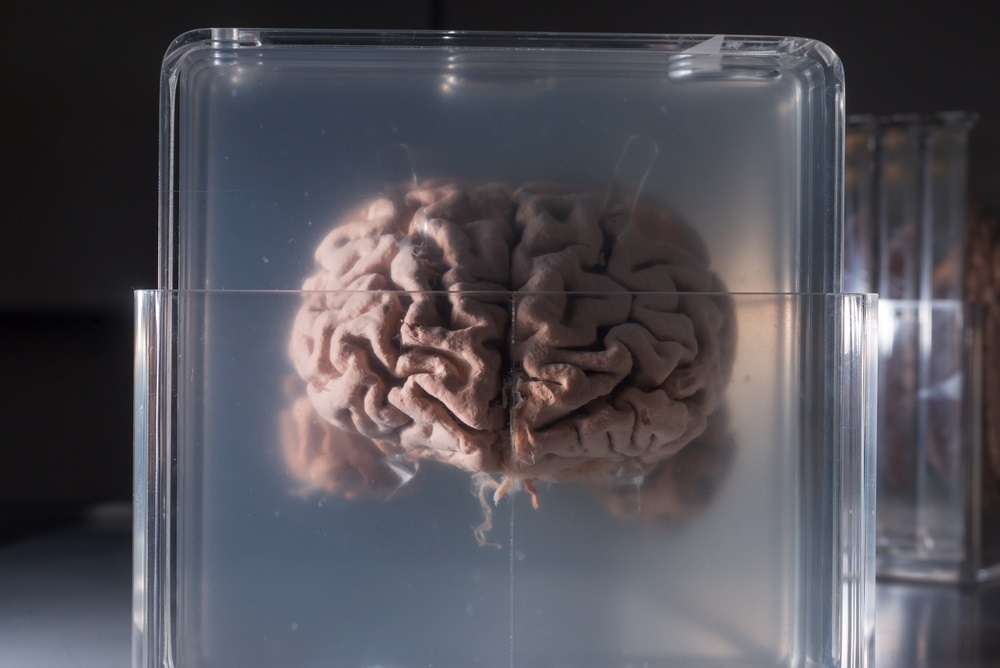

Scientists who investigated a 2,600 year-old brain preserved in an iron-age skull have found evidence to explain why it survived until modern times in a mud pit. The answers could shed light on the treatment of brain diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Image Credit: SubstanceTproductions / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: SubstanceTproductions / Shutterstock.com

A team of international researchers has found a clue to explain how the brain, which was from a man in Britain who died more than 2,000 years ago, survived all those years without decomposing. Published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, the study shows how the researchers studied the brain tissue for months, focusing on the proteins present in the tissue to help them better understand how the brain really works.

The brain, called the Heslington Brain, was first discovered inside a skull buried in a mud pit in Heslington, Yorkshire, England, in 2008. Many scientists claim that the brain is the oldest one ever found in Eurasia, being dubbed as the best-preserved brain worldwide. The brain dates to about 482 to 673 BC, which was the start of the Iron Age.

The analysis of the brain tissue showed that it was from a male who was likely decapitated. The brain tissue had withstood many factors but had managed to survive for thousands of years. Now, scientists have unlocked one of the mysteries surrounding the brain tissue.

Brain analysis

The researchers have carried out the first-ever detailed analysis of the brain tissue using powerful microscopes. The team scanned the brain with a focused beam of electrons. The brain was studied at a molecular level, focusing on the presence of proteins that are harder than any other material found in the brain.

They found more than 800 proteins in the tissue sample. Some were in good condition, and they were able to study and work up an immune response to them. Further, they found that the proteins had folded themselves into tight-packed stable aggregates that were more stable than those found in the normal and healthy brain today.

The formation of the aggregate explains how the brain was able to evade decomposition and got preserved for thousands of years. They also pinpointed that the environment where the skull was discovered had helped in the preservation. The fine-grain sediment was cold and wet, which may have warded off oxygen that the flesh-eating microorganism need to survive.

Implications for current practice

The study findings can help scientists today study brain diseases, such as dementia, that are related to protein folding and aggregate formation. Diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease involve the development of rogue proteins dubbed as amyloid and tau. These proteins work by killing brain cells when they clump together.

In the case of the preserved brain, it was the process of aggregate formation that allowed the brain to survive across more than 2,000 years. The discovery of the tight-packed aggregates provided new proof for the long-lasting stability of non-amyloid protein aggregates, which permit the preservation of brain proteins.

The brain tissue offers a unique chance to use molecular tools to examine how to preserve human brain proteins. Eventually, this could help scientists to find a way to battle dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

Dementia affects around 50 million people worldwide, with 10 million new cases each year. By 2030, the projected number of people with dementia is 82 million and 152 million by 2050.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that gradually damages memory and cognitive skills. In the long run, patients with the condition may have problems with simple tasks.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, and in the United States, it is the 6th leading cause of death.

Journal reference:

Pretzold, Axel, Lu, C.H, Groves, M., Gobom, J., Zetterberg, H., Shaw, G., and O’Connor, S. (2019). Protein aggregate formation permits millennium-old brain preservation. The Royal Society. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2019.0775