New research shows that keyhole surgery or minimally invasive laparoscopic robotic surgery could be dangerous in the long run for women with cervical cancer. Unlike open surgeries, minimally invasive surgeries are being increasingly conducted and preferred because of their minimal tissue damage, minimal pain and risk as well as faster recovery. Both studies have been published in the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers however found that women who were undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomies including some that use robotic surgery for example with the Da Vinci device, are at a greater risk of their cancers coming back compared to women who have had an open surgery.

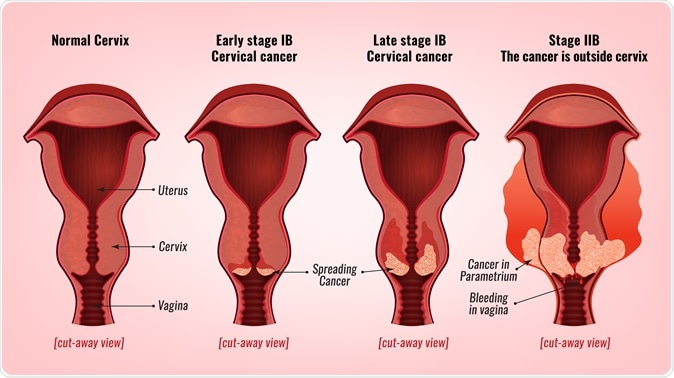

Cervical cancer development. Image Credit: Double Brain / Shutterstock

One of the studies came from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center that has already stopped minimally invasive hysterectomies for women with cervical cancer. Dr. Joe-Alejandro Rauh-Hain, a gynecologic cancer specialist at MD Anderson and a co-author to one of the studies says that the team was surprised with the results of the study. He said that they had expected survival rates for both kinds of surgeries to be around the same.

Due to the drastically reduced risk of bleeding, pain, infections and surgical complications with keyhole surgeries, they are increasingly being preferred in the US. Rauh-Hain said that after these two studies, the surgeons can no longer recommend minimally invasive surgeries to patients with early stage cervical cancer.

Dr. Alexander Melamed of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School was another co-author of the study. He said that personally he would now refrain from offering “minimally invasive radical hysterectomy” in cervical cancer patients until more research shows that the risks are absent.

This first study looked at 2,461 women who were diagnosed with stage 1 cervical cancer between 2010 and 2013. Around half of these women (1225) underwent minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy while the other got open surgeries. Of the women who underwent keyhole surgeries, 79 percent had be operated using robotic assistance. Authors wrote, “Over a median follow-up of 45 months, the four-year mortality was 9.1 percent among women who underwent minimally invasive surgery and 5.3 percent among those who underwent open surgery.” Women undergoing minimally invasive surgeries were 65 percent more likely to die within the four years following the operation compared. In comparison to 70 women who died within four years after surgery after an open surgery, 94 women undergoing minimally invasive surgery died during the same period.

In the second study the researchers randomly assigned 631 women to undergo either open surgery or minimally invasive hysterectomy. These procedures were conducted at 33 hospitals across United States, Brazil, Columbia, Italy, Peru, Australia, Mexico and China. At 4.5 years post-surgery, 95 percent women undergoing traditional open surgeries were disease free compared to 86 percent women undergoing minimally invasive surgery.

Dr. Pedro Ramirez, a professor in gynecologic oncology at MD Anderson and one of the researchers on the study explained that for minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, usually carbon dioxide gas is used to inflate the abdomen to visualize the surgical field. He said that this carbon dioxide gas could play a role in causing the cancer cells to be implanted in different parts of the abdominal cavity while operating.

Dr. Shohreh Shahabi, chief of gynecological oncology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine was one of the researchers on one of the study teams. He emphasized that these findings are true for cervical cancers alone as of now and there are several other cancers that are being surgically treated using laparoscopic and minimally invasive surgeries.

Dr. Amanda N. Fader, director of the Kelly Gynecologic-Oncology Service at Johns Hopkins University wrote an editorial accompanying the studies saying that these results were a “great blow” to minimally invasive surgical approaches for cervical cancer. She said Johns Hopkins has since this stopped keyhole surgeries for cervical cancers and reverted back to open surgeries.