Our recent research showed that a major source of oxidative stress in muscles of muscular dystrophy (mdx) mice was the enzyme NADPH Oxidase 2 (NOX2). Several studies have shown that statins reduce NOX2 expression and activity in cardiovascular tissues.

Therefore, we postulated that if simvastatin reduced NOX2, as well as targeting inflammation and fibrosis, it would lead to improved muscle health and function in mdx mice.

Please can you outline the pathogenic processes in the functional decline in DMD muscles?

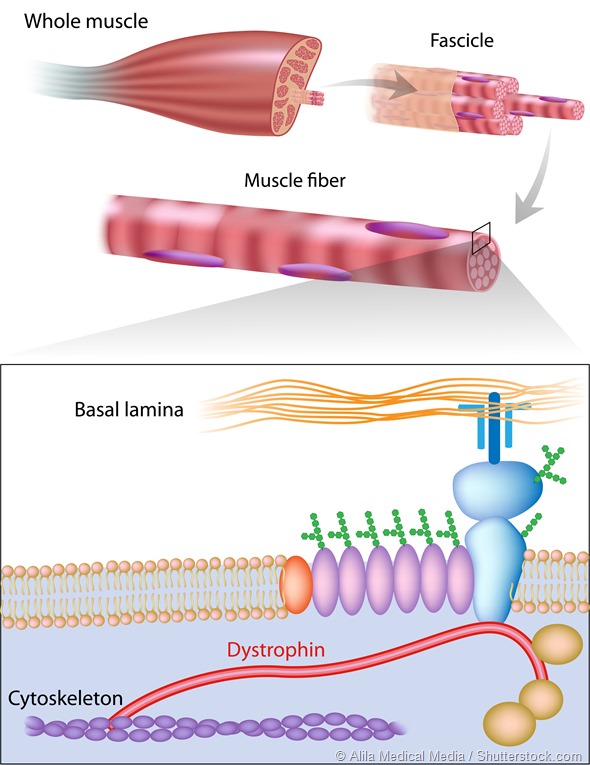

Dr. Whitehead: In DMD muscles, the loss of dystrophin impacts many important signaling and homeostatic cellular functions in muscle fibres. Our research has shown that oxidative stress and increased intracellular calcium entry through membrane ion channels stimulates degradative pathways that lead to muscle damage and cell death.

Muscle fiber structure showing dystrophin location. Dystrophin is commonly mutated in muscular dystrophy diseases.

Normal muscle regenerates effectively following exercise-induced damage, however in DMD, there is a chronic inflammatory response, which impedes regeneration and promotes the progressive replacement of healthy muscle tissue with fibrotic scar tissue.

Together, these pathogenic processes reduce muscle force production, which first causes loss of mobility by the age of 10-15 and eventually weakens the respiratory muscles and heart, leading to death by 20 to 30 years of age.

%20and%20muscle%20from%20Muscular%20Dystrophy%20(right)%20showing%20degeneration%20and%20necrosis%20of%20fibers%20(bluegray%20fibers)-vetpathologist.jpg)

Normal muscle (left) and muscle from Muscular Dystrophy (right) showing degeneration and necrosis of fibers (bluegray fibers).

Why have statins not previously been considered for DMD or other muscular dystrophies?

Dr. Froehner: In a relatively small percentage of cases, statins themselves cause a myopathy. The severity of statin-induced myopathy ranges from muscle pain (often not due to statins, as it turns out) to muscle weakness to a severe necrotizing myopathy. The latter is quite serious but fortunately is very rare.

Furthermore, it usually resolves by stopping statin treatment. Many physicians and some scientists hold the view that statins should not be prescribed for people with any muscle disease.

In fact, this concern has never been tested. As you might guess, we had some difficulty getting our paper published because of this concern.

Can you please outline your recent research in mice? What were the main findings?

Dr. Whitehead: A moderate human dose of simvastatin was administered to mdx mice at different stages of the disease and produced considerable improvements in overall muscle health and physiological function.

Our targeted pathogenic pathways, inflammation, oxidative stress (NOX2 expression) and fibrosis were all significantly reduced by simvastatin. This translated into considerable improvement in muscle function, with a 40% increase in hind limb muscle force and resistance to muscle fatigue.

The diaphragm, which undergoes severe degeneration in mdx mice, also had a significant (20 to 30%) increase in muscle force production in old mdx mice.

Were you surprised by these results?

