Nov 15 2018

Pancreatic cancer death rates in the European Union (EU) have increased by 5% between 1990 and 2016, a report launched today reveals. This is the highest increase in any of the EU’s top five cancer killers which, as well as pancreatic cancer, includes lung, colorectal, breast and prostate cancer.

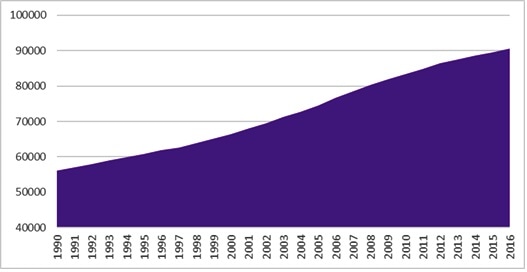

Number of Pancreatic Cancer Deaths in EU (1990-2016)

‘Pancreatic Cancer Across Europe’, published by United European Gastroenterology (UEG) to coincide with World Pancreatic Cancer Day, examines the past and current state of pancreatic cancer care and treatment, as well as the future prospects, such as targeting the microbiome, for improving the prognosis for patients. Whilst lung, breast and colorectal cancer have seen significant reductions in death rates since 1990, deaths from pancreatic cancer continue to rise. Experts also believe that pancreatic cancer has now overtaken breast cancer as the third leading cause of death from cancer in the EU.

% Change in Pancreatic Cancer Death Rates Across EU28 (1990-2016)

| Cancer Site |

1990 Death Rate |

2016 Death Rate |

% Change Between 1990 and 2016 |

| Breast cancer |

14.82 |

11.11 |

-25% |

| Tracheal, bronchial and lung cancer |

37.77 |

30.30 |

-20% |

| Colorectal cancer |

21.80 |

18.72 |

-14% |

| Prostate cancer |

8.74 |

8.83 |

+1% |

| Pancreatic cancer |

9.30 |

9.72 |

+5% |

Pancreatic cancer has the lowest survival of all cancers in Europe. Now responsible for over 95,000 EU deaths every year, the median survival time at the point of diagnosis is just 4.6 months, with patients losing 98% of their healthy life expectancy. Often referred to as ‘the silent killer’, symptoms can be hard to identify, thus making it difficult to diagnose the disease early which is essential for life-saving surgery.

Despite the rise in death rates and dreadfully low survival rates, pancreatic cancer receives less than 2% of all cancer research funding in Europe. Markus Peck, UEG expert, explains:

If we are to take a stand against the continent’s deadliest cancer, we must address the insufficient research funding; that is where the European Union can lead the way. Whilst medical and scientific innovations have positively changed the prospects for many cancer patients, those diagnosed with pancreatic cancer have not been blessed with much clinically meaningful progress. To deliver earlier diagnoses and improved treatments we need to engage now in more basic as well as applied research to see real progress for our patients in the years to come.”

Microbiome – the key to turning the tide?

After forty years of limited progress in pancreatic cancer research, experts claim that new treatment options could finally be on the horizon as researchers investigate how changing the pancreas’ microbiome may help to slow tumour growth and enable the body to develop its own ‘defence mechanism’. The microbial population of a cancerous pancreas has been found to be approximately 1,000 times larger than that of a non-cancerous pancreas and research has shown that removing bacteria from the gut and pancreas slowed cancer growth and ‘reprogrammed’ immune cells to react against cancer cells.

This development could lead to significant changes in clinical practice as removing bacterial species could improve the efficacy of chemotherapy or immunotherapy, offering hope that clinicians will finally be able to slow tumor growth, alter metastatic behavior and ultimately change the disease’s progression.

Professor Thomas Seufferlein, pancreatic cancer expert, comments:

Research looking at the impact of the microbiome on pancreatic cancer is a particularly exciting new area, as the pancreas was previously thought of as a sterile organ. Such research will also improve our understanding of the microenvironment in a metastatic setting and how the tumor responds to its environment. This will inform the metastatic behavior and ultimately alter disease progression.”

“With continued investment in pancreatic cancer research, we should have new, important findings within the next five years and, hopefully, find that targeting the microbiome as well as tumour cells will significantly improve treatment outcomes and reduce death rates”, adds Professor Seufferlein.