The frightening outbreak of mysterious respiratory illness linked to the use of e-cigarettes, or vaping, have shaken the medical community.

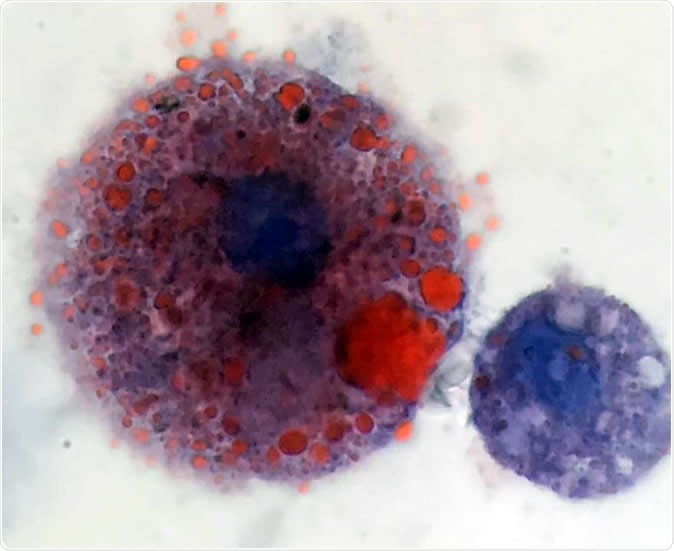

Lipid-laden macrophages found in patients with vaping-related respiratory illness. Oily lipids are stained red. Image Credit: Andrew Hansen, MD, Jordan Valley Medical Center

What are macrophages?

Macrophages are large immune cells that recognize and swallow foreign particles, and cell debris, processing them and eventually destroy them. They are formed as monocytes in the bone marrow and patrol the body in the bloodstream. Once they come across a site of infection or tissue injury of any kind, they respond by leaving the circulation and entering the injured place. As these encounter bacterial molecules or other cell signals, they are activated and transformed into macrophages. They become larger and more vacuolated. The many vacuoles or apparently empty spaces within the cytoplasm contain an assortment of deadly enzymes that help them to engulf dead and dying cells as well as bacteria, viruses and other harmful intruders. At the same time, they release enzymes to break down the particles within themselves, and also chemical signaling molecules (cytokines) to call in other immune cells to their aid. They exist in every tissue of the body, though they are known by different names, such as the brain microglia. They act as the first line of defense in protecting the body against infection.

They also help develop nonspecific or innate immunity, presenting the characteristic signature molecules of the bacteria they ingest on their surfaces. These can then be presented to other immune cells to let them know about the invasion, and thus this encourages the body to mount an effective immune response to wipe out the threat.

Digital medical illustration depicting a macrophage (white blood cell) attacking pathogens with its pseudopodia. 3D rendering - Illustration Credit: David Marchal / Shutterstock

What is vaping?

Vaping refers to the practice of inhaling smoke from electronic nicotine delivery systems, also called ENDS or e-cigarettes, which has recently caused hundreds of cases of lung injury. The mechanism causing such an injury is unknown, and hence the current report is of significance in possibly directing research into the immediate cause of lung damage. It is already known that ENDS smoke includes vapor from several flavorants, which may give rise to new and possibly harmful compounds on mixing and aerosol formation. The e-cigarettes are also being released in the form of cannabis-containing devices, where cannabis oil and cannabis concentrates are smoked.

Woman using electronic cigarette - Image Credit: Eldar Nurkovic / Shutterstock

What did the researchers find?

Vaping-related injury begins with symptoms like breathlessness, cough, nausea and abdominal pain, and vomiting, with signs of fluid clogging the lung. However, tests show no evidence of bacterial, fungal or viral lung infection, and the condition fails to respond to treatment for bacterial pneumonia. The fluid from the very smallest lung passages and the alveoli of the lung, that is, the minute air sacs where oxygenation of the blood happens, is obtained via a technique called bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). This refers to washing out the smallest airways of the lung and retrieving the washed-out solution. BAL fluid in vaping-related lung injury shows almost equal numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. These are immune cells, but in this condition the latter was remarkable for being loaded with fat visible by special staining with a dye called Oil Red O.

These cells contain fat that does not come from aspiration, for instance. Moreover, the CT scans show that the lung lesions seen on imaging do not resemble those that typically occur with aspiration pneumonia due to the inhalation of fatty material. However, a variety of imaging patterns have been seen in such patients, and this may indicate that multiple mechanisms are at work to produce this illness. In the present series of six cases, lipoid pneumonia seems to be the lung injury at work. This refers to an acute inflammatory response of lung tissue to the presence of fats in the alveolar compartment and is most commonly seen when oily substances are inhaled. Most case occurs in older patients. However, in the present series of patients following vaping, the CT scans do not show a finding that is typical of most cases of lipoid pneumonia, namely, fat attenuation.

Nonetheless, the presence of the fatty macrophages was intriguing. While these findings are not enough to suggest a diagnosis of vaping syndrome at present, they may serve as a useful marker of this condition once lung infection has been excluded. In many cases the vaping-related lung injury is severe enough to require acute ventilatory support and may take up to two weeks to resolve, though lasting damage is rare.

What do we learn?

Researcher Scott K. Aberegg says, “These cells are very distinctive, and we don't often see them. That made everybody start to think carefully about why they were there. We need to determine if these cells are specific for the illness or whether they are also seen in vaping patients who are not ill and don't have symptoms. If they are only seen in patients who get sick, we can begin to make some connections between what we're seeing in the lipid laden macrophages and whatever components of the vaping oils may be causing this syndrome.”

The finding was reported in the New England Journal of Medicine on September 6, 2019.

Journal reference:

Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. Sean D. Maddock, Meghan M. Cirulis, Sean J. Callahan, Lynn M. Keenan, Cheryl S. Pirozzi, Sanjeev M. Raman, & Scott K. Aberegg. New England Journal of Medicine. September 6, 2019 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1912038, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1805186?query=recirc_top_ribbon_article_1