Dr. Whitehead: Given our hypothesis, we were not surprised by the results, however, we were pleasantly surprised by the large magnitude of improvement provided by simvastatin.

While there is significant interest in dystrophin gene-based therapies for DMD, our results suggest that restoration of dystrophin is not essential for considerable benefits in the overall health and function of dystrophic muscles. Rather, pharmacological agents such as simvastatin could potentially provide an inexpensive, readily available, treatment for DMD.

What further research is needed to back-up these findings?

Dr. Froehner: As Nick said, our published data on simvastatin is very robust. After consulting with several people who have experience in trials, we think a clinical trial in DMD boys is the next step.

In addition, simvastatin has been taken by millions of people, so potential problems are clearly known. Most importantly, simvastatin is already approved for treatment of familial hyperlipidemia in the pediatric population, where clinical studies have shown a good safety profile.

Finally, the cost of the drug is very low. Plans for a clinical trial are now underway.

What do you think the future holds for statins and muscular dystrophy?

Dr. Froehner: That depends on the results of clinical studies. It’s possible that simvastatin could be a treatment on its own, slowing the progression of muscle degeneration. Also, a combination of simvastatin and other drugs currently being tested could be even more effective.

Simvastatin could also benefit genetic correction treatments that are being developed, either by working in concert with gene therapy or exon skipping, or by permitting genetic treatments at an older age. The possibility that simvastatin could at least partially reverse fibrosis could be very important for treatment of older patients.

Do you think statins could be useful in the treatment of any other conditions?

Dr. Froehner: Other muscular dystrophies exhibit fibrosis, oxidative stress and inflammation in skeletal muscle. If simvastatin reduces these pathogenic defects in other muscular dystrophies, it could be used as a treatment in these rare forms of the disease.

What are your further research plans?

Dr Whitehead: We are currently conducting a randomized, blinded, dosing study of simvastatin in mdx mice. From these results we aim to elucidate the most efficacious dose of simvastatin, which we can then translate to our planned clinical trials in DMD. In addition, we are continuing to study the cellular mechanisms that lead to improved muscle health and function in simvastatin treated mdx mice.

Where can readers find more information?

The details of the study are described in our recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

About Dr Stan Froehner

Stan grew up on a farm in south-central Texas and attended the University of Texas at Austin, earning a BS degree in Chemistry. He received a PhD in Biochemistry and Neurophysiology at Caltech and did postdoctoral research at Harvard Medical School.

Stan was a faculty member in Biochemistry at Dartmouth Medical School from 1978 to 1992. He was chair of the Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology at the University of North Carolina for 8 years before moving to Seattle to chair the Department of Physiology & Biophysics at UW Medical School. He is the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Professor of Integrative Biophysics.

Stan’s laboratory has championed the concept that the dystrophin complex serves as a scaffold for signaling proteins. His laboratory discovered the syntrophins, a family of adapter proteins that associate with dystrophin.

The syntrophins direct numerous signaling proteins to the muscle sarcolemma by binding to dystrophin. Disruption of these dystrophin-associated signaling pathways play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of Duchenne and other muscular dystrophies.

Furthermore, these defective pathways are promising targets for drugs that ameliorate the muscle degeneration that defines Duchenne and other muscular dystrophies.

About Dr Nick Whitehead

Nick has studied skeletal muscle physiology for over 15 years. During his PhD at Monash University, Australia, under the supervision of Uwe Proske and David Morgan, he investigated the mechanisms leading to muscle damage and soreness caused by unaccustomed eccentric contractions. This research led to several publications that highlighted the importance of muscle length and passive mechanical properties in the damage process.

He then moved to the University of Sydney in 2002 for postdoctoral studies with David Allen. Here, he studied the mechanisms causing muscle damage in the mdx mouse model of DMD. At the time, dystrophin was widely considered to be a mechanical, ‘shock-absorber’ protein, which protected the membrane from tears during contractions.

A key finding of Nick’s research was that the membrane permeability in mdx mice was largely due to pathways initiated by calcium influx through ion channels and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and not due to mechanical tearing of the membrane. These results highlighted the important signaling role of the dystrophin complex.

A follow up study, partly conducted in Stan Froehner’s lab, showed that NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) was the major source of oxidative stress in mdx muscle. This result provided a new therapeutic target for DMD and was a major catalyst for initiating the experiments with simvastatin in mdx mice.