disembodied face that may loom up in front of you and be distorted, often with prominent or twisted features. People describe the latter as being similar to gargoyles or grotesque in some way.

People may also see figures that are usually in some form of elaborate costume such as a Napoleonic uniform, a knight’s shining armor, or a Victorian or Edwardian costume. The figures are also often wearing some form of head gear such as a hat, bonnet or an aristocratic wig.

Text and strings of letters are also commonly seen. These may look like words initially but, when looked at more carefully, the letters may not be real or they may be real but don't form words that make any sense so they can't be read. This also happens with musical notes. People may see crotchets and quavers, but those people who can understand music say that they can't actually read the music.

The list goes on, but those are the most common types of hallucination.

With regards to their unpleasant nature, only about a third of people find Charles Bonnet Syndrome distressing. That doesn't necessarily mean that what they see upsets them; it may be more that they find the whole idea of having hallucinations upsetting. About two thirds of people don’t mind having hallucinations, while around 10% of people actually positively enjoy them because it reminds them of what it was like to see before they developed eye disease.

In fact, Charles Bonnet said that his grandfather, Charles Lullin, enjoyed the hallucinations and used to chat about them. We've therefore inherited this idea that Charles Bonnet Syndrome is something that's enjoyable and pleasant, even though this is only true for a very small minority of people.

Is it known why the images tend to be vivid and detailed?

That's an important question to ask. It makes us consider what a hallucination actually is. When a hallucination occurs, it has the same vivid visual qualities that real things around you have. That's distinct from imagery, which is something we conjure up in our own mind's eye, inside our heads. Some people have very vivid images, but they're nothing like hallucinations. It’s the vivid nature of a hallucination and the fact that it feels like you are looking at something in the world around you, not in your mind’s eye, that helps distinguish a hallucination from visual imagery.

In fact, you can't tell whether what you're seeing is a hallucination or real, based just on the quality of what you're seeing. You can work out that it can't be real because you know there can't be a figure in Edwardian costume in your room, for example, or you may reach out and try to touch the figure, only to find it's not there. However, you can't tell that the figure is any different to a real person being in front of you, just by looking at it.

Hallucinations are perceptual experiences; the same thing is going on in your brain when you're having a hallucination as when you're seeing a real face or figure. The only difference is that in the case of hallucination, it's not triggered by something that's actually in front of you. It's instead spontaneously triggered by activity within the brain.

How can CBS be distinguished from hallucinations caused by psychiatric problems?

In Charles Bonnet Syndrome, you may not necessarily immediately realize that something is a hallucination because it looks so real, but you can learn to understand that it is a trick of the mind and that what you are seeing isn't really there. With time, people with Charles Bonnet Syndrome learn to become familiar with the types of hallucinations they get and, when they occur, recognize them as such.

That is not necessarily the case in other disorders where visual hallucinations occur, such as psychiatric problems and dementia. Someone with dementia may be unable to understand that what they are seeing isn’t real, or may respond to reassurance when they are told it is a hallucination, but forget this when the hallucination reoccurs. Someone with dementia may also start to develop strange, false beliefs (delusions) about what is causing the phenomena. For example, they may think that because they're seeing a young child in front of them, that the neighbor’s child has got the key to the house, has let themselves in and is sitting in front of them. These delusions don't occur in Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

The way people respond to and understand hallucinations is an important difference between Charles Bonnet Syndrome and other conditions. There are also differences in the types of things people hallucinate. In Charles Bonnet Syndrome, you almost invariably have simple hallucinations of colors, lines and dots, and geometric patterns like brickwork. These simple hallucinations never occur in Alzheimer's disease or other dementias.

Another difference is the figures seen. In Charles Bonnet Syndrome figures tend to be strangers in bizarre, elaborate costume. In dementia and other conditions such as Parkinson's disease, people see someone they know. They may see an uncle, aunt, grandfather, or spouse, for example or somebody else who is familiar to them but they do not have the bizarre costumes seen in Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

Finally, in the dementias and Parkinson's disease, people don't just get visual hallucinations alone. They may hear voices, either at the same time or on other occasions or the figure they see may talk to them. That never happens in Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

By looking at the overall picture and whether someone has delusions or other types of hallucination, you can get a pretty good idea as to whether someone’s hallucinations are being caused by Charles Bonnet Syndrome or one of those other conditions.

How many people with sight loss are thought to be affected by CBS?

Nobody knows the answer to that. We know there are about 500,000 people with macular degeneration in the UK and that between 10 and 60% of those will get Charles Bonnet Syndrome. From that one eye disease alone, we can therefore estimate that there are probably between 50,000 and 300,000 people with Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

However, that's got to be an underestimate for a number of reasons. Firstly, we know that lots of people don't own up to having the problem and, secondly, there are lots of other eye diseases and I've only given you the numbers for macular degeneration. That's probably the one that's going to cause the largest number of cases, but, if you include all the other eye diseases as well, the number is going to be more towards the 300,000 end of the range, or above, and that’s just in the UK alone.

