Cannabis, or marijuana, is the most commonly used recreational drug that has several psychoactive properties. In addition to recreational uses to achieve a ‘high’, cannabis also has many proven and presumed medicinal properties, as well as being used for religious and spiritual purposes.

Image Credit: Dmytro Tyshchenko/Shutterstock.com

Cannabis is the most widely used illegal drug, as it considered illegal by a majority of countries except Uruguay, Canada, Georgia, South Africa, 11 US states plus D.C (though federally still illegal). However, several countries have now allowed the use of medicinal cannabis with the approval of a licensed doctor.

The Neurobiology of Cannabis

The key compound within cannabis that causes a ‘high’ is called tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, one of 66 cannabinoids, including cannabidiol (CBD) – which is used as a medicinal product.

THC is rapidly absorbed with bioavailability depending on the duration of inhalation and depth of volume inhaled, as well as the duration breath is held. Cannabinoids are lipid-soluble and can remain in fatty tissues for a prolonged period and THC can be found in the body weeks after even a single administration.

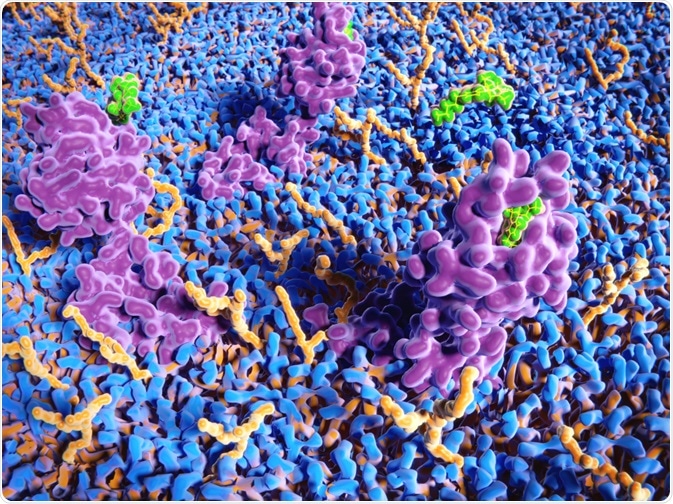

THC binds to two types of cannabinoid receptors in the body: CB1 receptor and CB2 receptor. CB receptors are metabotropic G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and the CB1 receptor is found primarily within the central nervous system (CNS) whereas CB2 receptors are found predominantly in peripheral tissues.

The psychoactive effects of cannabis are primarily mediated through THC biding to CB1 receptors within the CNS.

Endogenous (bodily produced) cannabinoids, known as endocannabinoids, naturally activate CB1 receptors within the brain and play a key role in reward, cognition, appetite, and analgesia (pain relief).

THC can also indirectly lead to dopamine release that leads to the desired euphoric psychoactive effects but also lead to dependence and addiction over chronic use.

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com

Brain Differences in Cannabis Users

Before discussing differences between the brains of cannabis and non-cannabis users, it is important to separate the confirmed and presumed protective and beneficial effects of CBD compared to that of the ill-effects of THC.

Since CBD oil has THC separated from it, it is classed as a completely separate medicinal product. Here, the overall effect of recreational cannabis usage (smoking the plant) which also contains THC amongst other cannabinoids and carcinogens will be discussed.

A study published in the Journal of Neuroscience by Orr and colleagues found grey matter volumetric differences with even the most modest use of cannabis in adolescence. 46 14-year old males and females with just 1 or 2 instances of cannabis use underwent voxel-based morphometry (MRI scans) comparing grey matter volumes.

Orr and colleagues found extensive regions of the medial temporal lobes, posterior cingulate, and cerebellum that showed greater grey matter volume in these adolescent low-users of cannabis.

These brain differences may allude to a greater risk of generalized anxiety symptoms in cannabis users.

This study, therefore, highlights that there are key brain volume changes in even the most modest recreational users of cannabis that could predispose individuals to a greater susceptibility to anxiety in the future.

A study published in 2019 by Zhou et al also used MRI scans to examine the function of the brain in 38 heavy cannabis users (+ 44 non-users). All cannabis users irrespective of dependency showed increased ventral striatal reactivity and striatal frontal coupling in response to drug cues.

Those that were dependent showed increased dorsal striatal function and a decreased striatal limbic coupling. These findings show that heavy-users show exaggerated responses in reward pathways in the brain to potentially promote excessive drug use (a vicious cycle).

Concerning presumed associations between long-term cannabis use and impaired executive functioning, and IQ, there are very limited associations and evidence is often contradictory.

However, where there are associations, it is most likely due to heavy and routine daily usage that correlates with reduced executive function and IQ.

Rodent studies have shown a reduced inhibition control when administered with THC routinely and may be related to the structural changes as described previously, or adaptations to the endocannabinoid system – that could lead to binging behavior.

Furthermore, early-adolescent exposure may be more harmful in the long-term outlook than later adolescence, reflecting the different neurodevelopmental stages – and many studies have not accounted for this.

In summary, regular cannabis users display key structural and functional brain differences; even after very moderate use – that may predispose users to continued usage, generalized anxiety, and impairments to executive function and inhibition control.

However, some of the evidence is contradictory or does not support such strong associations. Where there are differences, it may be reflective of regular/routine usage. It is also important to separate studies from early adolescence to late adolescence due to different developmental stages.

Abstinence may be beneficial for a long-term outlook. However, much more research is needed to understand some of the described changes as well as to make more definitive conclusions.

Sources:

- Elkashef et al, 2008. Marijuana Neurobiology and Treatment. Subst Abus. 29(3): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897070802218166

- Zhou et al, 2019. Cue Reactivity in the Ventral Striatum Characterizes Heavy Cannabis Use, Whereas Reactivity in the Dorsal Striatum Mediates Dependent Use. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 4 (8), 751-762.

- Orr et al, 2019. Grey Matter Volume Differences Associated With Extremely Low Levels of Cannabis Use in Adolescence. J Neurosci. 39 (10), 1817-1827. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3375-17.2018

- Gorey et al, 2019. Age-related differences in the impact of cannabis use on the brain and cognition: a systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019; 269(1): 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-00981-7

Last Updated: Apr 30, 2020