Until now, most studies have focused on the list prices of drugs, which means the wholesale prices. These, however, do not reflect the manufacturer's discounts, which typically reduce the final price by about a third. The researchers say, "pharmaceutical manufacturers have recently argued that, after accounting for rebates, net prices have increased at the rate of inflation."

The new study aims at providing a more accurate picture, according to researcher Inmanculada Hernandez, who says, "Previously, we were limited to studying list prices, which do not account for manufacturer discounts. List prices are very important, but they are not the full story. This is the first time we've been able to account for discounts and report trends in net prices for most brand name drugs in the U.S."

Earlier research by the same investigator concluded that there had been a steady increase in the list prices of prescription drugs over the last ten years.

To what extent have manufacturer discounts offset increases in list prices of branded pharmaceutical products in the US? Image credit: Shutterstock

The study

The researchers retrieved data on the money earned and the usage of over 600 brand name drugs, to trace the path of the list and net prices over the period 2007 to 2018. The net prices were estimated using the reported sales for each company product and the number of units sold in the U.S.

The findings

The scientists found that list prices went up by 159%, or just over 9% a year, even accounting for inflation. Net prices, which were the prices actually paid for the drug after the manufacturer discounts, 340B Drug Pricing Program, and other discounts, were still found to rise by 60%, or 4.5% a year. During this period, the rise in drug prices was a full three-and-a-half times higher than the inflation rate.

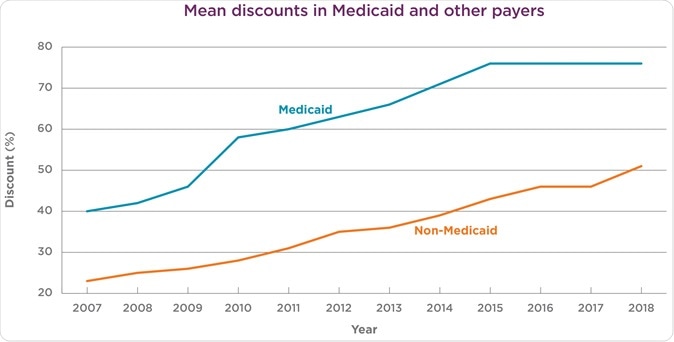

Medicaid discounts remain higher than for all other insurance types from 2007 to 2018. Image Credit: UPMC

The discounts to Medicaid went from 40% to 76%, and for other payers from 23% to 51%, knocking off about 62% of the increase in list price.

It was not until 2015 that net prices began to remain stable rather than to rise. However, the authors say that it doesn't mean patients will pay less. According to researcher Walid Gellad, "Net prices are not necessarily what patients pay. A lot of the discount is not going to the patient." Instead, most of the discount is intended for the insurers, both private and public. And in the case of copayments or coinsurance, the prices the patients pay are independent of such rebates, being fixed on the basis of the list price rather than the net price.

The prices for prescription drugs vary widely across different drug classes. The list and net prices are drifting apart more and more in the case of the insulins (260% and 50% respectively) or TNF inhibitors (166% and 73% increase, respectively). Statins and other drugs used to control blood cholesterol showed increases in list prices by 280% and net prices by 95% approximately.

With cancer drugs, both seem to move in a more synchronized manner, with a 60% list price increase and a 35% increase in net prices. For non-insulin diabetes drugs, the list prices went up by 165%, but the net prices went down by 1%, respectively, because of substantial discounts.

However, the most significant increase was with the drugs used to treat multiple sclerosis, the net prices went up to more than double over a decade, after adjusting for inflation. The list price went up by 440% and the net price by approximately 160% over this period.

Discounts

Medicaid rebates went up by 40% for all the above therapeutic classes except the cancer drugs, and were highest for the lipid-lowering drugs at the end of the study period, at 94%. Followed closely by discounts for insulins and TNF inhibitors, the discounts were lowest for multiple sclerosis and cancer drugs at around 50% to 55%.

Discounts to other payers increased the most, by 57%, for insulin, but also went up by over 40% for lipid-lowering drugs and the non-insulin diabetes agents. Both increases and final discounts were highest in these three drug classes in 2018. Except for cancer drugs, discounts for other drug categories went up by about 25% to 30%.

Discounts for Medicaid far outweigh those for other payers, probably because of regulatory rebates such as the mandatory discount for prices that have increased beyond the rate of inflation. With other insurers, the discounts must be negotiated. For this reason, the Senate Finance Committee is examining a proposal to automatically add in rebates based on inflation to Medicare, like the Medicaid discount.

Gellad sums up: "Net prices have stabilized over the last few years. But the stabilization of net price comes on top of large increases over the last decade, many times faster than inflation, for products that have not changed over this time period. In addition, this net price is an average, with substantial variability across payers and drugs."

Implications

The difference in the list price of drugs from a single manufacturer compared to that available from multiple sources is not reflected in net pricing, because of the heavy discounting required for competitive placement of branded drugs on pharmacy shelves.

Secondly, discounting can compensate for much of the list price increase, but leaves uninsured patients or those who have to pay part of the price exposed to such increases, because such rebates are not applicable to the final consumer. This can leave such patients unprotected against such steep hikes in net prices. Furthermore, finally, by making it more challenging to trace pricing trajectories, such discounting may encourage the use of drugs that have more significant discounts irrespective of the actual value of the drug to the patient.

Despite several limitations such as the comparison of only branded products and the difficulty of estimating rebates to all payers equally, the study concludes, "Mean increases in list and net prices were substantial, although discounts offset an estimated 62% of list price increases with wide variability across classes."

Journal reference:

Hernandez I, San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Gellad WF. Changes in List Prices, Net Prices, and Discounts for Branded Drugs in the US, 2007-2018. JAMA. 2020;323(9):854–862. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1012