What is currently known about the causes of CBS?

Our brain scanning experiments, which we performed more than fifteen years ago now, have shown what happens in the brain when a person has a Charles Bonnet Syndrome hallucination.

We had people lying in the brain scanner telling us when they started to hallucinate and when they stopped. We then looked at the scans to see what had changed in their brains at the time of the hallucinations. We found that there is a spontaneous increase in brain activity in particular regions of the visual cortex, the part of the brain that deals with vision, at the time of a hallucination and what a person sees in their hallucination depends on where the spontaneous increase occurs.

Within the visual cortex there are specialized areas for the different things we see such as colors, faces and objects, for example. If the spontaneous increase happens to be in cortex specialized for colors, you will suddenly see a color blob in front of you, whereas if it's in the face feature area, you might see a distorted face popping up in front of you.

Why the spontaneous increase in activity occurs at a given time or in a given part of the brain, we don’t yet understand. It may just be down to a chance factor.

The next question is why these spontaneous increases in activity occur at all? The answer to that is that it's the brain’s normal response to vision being lost through eye problems . When you have eye disease, much less information carried by neural signals is travelling from the eye to the brain. The brain responds by becoming more excitable and it's this excitability that causes the spontaneous increases of activity and hence, the hallucinations.

What further research is needed to improve our understanding of CBS?

Paradoxically, the big question at the moment is not why people have hallucinations, but why they don't have hallucinations. There are lots of people with macular degeneration who never develop Charles Bonnet Syndrome and it could be that for every hundred people with macular degeneration, only ten or twenty will start hallucinating. The big research question at the moment is what is different about those people who don’t hallucinate and how do we identify why some people get it and some don't.

At the moment, we are finding that it's something to do with the way the brain is responding to loss of vision after eye disease. You can think about it as the way the brain rewires to compensate for the change in vision and it may be that a certain type of rewiring leads to visual hallucinations. Whether that's caused by genetic factors or some other brain factors, we don't yet understand and is something that we're looking into.

What help is currently available for people with CBS?

There is a range of different approaches to helping people with Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

For people who don’t find the hallucinations distressing, but just don't know what they are or are worried that the hallucinations mean they're developing a serious mental illness or dementia, all you need to do is give them information and educate them about the condition. The Macular Society and the Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) provide resources such as information packs. However, the challenge is getting the information to the people who need it.

A person might start to have Charles Bonnet hallucinations and not know what it is or make a connection between the hallucinations and their eye disease because they’ve never heard about it. Without knowing what to look for on the internet, they cannot find out more about it and may never get access to the information they need. One way to get round the problem is to try and make sure that everyone who is diagnosed with an eye problem, is at least forewarned of the possibility that they may develop the syndrome in the future and that their eye condition may cause visual hallucinations.

Only about a third of people actually need more significant help with the hallucinations and those are the people who find them distressing. For them, a number of support groups are out there, running telephone counseling services, for example, that can help people come to terms with the hallucinations.

Do you have any tips for dealing with hallucinations?

There are various techniques that people can use to stop a hallucination as it occurs. This is not a cure for Charles Bonnet Syndrome, but there are things that you can do when you're having a particularly distressing hallucination such as seeing a face looming in front of you, to stop the hallucination at that point in time. It may come back a few hours later, but at least it can be stopped for that moment, which gives people some control over it.

These sorts of techniques include moving the eyes in a certain way or making yourself more alert. We know that the hallucinations occur when people are in a state of quiet wakefulness, sitting in a chair and maybe listening to the radio or television, for example. If people can get out of that state, then the brain no longer creates a hallucination. That may involve the person getting up and doing something else, talking to someone or trying to occupy themselves in a different way.

Another technique involves changing the lighting. If the hallucination is being triggered by an inadequate amount of light coming into the eye or too much coming in, then in theory, increasing or decreasing the amount of light by switching the lights on or off may help.

People are advised to find what works for them, as no one thing necessarily works for everyone. For people who find the hallucinations very distressing, the final port of call is medication. Various medications are available that have been shown to work, at least in some people. A GP would usually refer people with distressing hallucinations to a specialist who may then start trying some of the medications to help stop the hallucinations.

Where can readers find more information?

About Dr ffytche

Dr ffytche is an academic old age psychiatrist with a special interest in visual perception and its dysfunction. He is a Clinical Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London and Consultant at the Maudsley Hospital, where he runs a specialist clinic for visual perceptual disorders. He has published extensively on clinical and neuroscientific aspects of visual hallucinations and is an international expert on Charles Bonnet Syndrome.