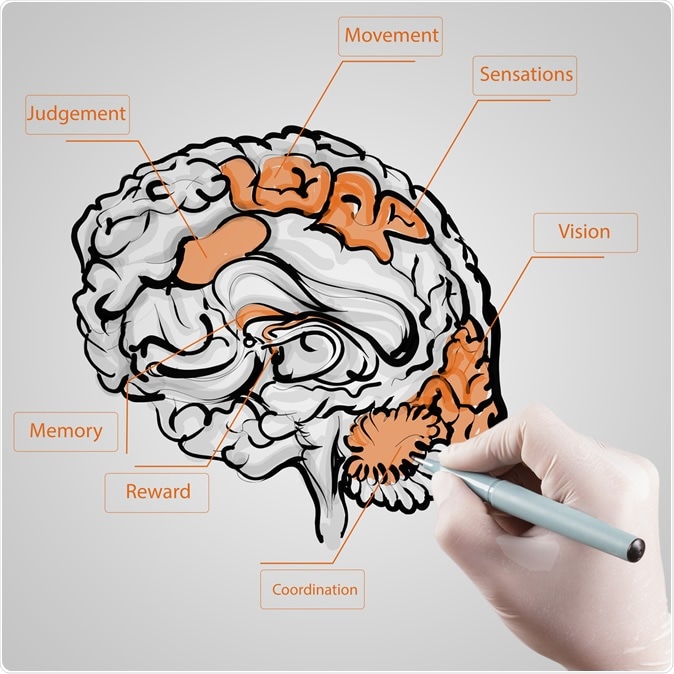

Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work. Image Credit: everything possible / Shutterstock

While it is true that these drugs improve focus, the mechanism was mostly unknown. Also popular as study aids, these drugs actually don't help the brain focus on the task itself. Instead, say the researchers, they turn the attention on to the rewards offered by the work and away from the costs, when it comes to completing a hard job. Thus, the rewards are emphasized rather than the costs, but there is no actual change in the individual's ability to do it.

Stimulant drugs like Ritalin are known to promote dopamine release from the striatum, which is a brain area that is important for motivating action, actually doing it, and the cognitive processes underlying it. It is established that dopamine is the neurotransmitter carrying information between neurons. Dopamine secretion affects motivation in both rats and humans to complete difficult tasks.

The study

The study was planned to examine the effect of stimulants on cognitive function, whether due to increase ability or improved motivation. It was designed to validate a new set of mathematical models developed by the same researchers, in which dopamine is shown to change the perceived benefits but not the costs of doing specific physical and mental actions.

The study included 50 healthy women and men aged 18 to 43 years, whose striatal dopamine levels were first assessed by imaging. This was followed by a set of increasingly difficult cognitive tests, some harder than others, which can be exchanged for specified amounts of money. The more complicated the test, the more the money that it generates in return.

Each participant performed the test series three times. One time was after taking a placebo, one after taking the stimulant methylphenidate, and once after taking sulpiride. This antipsychotic drug is used at higher doses to treat schizophrenia or depression. The experiment was undertaken as a double-blind study.

The results

The researchers found that the findings from the three rounds of testing confirmed the computer model in that a lower dopamine level prophesied the subject would avoid the most demanding task. That is, they were focused on the costs of doing it. A higher dopamine level predicted that the subject would pay more attention to how much money was on offer by doing the harder test, which is to say, they focused on the potential benefits.

Interestingly, this relationship was seen to persist, even if increased dopamine levels were achieved by medication. In other words, dopamine is the molecule by which motivation is regulated in the brain.

Implications

Varying dopamine levels are seen in different individuals. Lower levels make the person risk-averse, unwilling to take risks when it comes to finishing a difficult task, but higher levels reflect in impulsive and active behavior.

Says researcher Andrew Westbrook, "The thoughts that pop into our head, and the amount of time we spend thinking about them, are regulated by this underlying cost-benefit decision-making system. Our brains have been honed to orient us toward the tasks that will have the greatest payoff and the least cost over time."

So which is better? According to the researchers, neither is inherently superior to the right way. Instead, a person with high dopamine could take risks to fulfill difficult tasks even at the cost of the potential reward. Low dopamine people avoid such injuries but could lose out on fulfilling adventurous experiences. Again, dopamine levels keep changing, with things like lack of sleep or a threat causing reduced levels. However, feelings of security and safety could well increase them.

Who, then, ought to take dopamine? Westbrook makes it clear that natural dopamine highs and lows are generally sufficient to guide the choices between alternative actions in a right and fulfilling manner. If the levels are too low for comfort as in ADHD or depression, increasing the dopamine via medication might help. But taking such stimulants recreationally or without a medical indication could actually guide the choice towards a poorer decision.

Westbrook explains: "When you raise dopamine in someone who already has a high dopamine level, every decision seems like it has benefit, which could distract from the real beneficial tasks. People might behave in ways that aren't consistent with their goals, like taking part in impulsive gambling or risky sexual behaviors."

The study could help understand how the cognitive mechanism works to detect the host of conditions that depend on dopamine levels to some extent. The researchers put it very simply: "We want to know, what are the drivers of what changes cognitive ability and function? Our research is focused on carving nature at its joints, so to speak -- disentangling neural and cognitive functions to understand people's different thought processes and evaluate what's best for their needs, whether it's therapy or medication."

Journal reference:

Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work, A. Westbrook, R. van den Bosch, J. I. Määttä, L. Hofmans, D. Papadopetraki, R. Cools, M. J. Frank, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/367/6484/1362