Cancer immunotherapy is a form of treatment in which the body’s own immune cells are recruited to overcome the tumor. However, it is only useful in a few tumors, because of tumor immunity where tumor-associated immune cells work to protect the tumor against attack.

Now, researchers have come up with a new way to outsmart tumor immunity, selectively removing one type of tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) which supports tumor growth. This activates other immune cells to wipe out the tumor.

Working in tandem with other scientists in France, the UK and the USA, a brilliant team at Aarhus University, Denmark, has shown that malignant melanoma, a deadly form of skin cancer, can be successfully treated using this method.

The immune system is unique in its ability to fight foreign intruders. It is marvelously precise in targeting the cancer cell alone, dynamic in its adaptation to changing tumor antigens, and capable of storing long-term memories of the tumor antigens to prevent future recurrences of the cancer. However, it suffers from a crucial disadvantage: the tumor’s ability to mask its true face, deceiving the body into putting up with it or even helping it grow instead of fighting it. To do this, the tumor creates its own microenvironment, within the broader environment of the whole body. This contains tumor-associated immune cells, some of which shield the tumor and promote its growth, while others suppress it.

Conventional immunotherapy seeks to activate cell-killing T lymphocytes, one type of immune cell, to recognize, bind to and kill the tumor cells. Another arm of this treatment seeks to enhance the killing power of immune cells to make them more effective. A third aspect is recruiting additional immune components to mount a stronger immune response.

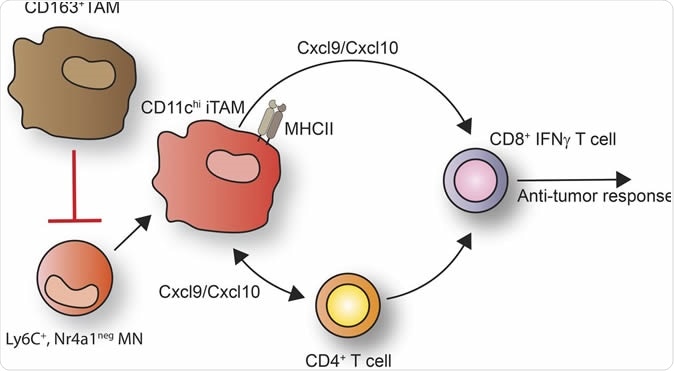

Specific targeting of CD163+ TAMs mobilizes inflammatory monocytes and promotes T cell–mediated tumor regression. Credit: JEM by Rockefeller University Press

The study

In this new study, the researchers focused on removing one specific subtype of tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) which has a protein called CD163 on the cell surface. They selected this cell type because it suppresses immune responses against the tumor. These macrophages treat the cancer cell as a normal part of the body, and actively help it to grow back if it is cut away, like any other tissue injury. Previous research has shown that tumors with an increased number of CD163 TAMs have a worse prognosis.

Describing the CD163 TAMs as “a kind of ‘peacekeeping’ force”, researcher Anders Etzerodt said the current work was focused on removing these forces so that the body’s own immune attack cells could be mobilized. These are mostly in the form of other macrophage subtypes. The effect of their mobilization is, in Etzerodt’s words, “The T cells and a number of other macrophages collaborate to attack the tumor. What's interesting is that the whole thing happens by itself as soon as we remove a tenth of the macrophages that express CD163.”

In other words, the CD163 macrophage subtype appears to act as gatekeepers, deciding which immune cells can be in the tumor’s microenvironment, or allowed to infiltrate the tumor itself. This finding was an important result of the current study.

The result

Selective removal of a tenth of the CD163 TAM activated another subtype of bone marrow-derived immune cell called monocytes which were Ly6C positive. These recruited another TAM subtype which has the CD11Chi antigen as well as a class of molecules called MHC II on its surface. These cells then released powerful chemical signals that attracted the subset of T cells that are positive for the CD8 antigen and produce the cytokine interferon-γ, a molecule which enhances the antitumor activity of these cells. The CD11Chi macrophages also attract another subset of T cells with CD4 antigens, which recognize the MHC II molecules. The two T cells types mount a massive attack on the tumor, which is seen as a large influx of activated T cells into the tumor and resulting tumor shrinkage.

Another conclusion was that it is possible to use chemotherapy with great precision to selectively take out only the macrophages that are associated with a poor patient survival outcome, leaving other helpful macrophages intact.

The study was carried out in mice with melanomas that resisted conventional immunotherapy. Its breakthroughs will now have to be replicated in mice with other types of cancer, and in humans with melanoma. It could take 10 years or more before the first ripples of this study actually reach clinical practice. This is due to the need to rule out undesirable acute and long-term effects from depleting CD163 macrophages, and to find funding partners and researchers for clinical trials.

The researchers are exploring the success of this technique with ovarian and pancreatic cancer. However, Etzerodt says, “I believe we are well-prepared with strong proof-of-concept data and patent applications.”

The study was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine on August 2, 2019.

Journal reference:

Specific targeting of CD163+ TAMs mobilizes inflammatory monocytes and promotes T cell–mediated tumor regression. Anders Etzerodt, Kyriaki Tsalkitzi, Maciej Maniecki, William Damsky, Marcello Delfini, Elodie Baudoin, Morgane Moulin, Marcus Bosenberg, Jonas Heilskov Graversen, Nathalie Auphan-Anezin, Søren Kragh Moestrup, Toby Lawrence. Journal of Experimental Medicine. Published August 2, 2019. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20182124. http://jem.rupress.org/content/early/2019/08/01/jem.20182124