Soon, robots can take blood samples that can benefit both patients and healthcare workers, thanks to a new blood-sampling robot. A few years back, it was developed but was only tested on plastic arms. Now, the robot has been successfully trialed on live humans.

A team of scientists from Rutger’s University has created a robot that can take blood samples from patients. The robot can perform as well or even better than people in drawing blood. The new machine will help many people and save time in clinics and hospitals.

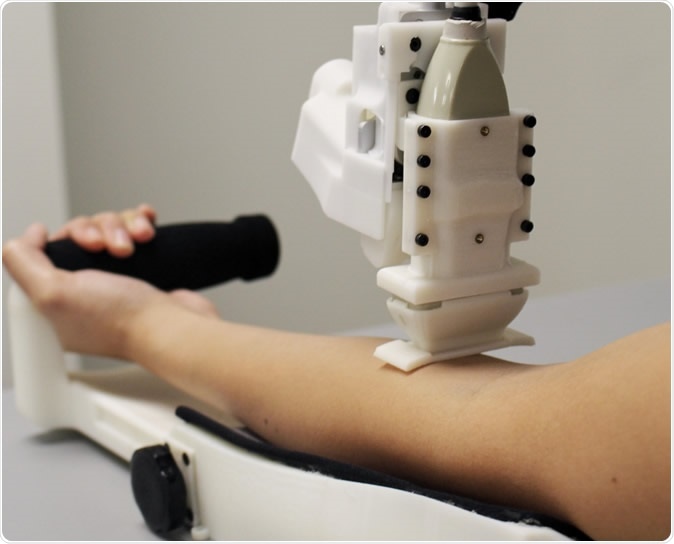

A prototype of an automated blood drawing and testing device. Credit: Unnati Chauhan

Venous extraction difficulties

Obtaining venous access for blood sampling or intravenous (IV) delivery is an important step inpatient care. From there, they can perform laboratory tests that can determine a diagnosis.

In some cases, depending on the healthcare professionals' experience and the patient’s physiology, blood sampling can be harder and may need additional shots before hitting the right vein. Difficulties in obtaining access to the veins may result in missed sticks and sometimes, injury to the patients. When vein access fails, it may require other personnel to try, or access another vein, hence, making the procedure time longer.

The blood-sampling robot

The device provides quick results, allowing healthcare professionals to spend more time treating patients in clinics and hospitals.

Now, the team has tested the machine in live humans and published their findings in the journal Technology. The results of the trial had a success rate of 87 percent for the 31 participants. For the 25 participants whose veins were easy to access, the device had a success rate of 97 percent.

The team designed the machine to combine ultrasound imaging and miniaturized robotics to determine the best vessels for access and robotically guide an attached needle toward the vein lumen center. This reduces the chance of going through the vein, making it rupture and requiring access to an alternative vein.

“In the future, this device can be extended to other areas of vascular access such as IV catheterization, central venous access, dialysis, and arterial line placement,” the researchers noted in their paper.

Study implications

Venipuncture involves inserting a needle into a vein to get a blood sample for testing and perform IV insertion and therapy. Across the globe, venipuncture is the most common clinical procedure, with 1.4 billion performed each day in the United States alone.

Healthcare professionals fail to hit the vein in 27 percent of patients whose vessels aren’t visible, 40 percent in patients whose veins aren’t palpable, and 60 percent of emaciated or abnormally thin or weak patients.

When there are repeated failures to get venous access or start an IV line, it increases the chances of phlebitis, infections, and thrombosis. These conditions require treatments and the need to target larger veins or arteries, needing greater costs and risks.

The new device saves time and money, giving doctors and nurses more time to spend on treating the patients. Further, the longer it takes to hit a vein, the greater the costs for the patient.

"A device like ours could help clinicians get blood samples quickly, safely and reliably, preventing unnecessary complications and pain in patients from multiple needle insertion attempts,” Josh Leipheimer, a biomedical engineering doctoral student in the Yarmush lab in the biomedical engineering department in the School of Engineering at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, said in a statement.

Soon, the device can be used in various procedures that require obtaining venous access, including dialysis, central venous access, catheterization, and putting arterial lines. The team says further polishing is needed to improve success rates.

Journal reference:

First-in-human evaluation of a hand-held automated venipuncture device for rapid venous blood draws Josh M. Leipheimer (1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA), Max L. Balter (1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA), Alvin I. Chen (1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA), Enrique J. Pantin (2Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, 1 Robert Wood Johnson Place, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA), Alexander E. Davidovich (3Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, 1 Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029-5674, USA), Kristen S. Labazzo (1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA), and Martin L. Yarmush (1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA) TECHNOLOGY 0 0:0, 1-10, https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S2339547819500067