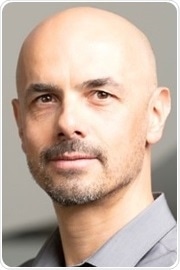

Hello, and thank you for having me. I am Emmanuel Stamatakis, I am a Professor of physical activity, lifestyle, and population health at the University of Sydney. I have been researching the health effects of physical activity and exercise for over 20 years, our new study represents the evolution of this research program, where we examine the interplay of physical activity and other aspects of lifestyle. It made a lot of sense to us to invest in sleep research as both physical activity and sleep are “time-dependent”, that is they both occupy parts of the same 24-hour cycle.

Both physical activity and sleep are critical for good health. Sadly, there are ongoing pandemics of physical inactivity and poor sleep in our society and this is causing huge disease burden and significant healthcare costs.

We also know that sleep and physical activity influence each other, for example, regular physical activity can improve sleep quality, and a good night’s sleep energizes people and makes them more likely to exercise. But we know very little about the combined health effects of these two key aspects of our lifestyle.

Sleep. Image Credit: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock.com

Research into the impact of different variables on our health is extremely important. Why is this especially important in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic?

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused havoc in people’s lives across the globe; in relation to poor sleep and physical inactivity, it has made a bad situation worse. Lockdown restrictions, difficulties in accessing green space and getting outdoors, heightened anxiety and depression, all impact negatively both behaviors.

Understanding the combined health effects of sleep and physical activity may help us understand how to put together programs to help people both cope and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis.

How does physical inactivity and poor sleep increase your risk of cardiovascular disease and death?

Poor sleep and physical inactivity seem to work on the same cardiovascular and metabolic pathways. For example, short sleep and physical inactivity cause endocrine and metabolic dysfunction, increase systemic inflammation and cause stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system which comes with psychological as well as cardiovascular consequences.

Conversely, regular physical activity works on the same pathways as poor sleep but in the opposite direction e.g. regular physical activity improves metabolic function and reduces inflammation. This may partly explain our results; in other words, sufficient physical activity may help neutralize some of the health consequences of poor sleep.

Can you describe how you carried out your latest research into physical activity, sleep, and health?

This study was part of our UK Biobank research program and part of the PhD program of our student Bo-Huei-Huang, first author of the published paper. The UK Biobank recruited almost half a million adults aged 37-73 years back in 2006-2010, who were followed up 2020. At the end of the end of the follow up period we calculated death rates and classified cardiovascular and cancer-related causes of death of the 380,055 participants who were included in our study. Participants reported their leisure-time physical activity and five aspects of their sleep: sleep duration, insomnia, snoring, daytime sleepiness, and sleep chronotype.

We grouped people based on their sleep behavior into healthy, intermediate, or poor. We categorized people's level of physical activity based on [the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. People who met the upper bounds of the guidelines did 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week, or 150 minutes of vigorous exercise, or a combination of both.

Those who met the lower bound did 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week, or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise, or a combination. We then calculated the death risk for each combination of physical activity and sleep, while taking statistically into account any characteristics the comparison groups differed.

Physical Activity. Image Credit: Olena Yakobchuk/Shutterstock.com

What did you discover?

We found that physical inactivity seems to amplify the health risks of poor sleep patterns synergistically, i.e. the mortality risk from physical inactivity and poor sleep combined was much larger than the sum of the separate risk of poor sleep alone plus physical inactivity alone.

Conversely, being physically active (doing at least 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week) seemed to counter most of the premature risks of poor sleep patterns.

What are some of the limitations associated with this observational study?

With observational studies, it is difficult to establish causality with very high certainty. However, we modeled the data and took statistical measures to minimize the chance that the associations we found were due to biases or confounding.

Another limitation is that we relied on questionnaire-based measurements of sleep and physical activity.

What advice would you give to people to help reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease and death?

The challenge with poor sleep patterns is that they are, to a large extend, involuntary. While some aspects of sleep involve conscious decisions (e.g. what time we go to bed), some others are out of our control, e.g. nobody decides to have insomnia or daytime sleepiness. For sleep, my advice would be limited to ensuring adequate amounts of sleep, 7-8 hours for most people, and to avoid screens for a few hours prior to going to bed.

With physical activity, things are more within our control. For people who move very little in general, I would advise them to introduce small amounts of physical activity (10-15 minutes per day, for example) that can comfortably fit into their daily routine, and work towards 25-30 minutes per day overtime. Any activity is fine, as long as they enjoy it and can comfortably fit it in their daily routine in the long term; activities that get them at least slightly out of breath are best.

Physical activity improves sleep quality, so incorporating some regular activity in their daily routine not only they will offer people the direct cardiovascular health benefits of physical activity/exercise but may also help them normalize some aspects of their sleep. Which, in turn, may make them more energetic and motivated to exercise the day after.

Do you believe that with continued awareness into the health problems associated with poor sleep and physical inactivity, we could potentially reduce the number of people dying each year?

Public awareness is one part of the solution only, it will certainly help some and will save some lives. But awareness alone won’t solve the problem. Both physical inactivity and poor sleep are societal, political as well as individual health problems. To solve them fully we will have to seriously re-examine some basic assumptions that underpin our society, economy, relationship with technology, and even politics.

For example, the sharp rise in sleep problems has been partly caused by the anxieties the highly competitive dominant economic systems create and the rapid invasion of screen-based modern technology into our lives. