The study which has been termed the most comprehensive ever to examine the long-term adverse impacts of high cholesterol levels recommends early checking and action to reduce cholesterol levels through appropriate modifications of the diet and lifestyle, and medication.

Cholesterol – the universal molecule

Cholesterol is a waxy fat, a molecule found in the blood and in every cell of the body. At the same time, too much of certain types of cholesterol can produce an increased risk of heart disease and stroke. With this in mind, researchers say the earlier excessively high cholesterol levels are detected and treated through appropriate lifestyle changes and medications, the better will be the outcome.

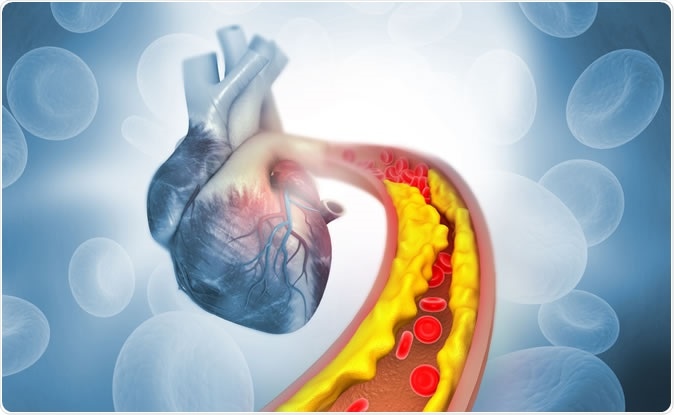

Cholesterol plaque in artery. 3d illustration Credit: Explode / Shutterstock

Cholesterol serves as an important component of the cell membranes, and also is the starting point for many hormones such as estrogen and testosterone, the sex hormones, as well as other steroid hormones like vitamin D, and other steroid compounds.

Two types of cholesterol are often quoted by medical professionals as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Good cholesterol is high-density lipoprotein (HDL) which trucks cholesterol from various peripheral sites of the body, such as fatty tissue, to the liver where it can be metabolized and stored properly. LDL, or low-density lipoprotein, is ‘bad’ cholesterol which consists of lighter, more foamy particles that carry cholesterol all through the body and can lead to arterial wall thickening by atherosclerotic plaque deposition. By subsequent narrowing of the arterial lumen, this process can cut off blood flow to the part supplied by the artery. Triglycerides are fat globules found in the blood after a fat-rich meal is absorbed.

Today, all blood cholesterol minus HDL levels is termed non-HDL cholesterol and this is said to be the most appropriate when used to determine the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

To reduce excessive levels of bad cholesterol in blood, statin drugs are often prescribed. Up to 8 million people in the UK alone are on these lipid-lowering medications. The estimated benefit is the prevention of a cardiovascular event (heart attack or stroke) in 1/50 people who stay on the drug for 5 years.

The study

The researchers retrieved data on cholesterol levels, gender, age, other risk factors for CVD like smoking, diabetes, height, weight, and blood pressure, on almost 300 000 people from 19 countries around the world, contained in the Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium dataset. They analyzed these variables and found that the levels of LDL were strongly associated with the risk of CVD over a period beginning in early adult life and stretching over the next 40-plus years. They also found a way to estimate long-term risk for CVD events with respect to non-HDL levels. Thirdly, they built a model to estimate how much benefit might accrue in case people without CVD at the time of intervention were treated with lipid-lowering drugs or other strategies.

This data enabled them to estimate the risk of a stroke or heart attack over the next 40 years in a person 35 years or more. This is a significant improvement over the currently used risk scores, whereby the doctor decides if the individual should be started on drugs that lower blood lipid levels. These scores can only predict the risk of CVD over the next ten years from the assessment date. When these are used for relatively young adults, the lifetime risk is likely to be much higher than is actually estimated. This may mean that intervention in this group is being unnecessarily delayed.

The findings

The CVD risk rose steadily with non-HDL levels, from 7·7% when it was <2·6 mmol/L to 33·7% at levels ≥5·7 mmol/L in women. For men, the risk at these non-HDL levels rose from 12·8% to 43·6%.

The group at highest lifetime risk for cardiovascular events was people below 45 years who had high LDL or triglyceride levels. By gender, they found that women below 45 years but with non-ideal HDL levels, and with two more risk factors for CVD, had a 16% risk of a CVD event (that did not result in death) by the age of 75 years. In older women with the same profile, the risk was 12%.

Men under 45 with non-HDL levels of 145-185 mg/dL had an almost doubled risk of a nonfatal cardiovascular event by the age of 75%, at about 30%, but the risk fell by 10% even with the same risk factors if the men were at least 60 years old.

In both these groups, the risk is increased in young adults. Researcher Barbara Thorand explains, “The increased risk in younger people could be due to the longer exposure to harmful lipids in the blood.” On the other hand, people who had reached the age of 60 without CVD were likely in better health overall, compared to those who had CVD by this time.

The effect of early intervention

Using theoretical calculations, the researchers found that the risk in men and women under 45 years could dip sharply to 6% and 4%, instead of the previous 30% and 16%, respectively, if the non-HDL cholesterol was reduced by half. This held true even if other risk factors like body weight were still present.

In other words, cutting high cholesterol levels at a younger age would result in still more striking risk reductions. Many cardiologists will rejoice at still further reason to prescribe statins to a still greater number of people.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean all young adults with high cholesterol levels should start taking statins. Researcher Stefan Blankenberg says, “I strongly recommend that young people know their cholesterol levels and make an informed decision about the result - and that could include taking a statin.”

Other cardiologists agree, saying that the study adds to the solid evidence that cholesterol in excessive amounts is a big risk factor for strokes and heart attacks. Sir Nilesh Samani of the British Heart Foundation says, “For some people, taking measures at a much earlier stage to lower cholesterol, for example by taking statins, may have a substantial benefit in reducing their lifelong risk from these diseases.” Preventive cardiologist Roger Blumenthal concurs, saying, “This article reinforces the idea that earlier intervention, to keep cholesterol levels in a desirable range, rather than delaying to much later in life, needs to be discussed clearly and early.”

On the other hand, statins are not a substitute for healthy and wise choices when it comes to eating good food or taking regular exercise or learning to cope with stress. Moreover, the researchers also pointed out that though serious adverse events are rare, the long-term adverse effects of taking statins for many decades have not yet been explored.

The American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines begin with weight reduction or at least maintenance, and a more active lifestyle that incorporates at least 30 minutes of exercise 5 days a week. They also advise a no-smoking, no junk food lifestyle, restricting calories to the required 1,600 to 2,400 calories per day and 2,000 to 3,000 calories per day for adult women and men, respectively. In the face of unchanged or inadequately controlled cholesterol levels, early statin therapy is considered ideal to reduce the risk of a cardiovascular event.

With heart disease claiming more lives than any other condition worldwide, cardiologist Nieca Goldberg says, “Diet and exercise is the mainstay, it remains the foundation of heart disease prevention that may be hard for some, but we can find ways for everyone to do it.”

Journal reference:

Application of non-HDL cholesterol for population-based cardiovascular risk stratification: results from the Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium Brunner, Fabian J Zeller, Tanja et al. The Lancet, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32519-X/fulltext