In an amusing but amazing turnaround, it seems the most foul-smelling compound on earth, called putrescine, could help relieve chronic inflammation, most importantly in the arterial thickening called atherosclerosis. This discovery is reported in the journal Cell Metabolism in January 2020.

Putrescine, spermine and spermidine are all organic compounds belonging to the polyamine class, and found widely within the human body, and in all animal meat, in fact. These seem to be vital ingredients for normal growth (“growth factors”) and are required for DNA regulation and protein synthesis. They also take up potentially damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS), and promote cell differentiation and proliferation, two processes vital in early embryonic life. Putrescine is also a by-product of bacterial breakdown of lysine and ornithine in the gut.

The chemical putrescine takes its name from its stench – the unmistakable odour of rotting or putrid flesh. The current study was focused on how the body normally removes dead cells, using macrophages. Macrophages are white cells, phagocytes that move around looking for things to ‘eat’ and thus rid the body of unwanted matter like bacteria, debris from normal cell activity, and inflammatory by-products.

The importance of efferocytosis

Study author Ira Tabas says, “It's estimated that a billion cells die in the body every day, and if you don't get rid of them, they can cause inflammation and tissue death. Removing these dead cells by a process called 'efferocytosis' (from the Latin 'to carry to the grave') is one of the body's most important functions.”

Apoptosis is the meticulously designed cell program in which the cell sets out to fade out of existence without causing harm to the rest of the body. The dead cell must be immediately removed by phagocytosis, or being engulfed by macrophages, to keep it from rotting and releasing cell debris which provoke inflammation. Autoantigens, or antigens belonging to the body’s own tissues but abnormally presented to the immune system as immune targets, perhaps because of their association with legitimate targets, could provoke autoimmune disease.

In normal circumstances, this process of removing dying or dead cells begins almost as soon as the cell dies. On the other hand, in people with atherosclerosis and other chronic inflammatory conditions, efferocytosis appears to lag. This may be the trigger for the formation of the characteristic atherosclerotic plaques that narrow, stiffen and may finally obstruct the vessels, leading to serious and even fatal limitation of blood supply to the vital organs of the body.

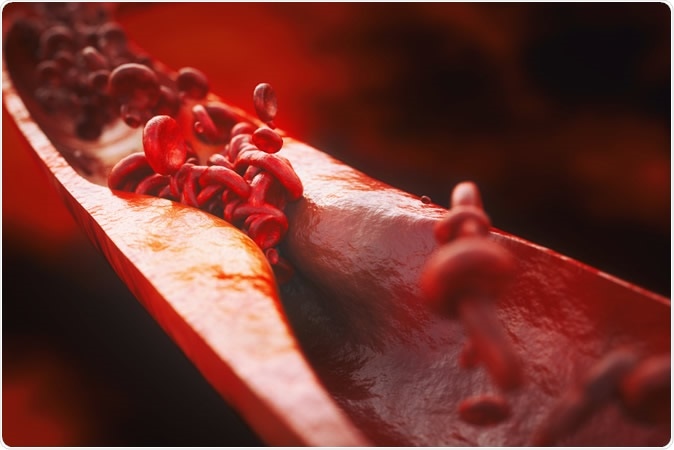

Closeup of a atherosclerosis- 3D rendering. Image Credit: Crevis / Shutterstock

The study and its findings

To analyze the process and its underlying triggers, the team of researcher devised a system of human macrophages and cells in the process of dying within a laboratory dish, to just see how things proceeded. At this point, they found how putrescine worked in inflammation.

The macrophages engulf dead cells but break down the cell matter into its constituent amino acids, including arginine. They then convert the nitrogen-containing arginine into putrescine via an enzymatic reaction. Putrescine is important because it activates the Rac1 protein, which is a green flag for the macrophages, stimulating them to go ahead and eat the rest of the dead cells.

If this was the case, it could mean that putrescine wasn’t working properly in people with atherosclerosis. To confirm or exclude this hypothesis, the researchers looked at mice with this condition.

The findings showed that lack of arginase 1, an enzyme which is essential to convert arginine to putrescine, was associated with intensifying atherosclerosis in mice. however, when the researchers mixed putrescine into their drinking water as a kind of supplement, they observed better and more efficient macrophage function and fewer or less obvious plaques.

The outcome is better and more prolonged efferocytosis, which promotes improved wound resolution.

Implications

If this finding is validated, it could mark the use of putrescine to treat atherosclerosis. And why stop there? It could be possible one day to treat Alzheimer’s disease and other chronic inflammatory disorders using putrescine.

Some purists still object to the use of this compound because of its dismaying smell. However, says Tabas, “When you dissolve putrescine into water, at least at the dosages needed to improve the plaques, it no longer gives off its odour. The mice drank it without any problem and show no signs of sickness.”

Tabas sums up: “Of course we do not yet know the feasibility and safety of using low-dose putrescine to ward off atherosclerotic heart disease and other diseases driven by defective efferocytosis. However, the study shows the potential of treating heart disease with compounds that help macrophages eat dead cells and that are currently in clinical trials for other indications.

Journal reference:

Arif Yurdagul, Manikandan Subramanian, Xiaobo Wang, Scott B. Crown, Olga R. Ilkayeva, Lancia Darville, Gopi K. Kolluru, Christina C. Rymond, Brennan D. Gerlach, Ze Zheng, George Kuriakose, Christopher G. Kevil, John M. Koomen, John L. Cleveland, Deborah M. Muoio, Ira Tabas, Macrophage Metabolism of Apoptotic Cell-Derived Arginine Promotes Continual Efferocytosis and Resolution of Injury, Cell Metabolism, ISSN 1550-4131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.01.001