Lead author Fatma Deniz says, “At a time when more people are absorbing information via audiobooks, podcasts and even audio texts, our study shows that, whether they’re listening to or reading the same materials, they are processing semantic information similarly.”

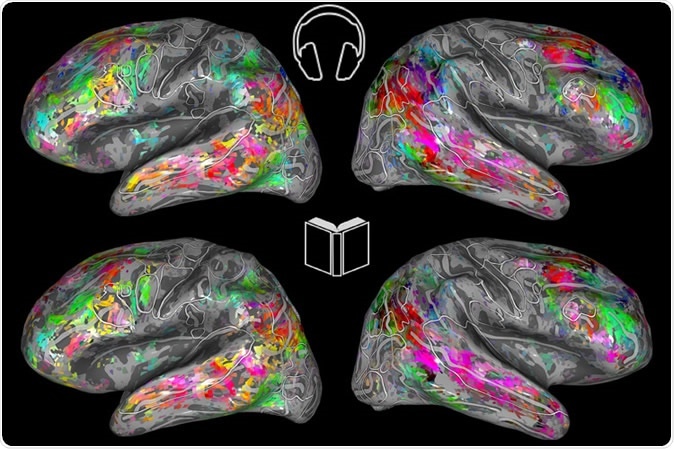

Color-coded maps of the brain show the semantic similarities during listening (top) and reading (bottom). (Image by Fatma Deniz)

The current team of neuroscientists at the University of California, Berkeley, has already generated a set of maps of the brain which allows them to tell which part will be stimulated by different kinds of words. The finding that words that mean the same or belong to the same category activate the same areas in the brains of different people has to do with the significance of language. Human languages depend intensively on the ability of the other person to understand the meaning of the word, spoken or written. Earlier studies showed that spoken words activated multiple cortical regions in the human brain according to their meaning (semantics), but broader meanings are represented over larger areas of the brain.

The study was focused on finding out at what level meanings were linked to specific brain areas in different people. To do this, they used an imaging procedure called functional MRI (fMRI) that can show brain activity in terms of differential blood flow. The participants in the study first listened to several stories from a podcast called “The Moth Radio Hour”, and then read them, over several hours.

During these two segments of time, their brains were scanned to detect areas of increased blood flow at each moment. Finally, they compared the areas of the brain that were activated by reading or listening, comparing them to the time-coded transcripts of the stories. This helped them find out which bit (voxel) was activated by which word.

The researchers also classified thousands of words by their relation to one another, such as mental, social, emotional, numeric, tactile (to do with touch), animals, and so on. This helped them find the semantic associations with different brain areas in each context and in each individual. A single word may activate many different areas of the brain because of the many different shades of meaning it may possess.

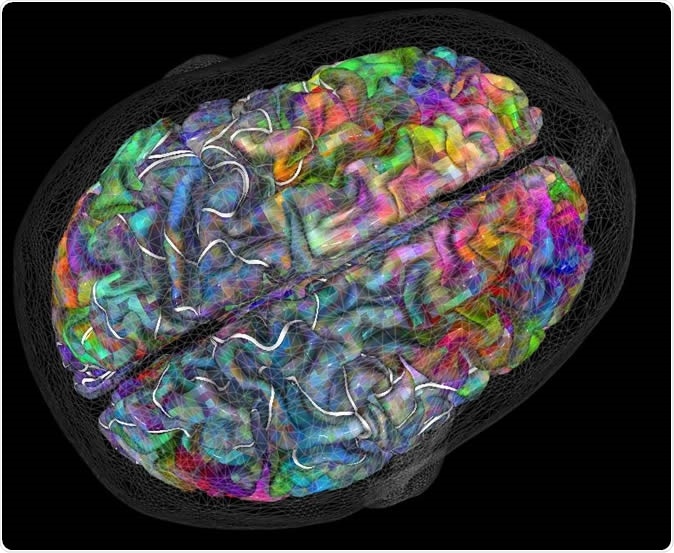

Next, they created brain models to describe the meaning-related selection of brain areas. In the beautiful 3-D map, which covers one-third of the brain cortex, if not more, words look like color-coded butterflies, and are placed on flattened representations of the cortex. The brain cortex is the outermost layer of the brain or gray matter, which contains the neurons dealing with sensory and motor information. It helps researchers to accurately predict the area of the brain that will be activated in response to each word. This interactive brain map is available online here.

The brain dictionary

The researchers found that both listening and reading produce the same type of response related to the word meaning in the same areas of the brain concerned with giving meaning to words. One form of learning was the same as another, and either could be used to predict the responses obtained using the other. The conclusion may be that no matter how you receive the information, the meaning is processed by the same brain areas.

Deniz says, “We knew that a few brain regions were activated similarly when you hear a word and read the same word, but I was not expecting such strong similarities in the meaning representation across a large network of brain regions in both these sensory modalities.”

This could help understand how stroke-affected people, for instance, suffer with language due to damage to brain areas that process the meaning of words, by comparing the brain activation in such groups with that occurring in healthy people. The same could be done for people with epilepsy, other forms of brain injury, and in other language-processing disorders.

These maps could also help modify the way dyslexia is treated. Dyslexia is a disturbance of brain development that affects the way children deal with language, and seriously impacts their ability to read. The researchers hope to find out which modality of language these children respond to best, so that it can be made a part of classroom teaching.

Researcher Fatma Deniz also says, “It would be very helpful to be able to compare the listening and reading semantic maps for people with auditory processing disorder.” In such conditions, people are not able to make out the differences between the different sounds that comprise a word. This could be better understood using this brain map.

Researchers plan to continue mapping the activity of the brain in relation to the meanings of different words in other languages, and in people who are known to have learning difficulties due to impaired language processing.

The study was published in the Journal of Neuroscience on 19 August 2019.

Source:

Journal reference:

The representation of semantic information across human cerebral cortex during listening versus reading is invariant to stimulus modality. Fatma Deniz, Anwar O. Nunez-Elizalde, Alexander G. Huth and Jack L. Gallant. Journal of Neuroscience 19 August 2019, 0675-19; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0675-19.2019. https://www.jneurosci.org/content/early/2019/08/16/JNEUROSCI.0675-19.2019