Researchers have found that editing of the genes of the bacteria present in the guts of mice could help reduce the inflammation and associated risk of colorectal cancers. The research from the UT Southwestern scientists has been published this week in the latest issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine. The study is titled, “Editing of the gut microbiota reduces carcinogenesis in mouse models of colitis-associated colorectal cancer.”

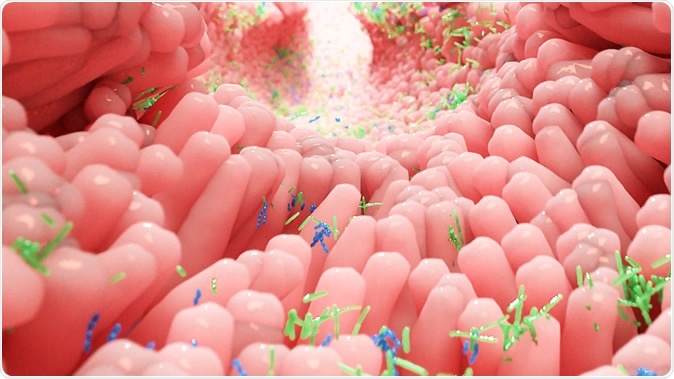

Human microbiota in the intestine. Illustration Credit: Alpha Tauri 3D Graphics / Shutterstock

According to researchers this study could be the beginning of novel approaches to cancer prevention among individuals who are at risk of chronic intestinal inflammation. They explain that over 1.6 million Americans suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with half suffering from ulcerative colitis and the other half suffering from Crohn’s disease. Dr. Ezra Burstein, Professor of Internal Medicine and Molecular Biology and Chief of UT Southwestern’s Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, lead author of the study, explained that persons with IBD have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancers. Colorectal cancers have been listed as the third most common cancers and the second largest cause of cancer-related deaths around the globe says the World Health Organization. Further the risk of colorectal cancers rises by three to seven times in persons who suffer from IBD. Dr. Burstein said, because of this persons suffering from IBD are screened regularly for colorectal cancers. They get three to ten times more number of colonoscopies compared to normal individuals, he said. Co-author Dr. Sebastian Winter, Assistant Professor of Microbiology and Immunology and a W.W. Caruth, Jr. Scholar in Biomedical Research explained that those suffering from IBD have a clear imbalance and alteration of their microbiome or gut bacteria. Their bacterial colonization in the gut is significantly different from those who have normal intestines.

Burstein explained that this study showed that the risk of colon cancers could be reduced if the gut microbiome could be altered in the mice. He said in a statement, “The most significant finding in this study is that manipulating the intestinal microbiome is sufficient to affect the development of tumors. One could envision a time in which medications that change the behavior and composition of the bacteria that live in the gut will be part of the treatment for IBD.” Dr. Winter said, “Our intestinal tract is teeming with microbes, many of which are beneficial and contribute to our overall health. Yet, under certain conditions, the normal function of these microbial communities can be disturbed. An overabundance of certain microbes is associated with increased risk for the development of diseases, including certain cancers.”

These researchers last year had published a study in the journal Nature that outlined the fact that during inflammation certain metabolic pathways are activated within some of the gut bacteria. If those pathways are targeted, the numbers of these bacteria could be reduced, they had noted. As they reduced the number of these bacteria, the inflammation could also be reduced. The effect of such intervention was not seen in persons with a healthy gut microbiome. Among mice with inflammatory reactions, this approach reduced the risk of gut inflammation or colitis, wrote the researchers.

“For example, most E. coli (Escherichia coli) bacteria are harmless and protect the human gut from other intestinal pathogens such as Salmonella, a common cause of food poisoning. However, a subset of E. coli bacteria produces a toxin that induces DNA damage and can cause colon cancer in research animals. We developed a simple approach – giving a water-soluble tungsten salt to mice genetically predisposed to develop inflammation – to change the way potentially harmful E. coli bacteria generate energy for growth. Restricting the growth of these bacteria decreased intestinal inflammation and reduced the incidence of tumors in two models of colorectal cancer,” Dr. Winter said. They used tungsten to reduce the genotoxins. The team wrote, “Oral administration of sodium tungstate inhibited E. coli molybdoenzymes and selectively decreased gut colonization with genotoxin-producing E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae.”

This study’s first author was Dr. Wenhan Zhu, a postdoctoral researcher in the Winter laboratory. This approach of precision editing of the genetic codes of the bacteria is a shift from the usual approach wrote the researchers. This would help reduce inflammation in the patients during flare ups of the IBD said the researchers. “Here, we present evidence that targeting the gut microbiota can be sufficient to affect tumor formation in a significant and meaningful way,” Dr. Winter said. “As with our 2018 paper, this is a proof-of-concept study that will guide us in developing future drugs with similar activity and less toxicity,” he added.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Welch Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Cancer Society, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

Source:

Journal reference:

Editing of the gut microbiota reduces carcinogenesis in mouse models of colitis-associated colorectal cancer, Wenhan Zhu, Naoteru Miyata, Maria G. Winter, Alexandre Arenales, Elizabeth R. Hughes, Luisella Spiga, Jiwoong Kim, Luis Sifuentes-Dominguez, Petro Starokadomskyy, Purva Gopal, Mariana X. Byndloss, Renato L. Santos, Ezra Burstein, Sebastian E. Winter

Journal of Experimental Medicine Jul 2019, jem.20181939; DOI: 10.1084/jem.20181939, http://jem.rupress.org/content/early/2019/07/26/jem.20181939#ref-list-1