Researchers from Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), MIT's research enterprise in Singapore, have discovered a new way to reverse antibiotic resistance in some bacteria using hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

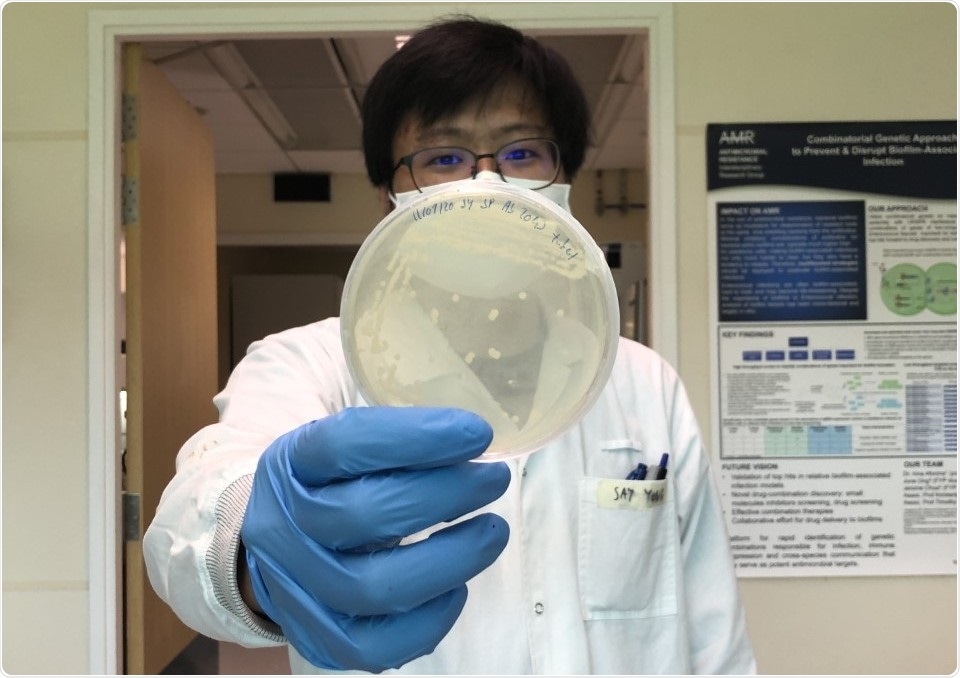

SMART AMR study finds that exposing bacteria to hydrogen sulfide can increase antimicrobial sensitivity in bacteria that do not produce H2S [Credits: Jessie Choo Hui Ling, SMART AMR]

Growing antimicrobial resistance is a major threat for the world with a projected 10 million deaths each year by 2050 if no action is taken. The World Health Organisation also warns that by 2030, drug-resistant diseases could force up to 24 million people into extreme poverty and cause catastrophic damage to the world economy.

In most bacteria studied, the production of endogenous H2S has been shown to cause antibiotic tolerance, so H2S has been speculated as a universal defence mechanism in bacteria against antibiotics.

A team at SMART's Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Interdisciplinary Research Group (IRG) tested that theory by adding H2S releasing compounds to Acinetobacter baumannii - a pathogenic bacteria that does not produce H2S on its own. They found that rather than causing antibiotic tolerance, exogenous H2S sensitized the A. baumannii to multiple antibiotic classes. It was even able to reverse acquired resistance in A. baumannii to gentamicin, a very common antibiotic used to treat several types of infections.

The results of their study, supported by the Singapore National Medical Research Council's Young Investigator Grant, are discussed in a paper titled "Hydrogen sulfide sensitizes Acinetobacter baumannii to killing by antibiotics" published in the prestigious journal Frontiers in Microbiology.

Until now, hydrogen sulfide was regarded as a universal bacterial defense against antibiotics. This is a very exciting discovery because we are the first to show that H2S can, in fact, improve sensitivity to antibiotics and even reverse antibiotic resistance in bacteria that do not naturally produce the agent."

Dr Wilfried Moreira, Corresponding Author of the Paper and Principal Investigator at SMART's AMR IRG

While the study focused on the effects of exogenous H2S on A. baumannii, the scientists believe the results will be mimicked in all bacteria that do not naturally produce H2S.

Acinetobacter baumannii is a critically important antibiotic-resistant pathogen that poses a huge threat to human health. Our research has found a way to make the deadly bacteria and others like it more sensitive to antibiotics, and can provide a breakthrough in treating many drug-resistant infections."

Say Yong Ng, Lead Author of the Paper and Laboratory Technologist at SMART AMR

The team plans to conduct further studies to validate these exciting findings in pre-clinical models of infection, as well as extending them to other bacteria that do not produce H2S.

Source:

Journal reference:

Ng, S.Y., et al. (2020) Hydrogen Sulfide Sensitizes Acinetobacter baumannii to Killing by Antibiotics. Frontiers in Microbiology. doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01875.