Cancer of the pancreas

Pancreatic cancer begins in the pancreas, a fish-shaped organ located deep in the abdomen, behind the stomach, about 6 inches by 2 inches in size. The main part is just behind the junction of the stomach with the small intestine, while the body and tail continue to the left, behind the stomach to end near the spleen. This organ produces the greatest amount of strong digestive enzymes, as well as the key hormones insulin and glucagon, which regulate glucose metabolism. The enzymes are produced by exocrine cells, which are the typical site of origin of a pancreatic cancer. The enzymes make their way through small tubes or ducts which merge to form the pancreatic duct. This in turn joins the common bile duct, the tube which carries bile from the liver, to empty into the small intestine near its beginning.

At present, there are about 56,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer each year in the US, and it is not effectively treatable. The mortality rate is high, at over 90% within five years of diagnosis. It is difficult to diagnose since the symptoms are late to set in. They include abdominal pain, yellowing of the eyes, and weight loss, and are usually found only with advanced disease.

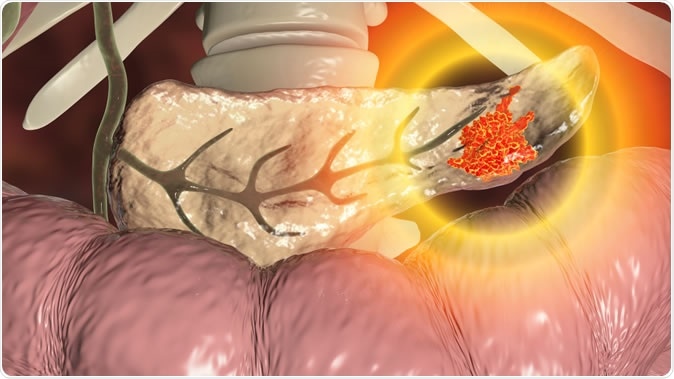

Pancreatic cancer, malignant tumor of pancreas, 3D illustration. Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Two-drug combination

The observed efficacy of this two-drug combo, using newer versions of approved drugs as an off-label use, begs for immediate verification of the results in humans. The scientists are planning the future clinical evaluation of these drugs in collaboration with oncologists at Oregon Health & Science University.

The drugs used are L-asparaginase and a MEK inhibitor. L-asparaginase is an enzyme that breaks down asparagine and glutamine to aspartic acid and glutamic acid, respectively. These are all important amino acids. Asparagine is a key nutrient that is essential for protein synthesis. The inability to use this amino acid therefore effectively prevents tumor growth.

L-asparaginase is used to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemias. While highly effective, L-asparaginase is also associated with multiple adverse effects on the brain, liver, and pancreas as well as allergic reactions and impaired coagulation parameters which can cause clot formation in the brain or abnormal bleeding tendencies.

To compensate, the tumor cells activated a stress response pathway that leads to the synthesis of asparagine within the tumor cells. The MEK enzymes (mitogen/extracellular signal regulated kinase) are an essential part of the T cell receptor signaling pathway. The second drug, the MEK inihibitor, blocks a key enzyme in this pathway, and prevents asparagine synthesis as well as asparagine-dependent protein synthesis in the tumor cells. The MEK inhibitor is approved for the treatment of melanomas and other skin cancers. It can cause gastrointestinal effects, retinal damage, and cardiac effects.

This type of mechanism is called synergism, whereby two different pathways are utilized to attack the tumor’s growth and proliferation.

The scientists took the patient data from previous studies and used them as the basis for a computational analysis, which showed that this combination was likely to be successful in shrinking a majority of pancreatic tumors.

Implications

Researcher Rosalie C. Sears says, “It's clear we're not going to find a single magic bullet that cures cancer but will instead need several drugs that target multiple vulnerabilities. The study identifies a promising dual treatment for pancreatic cancer – one of the deadliest cancers – and I look forward to seeing these drugs tested.”

The experiment showed shrinkage of both melanomas and pancreatic tumors, but the scientists decided to focus first on clinical trials on the latter due to the complete lack of successful therapies at present.

Journal reference:

Pathria, G., Lee, J.S., Hasnis, E. et al. Translational reprogramming marks adaptation to asparagine restriction in cancer. Nat Cell Biol (2019) doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0415-1, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41556-019-0415-1