Researchers have found that by switching on a gene that promotes the spread of cancers, they can enhance the regeneration of damaged heart muscle. The study results, published in April 2020 in the journal Nature Communication, could mark the beginning of curative therapy for heart disease.

Heart disease due to congenital or acquired damage to heart muscle is a leading cause of death in most developed countries. Heart muscle damage can be due to lack of oxygen supply as in ischemic heart disease, or due to excessive mechanical stress as in some forms of congenital heart defects and infection-related damage.

There is currently no way to restore the strength of damaged cardiac muscle cells or to replace dead ones. The heart fills up the gaps with scar tissue, which is fibrous rather than muscular. It, therefore, continues to lose contractile power, and the body is correspondingly weakened by the loss of adequate pumping of oxygenated blood.

Heart failure is the result of such ongoing muscle damage, and it can cause severe deterioration of the quality of life, and eventually, death. It affects about 23 million people all over the world each year.

After a single heart attack, when one or more arteries to the heart muscle are blocked, up to a billion contractile heart muscle fibers can be lost, with severe scarring of the heart if the individual survives. "The inability of the heart to regenerate itself is a significant unmet clinical need," says researcher Wilson.

Moreover, with a burgeoning world population and an increasing prevalence of heart disease, the cost of treating patients with heart failure can be expected to surge. This has motivated much research on how to stimulate the heart to repair itself.

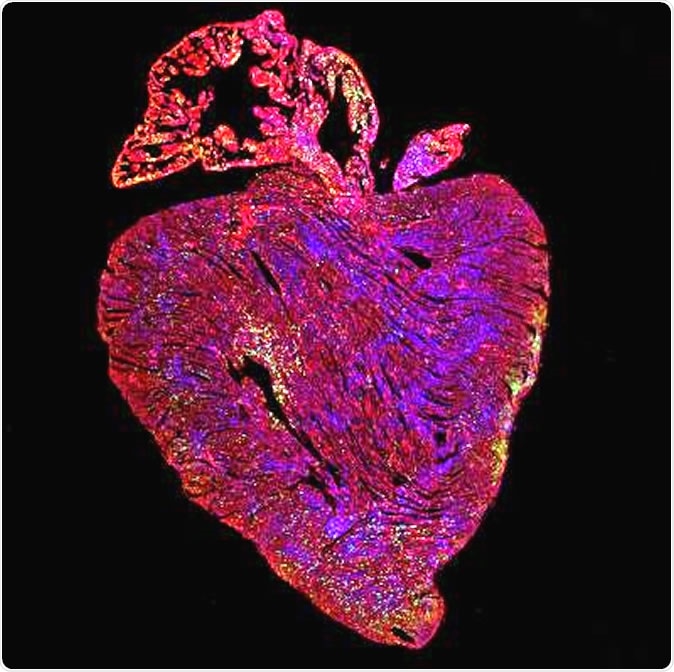

Adult mouse heart after activation of both proteins vital for cell replication. Green shows cells replicating. Image Credit: Cathy Wilson, University of Cambridge

What was the study about?

Mammal cells replicate themselves in order to cause the growth of organs and of the body itself. The mechanism of such replication is contained in the cell cycle. The cell cycle is, therefore, the process through which cells replicate.

This is a strictly regulated process because of the danger of uncontrolled or faulty replication of the genetic matter, the DNA, which could lead to the production of either nonfunctional proteins or to a crazily proliferating cell – the potential origin of a tumor.

The Myc gene is one of many which are known to have a big part in the production of cancer because it is found to be overactive in most cancers. A considerable amount of research has, therefore, been focused on understanding and manipulating this gene.

What did the research show?

The current study looked at the effects of upregulating the expression of the Myc gene in a mouse model. Upregulation means to increase the activity of the gene in terms of protein production. The researchers saw that when the gene was overactive, it led to cancers popping up in many organs, such as the liver and the lungs.

The cancer-promoting effects were due to the replication of very high numbers of cells over the course of just a few days. However, tumor production was not seen in the heart, strange to say.

When they analyzed the matter, they discovered that changes in the level of activity of the Myc gene could only produce a corresponding effect in heart muscle cells if there is enough of another protein called Cyclin T1. The Ccnt1 gene encodes this within the cells. In effect, the Ccnt1 and Myc genes must be co-expressed for the latter to work.

Supplying Cyclin T1, the researchers found, caused the cardiac muscle cells to switch states and enter a regenerative phase. This causes heart cells to replicate, despite the fact that adult heart cells normally do not replicate. The end result? There was "a large increase in the number of heart muscle cells," according to Wilson.

Looking deeper – the role of Ccnt1

The investigators used a next-generation sequencing technology called ChIP to visualize Myc action within the heart cells. They found that Myc triggers the expression of a transcription factor – a protein that binds to the DNA within target cells, switching on gene expression. However, they also observed that even though this binding occurred normally, the transcription factor could not activate the gene, as expected, and thus could not induce the replication of the heart cells. This was due to the deficiency of Cyclin T1.

They then added Cyclin T1 to the heart cells with overactive Myc expression – and cell proliferation began to occur. Wilson says the lack of Cyclin T1 "may be one of the reasons heart cancer is so extremely rare. Now we know what's missing, we can add it and make the cells replicate."

What does the Myc-Cyclin T1 link mean for patients with heart failure?

The researchers want to work on their results to develop a gene-level therapy for heart disease. At the same time, they don't want to trigger heart tumors. Wilson sums up their quest, "We want to use short-term, switchable technologies to turn on Myc and Cyclin T1 in the heart. That way, we won't leave any genetic footprint that might inadvertently lead to cancer formation."

Journal reference:

Bywater, M.J., Burkhart, D.L., Straube, J. et al. Reactivation of Myc transcription in the mouse heart unlocks its proliferative capacity. Nat Commun 11, 1827 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15552-x