The emergence of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology has spurred hope in both doctors and patients since it shows promise in treating a multitude of diseases, including cancer. For the first time in the United States, a team of scientists has shown that CRISPR-edited immune cells can be safely used to cancer patients.

CRISPR gene editing is a new technology that is powerful in editing genomes, allowing scientists to easily modify DNA sequences and gene function. The method has shown promise in many applications, including correcting genetic defects, improving crop yields, and preventing disease.

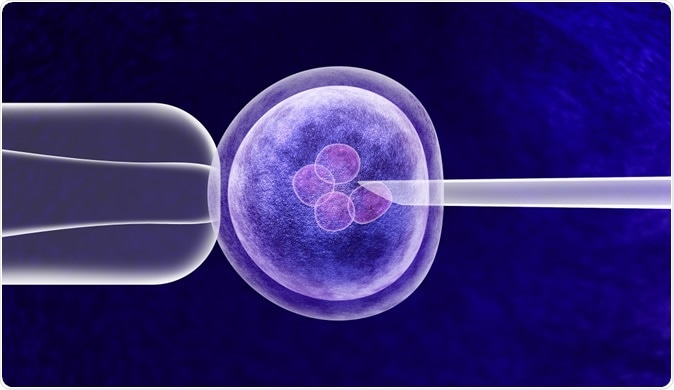

Image Credit: Lightspring / Shutterstock

CRISPR editing technique

The team injected CRISPR gene-edited immune cells into three people with advanced cancer without any serious side effects, which is dubbed as the first trial of its kind in the country. It’s also the first cancer trial of the technique to be published in the journal Science.

The newly published study follows the first report in 2019 showing that researchers used CRISPR technology to successfully edit three cancer patients’ immune cells.

The scientists believe that with the new trial, it may become a part of an innovative cancer treatment called immunotherapy. The focus of the treatment is to boost the body’s immune system to help it fight cancer. Though there are many ways to do this, one of the most popular involves reprogramming the immune system’s T cells, which fight off cancer cells, microbes, and other foreign invaders.

The team’s first human clinical trial shows the safety and feasibility of multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 editing to engineer T cells in three refractory cancer. The modified T cells that fight off cancer persisted for nine months on average, suggesting the treatment is effective and can be used with immunotherapy.

Immune cells are engineered to fight cancer

The body has a natural defense against a variety of foreign invaders, including cancer cells and pathogens. The immune cells fight off cancer, but in time, the aggressive tumor cells may overwhelm the immune system, building resistance to their powers.

The new study, injecting genetically edited immune cells, is closely related to CAR T cell therapy, wherein immune cells are engineered to help in battling cancer. However, they have differences. In the study, the team started collecting a patient’s T cells from the blood. Instead of providing the cells with a receptor against CD19, a type of protein biomarker for normal and neoplastic B cells, as well as follicular dendritic cells, the team utilized the CRISPR gene-editing tool to remove three genes.

The first edits removed the natural receptors of a T cell to help reprogram it to release or express a synthetic T cell receptor to allow the cells to look for and kill cancer cells. Further, the third edit removed PD-1, a protein found in T cells that aids in keeping the body’s immune responses in check and sometimes blocks T cells form performing their work.

"This new analysis of the three patients has confirmed that the manufactured cells contained all three edits, providing proof of concept for this approach. This is the first confirmation of the ability of CRISPR/Cas9 technology to target multiple genes at the same time in humans and illustrates the potential of this technology to treat many diseases that were previously not able to be treated or cured," June explained.

The three genes, including PD-1, were deleted using the technique and placed back in the body after six weeks. The patients survived for at least nine months.

The treatment may be promising but it doesn’t work for everyone. In some cases, the method works at first but then, they relapse later. The scientists hope to further study the technique and see if combining it with cancer treatments can make it more effective.

There are also safety concerns regarding technology. CRISPR may cause unintended changes to genomes that could trigger cancer development. Also, there is a risk that the edited genes can turn cancerous or attack healthy cells in the body. It is also possible that they go into self-destruction, triggered by a specific drug.

The scientists are still a long way and more research is still needed for the use of CRISPR gene-editing techniques in cancer treatment.

Journal reference:

Stadmauer, E., Fraietta, J., Davis, M., Cohen, A., Weber, K., and Lanca, E. et al. (2020). CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2020/02/05/science.aba7365