The researchers from NYU Grossman School of Medicine and other institutions measure key proteins, which are workhorses that build molecular structures and signaling networks. They found that already-approved drugs that target proteins known as CDK12, PML, and SMARCA4 in other types of cancer may help in the treatment of endometrial cancer.

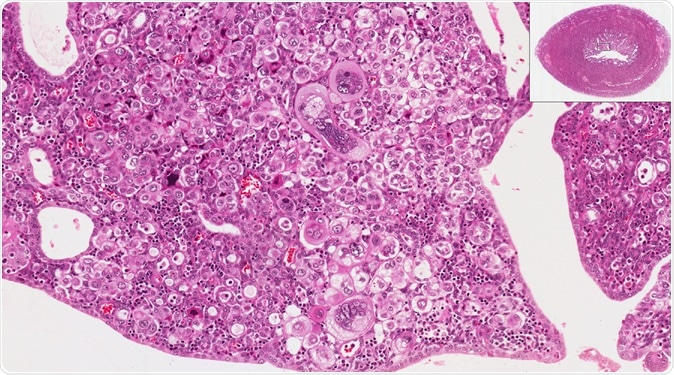

The new study from NYU Langone researchers provides an in-depth survey of the molecular players in endometrial cancer and suggests new treatment approaches. High and low power microscopic view of endometrium (uterus) to show endometrial cancer. Image Credit: vetpathologist / Shutterstock

More than genes

The new study built its work in The Cancer Gene Atlas (TCGA), which identified some of the genetic underpinnings of the disease in 2013. The scientists suggest that there is more to cancer than just genes.

To land to their findings, they analyzed 95 uterine tumors and 49 normal uterine tissue samples. With these, they measured the levels and modifications of molecular players, such as genes, microRNAs, circular RNAs, messenger RNAs, and proteins.

The team also studied the chemical changes to proteins, known as post-translational modifications, which is essential to determine when and where proteins are inactive or active. In a nutshell, the team collected 12 million measurements of differences between healthy cells and cancerous cells.

With the millions of measurements, the researchers developed a new method to determine tumors that are not aggressive now but will turn out to be as invasive as serous tumors, which are very potent and can kill patients.

At present, to determine how aggressive endometrial cancer is, doctors rely on biopsy or viewing the cells under a microscope. However, in the study, the team suggests that activity levels of some proteins can differentiate tumors that are more aggressive from less aggressive tumors.

Interestingly, the scientists also found that one process, which involved packing and unpacking genes, occurs more often than expected in cancer cells. Further, they found that a process called histone acetylation, which is a crucial part of the process, exists in endometrial cancer.

A promising avenue for treatment

The findings of the study allowed the researchers to devise a new way to determine which patients are most likely to benefit from a treatment called immune checkpoint therapy.

In the therapy, doctors use drugs like nivolumab and pembrolizumab to remove the barriers that most tumor cells use to escape the immune system. These immune checkpoint inhibitors fight cancer by blocking checkpoint proteins from binding with their partner proteins, preventing the turn off signal from being sent. Hence, the drugs allow the T cells of the immune system to kill cancer cells. It’s like boosting the power of the body’s immune system to fight cancer itself.

The new study now shows promise in treating patients who may need more aggressive treatment, reducing the risk of the tumor cells become invasive. Determining which patients would benefit from the drugs would help spare patients severe and unneeded side effects.

“For many years, scientists have been using genomics, the study of the genetic code, which is a very effective way but a relatively basic way to look at cancer. But if we add on all these extra levels--proteins, RNA, and the ways proteins talk to each other--then we can learn even more about how cancer is actually working,” Emily Kawaler, a student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and study co-author, said.

Journal reference:

Proteogenomic Characterization of Endometrial Carcinoma Dou, YongchaoAgarwal, Anupriya et al. Cell, https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(20)30107-0?