A new study from the researchers at the University of California, Berkeley has shown that progressively declining quality of sleep among those in their 50s and 60s could be indicative of protein tangles within their brains that could lead to later development of Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers point out that healthy sleep could be a key to long term brain health.

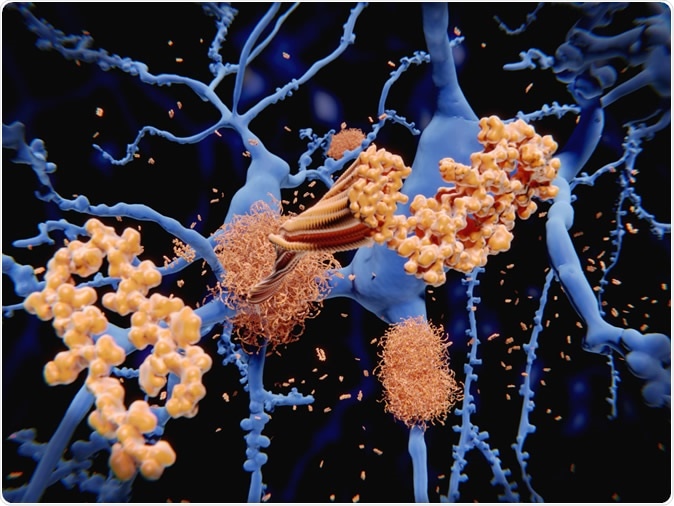

Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid-beta peptide accumulates to amyloid fibrils that build up dense amyloid plaques. 3d rendering - Image credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock

Study lead author Matthew Walker is a sleep researcher and professor of psychology. He explained the importance of sound sleep in a statement saying, “Insufficient sleep across the lifespan is significantly predictive of your development of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the brain. Unfortunately, there is no decade of life that we were able to measure during which you can get away with less sleep. There is no Goldilocks decade during which you can say, ‘This is when I get my chance to short sleep.’”

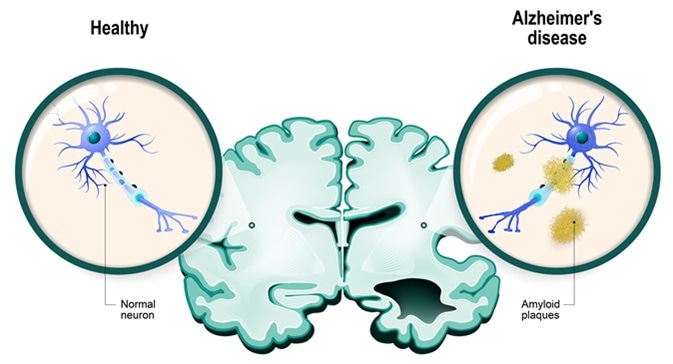

First author of the study was graduate student Joseph Winer who noted that adults with reduced quality and quantity of sleep per night showed brain changes. The team found that these adults tended to have more beta-amyloid protein in their brains as they grew older. These tangles of beta amyloid protein are hallmarks of dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease and can be detected using a positron emission tomography, or PET scan. Among adults with decreasing sleep in their 50s and 60s there was a rise in amount of tau protein tangles in the brain. Both beta amyloid and tau protein clusters are related to a higher risk of developing dementia.

Human brain, in two halves: healthy and Alzheimer's disease. Healthy neuron and neuron with amyloid plaques. Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

The team suggests that all older patients on their visits to the GPs or doctors need to be asked about their sleep quality, patterns and any changes in sleep quality or quantity. Improving sleep in older adults could help delay the onset of dementias in them, write the authors. They add that common sleep problems among middle aged and older adults include sleep apnea and insomnia. The authors of the study suggest treatment for apnea that can lead to snoring and disruption of sleep. They suggest cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and incorporation of healthy sleep hygiene habits by counselling to improve sleep among older adults.

Winer said, “The idea that there are distinct sleep windows across the lifespan is really exciting. It means that there might be high-opportunity periods when we could intervene with a treatment to improve people’s sleep, such as using a cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia.” He added, “Beyond the scientific advance, our hope is that this study draws attention to the importance of getting more sleep and points us to the decades in life when intervention might be most effective.”

For their study called the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study (BACS), the team included 95 healthy older adults. The maximum age of the participants was 100 years, the researchers wrote. These participants next had their brains scanned using PET scans. The scans revealed the beta amyloid and tau tangles in the brains of some of the individuals. The participants’ brain waves were recorded over a single eight hour sleep at the UC Berkeley sleep lab when they had to wear a cap with 19 electrodes that recorded a continual electroencephalogram (EEG).

They found that participants who had more amounts of tau proteins in their brains also more likely to have the synchronized waves in their brains that are seen when people get a good night’s sleep. They explained that when the brain sleeps, there are synchronization of slow brain waves throughout the cortex. These come with bursts of fast brain waves called sleep spindles during the deep or non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, the researchers explain. The synchronization reduced among adults who had more tau protein in their brains. They called this an impaired sleep signature and found it to be associated with the abnormal tau protein clusters in the brain. Walker explained, “There is something special about that synchrony. We believe that the synchronization of these NREM brain waves provides a file-transfer mechanism that shifts memories from a short-term vulnerable reservoir to a more permanent long-term storage site within the brain, protecting those memories and making them safe. But when you lose that synchrony, that file-transfer mechanism becomes corrupt. Those memory packets don’t get transferred, as well, so you wake up the next morning with forgetting rather than remembering.”

Walker said that their team has been working on this for some time now and they have shown earlier the importance of the synchronization of the brain waves and memory functions. He added, “It is increasingly clear that sleep disruption is an underappreciated factor contributing to Alzheimer’s disease risk and the decline in memory associated with Alzheimer’s. Certainly, there are other contributing factors: genetics, inflammation, blood pressure. All of these appear to increase your risk for Alzheimer’s disease. But we are now starting to see a new player in this space, and that new player is called insufficient sleep.”

Winer added, “The leading hypothesis, the amyloid cascade hypothesis, is that amyloid is what happens first on the path to Alzheimer’s disease. Then, in the presence of amyloid, tau begins to spread throughout the cortex, and if you have too much of that spread of tau, that can lead to impairment and dementia.” Walker explained, “A lack of sleep across the lifespan may be one of the first fingers that flicks the domino cascade and contributes to the acceleration of amyloid and tau protein in the brain.” He urged people to visit their doctors if they are having difficulty sleeping. “The goal here is to decrease your chances of Alzheimer’s disease,” he said as he signed off.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Source:

Journal reference:

Sleep as a potential biomarker of tau and β-amyloid burden in the human brain, Joseph R. Winer, Bryce A. Mander, Randolph F. Helfrich, Anne Maass, Theresa M. Harrison, Suzanne L. Baker, Robert T. Knight, William J. Jagust and Matthew P. Walker, Journal of Neuroscience 17 June 2019, 0503-19; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0503-19.2019