Parasitic worms can live inside humans gaining nourishment from the food we ingest (roundworms) or from our blood (hook worms), whilst being safe from predators. Although roundworm infections are generally symptomless they are not something any of us would choose to have. However, it has recently been found that infection with roundworm increases a woman's fertility.

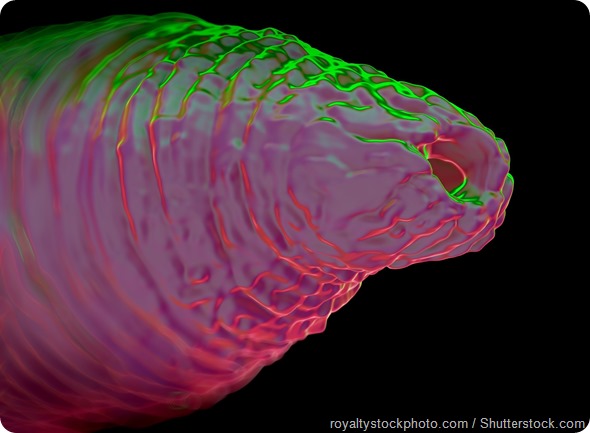

Intestinal worm infections are common, affecting more than 1 billion people, and are particularly prevalent in tropical areas with poor sanitation. The giant roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, is one of the most common and can be 36 cm long.

Despite the repulsion often felt towards parasites, they have a lot in common with a developing human foetus. Both the parasite and the foetus would be deemed by the host to be foreign. Consequently, in order to prevent their destruction, parasites and foetuses need to fool the host's immune system into accepting them.

Indeed, parasites have been shown to trigger some of the same immune changes that occur during pregnancy, eg, stimulating regulatory T cells, which quell immune attacks.

A study was therefore conducted among people living in the Amazon rainforest of Bolivia to investigate the association between intestinal worms and fertility. Researchers analysed data collected from 986 Bolivian women from a forager-horticulturalist settlement over 9 years.

Among this sample 70% of the women were infected with parasitic worms. The infected women in the study were usually unaware they were playing host to the parasites, but those infected with hook worms had a slightly smaller body mass index and lower haemoglobin levels than the other women.

The results indicated that women infected with certain intestinal worms give birth to more children than women who are not. Different types of worm infection were linked with different effects on fertility.

Infection with roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) tended to be associated with earlier first births and shorter intervals between births. In contrast, infection with hookworm was associated with a later first pregnancy and extended intervals between births. A woman infected with Ascaris would bear on average two more children in her lifetime than would a woman free of the parasites.

This sounds counter-intuitive since the worms are stealing nutrients that may otherwise be used by the women. The researchers propose that it a consequence of the Ascaris worms reducing inflammation through their effects on the immune system, which might promote conception and implantation of the embryo in the uterus. Hookworms, in contrast, do not have such an impact on the immune system and any reduction in inflammation would be outweighed by the amount of nutrients they steal.

Reproductive immunologist Norbert Gleicher at The Rockefeller University in New York City explained that the results highlight that “the state of the immune system is of crucial importance to successful reproduction”.

It is unlikely that women will be intentionally infected with Ascaris to improve their fertility, but research into the mechanisms by which the roundworm modulates the immune system may lead to the development of new infertility treatments.

Sources