Researchers have found that bowel cancer cells have a mechanism by which they can switch off some key molecules on their surfaces and thus escape being recognised and killed by the immunotherapy agents.

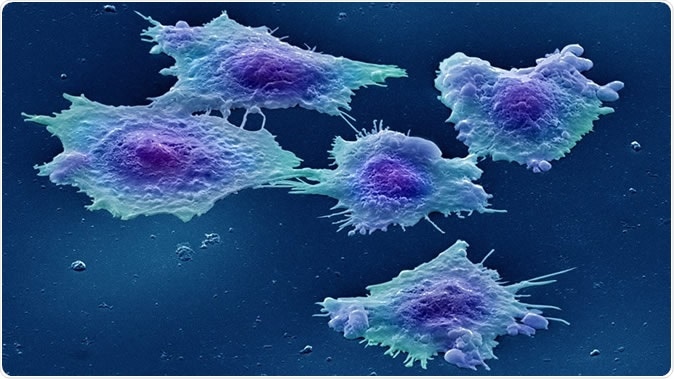

Image: Colour-enhanced image of human colon cancer cells in culture. Credit: Annie Cavanagh. License: (CC BY 4.0)

Researchers from the Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust explain that cancer cells can literally “change their spots” so that they are unrecognizable to the immunotherapy agents. They can do this by switching off the key molecules on their surfaces that the immunotherapy agents are trained to recognize.

The team tested samples of bowel cancer cells and found that while some responded well to immunotherapy, others failed to do so. They tested the changes in these tumour cells by examining miniature tumours grown in the labs. The team then tried a combination of available agents to reverse the efficacy of the immunotherapy agents so that they could work for more patients.

The researchers explain that the antibody-based drug cibisatamab – an immunotherapy agent, could work better in more patients if the theory is proved. This study, they add, could also help determine which of the patients would respond well to immunotherapy and which of them would not.

Cibisatamab is one of the new and promising immunotherapy agents that can help identify the cancer cells using immune mechanisms and then kill them selectively. However some patients respond well to this drug while others respond poorly or not at all. Researchers explain that one arm of the drug attaches itself to a molecule present on the surface of the cancer cell. It is called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The other arm of the drug activates a special immune cell called a T cell that can attack and kill the tumour cell. When grown in the labs the team found that some of the tumour cells could hide themselves from treatment by changing their surface molecules and the CEA levels thus reduce.

Cibisatamab has been found to be effective against most bowel cancer patients. This study aimed to look at the cause of its non-efficacy in some of the patients. Biopsy samples were taken from eight bowel cancer patients for this study and mini replicas of the tumours were created in the labs of ICR. Some of the cells contained high numbers of CEA, some low and some were in between, explain the researchers. The team then used cibisatamab to treat these patients and saw that 96 percent of those with high CEA responded well with the drug and only 20 percent with low CEA responded to the drug. They noted that 53 percent of those with mixed levels of CEA responded to the drug.

As a next step the team allowed the cancer cells to grow again in the lab for a month. They noticed that the CEA levels had changed in these regrown tumours. This meant that the cells could change their CEA so as to escape being recognized by the immunotherapy agent. The researchers delved deeper into the genetic make-up of the cells with low CEA on their surfaces and found that these cells have an increase in the WNT pathway of genes. Certain drugs target this pathway in the cancer cells. They realized that if these drugs were combined with cibisatamab, the efficacy of the cibisatamab could be improved in the cancer cells. WNT pathway targeting drugs include tankyrase inhibitors and porcupine inhibitors. They found that when these drugs were used the CEA levels on the cells were increased. This made them vulnerable to the immunotherapy, explained the researchers.

Dr Marco Gerlinger, Team Leader in Translational Oncogenomics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Consultant Oncologist at The Royal Marsden said in a statement, “Cancer is very good at hiding from the body's immune system. The latest successful immunotherapies work by acting as a matchmaker to bring the immune system together with cancer, so that it can see it and attack it.” He explained, “Our study has found that bowel cancers have a way of dodging even the newest of immunotherapies - changing their spots by altering the levels of a key molecule on the surface of cells, so that they become harder to recognise. We used a new technique for growing miniature replicas of tumours to develop a way of testing whether patients will respond to immunotherapy. And best of all, we were able to identify an existing inhibitor of the WNT pathway which could be used to reverse this process. We hope that this could in future help immunotherapies work in more patients, by making cancer cells more visible to immune cells.” He was the study leader.

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, added, “As we move away from one-size-fits-all therapy for cancer, it's so important that we are able to identify which patients are most likely to respond to a drug, and do everything we can to avoid resistance to treatment for as long as possible. This research reveals a way in which cancers are able to hide from a promising new type of immunotherapy. Although the work is still in its early stages, it could be used to develop a test for who is most likely to respond to the drug, and points to possible drug combinations that might prevent or delay resistance.”

The study was funded by the Cancer Research UK and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer research (ICR) and The Royal Marsden.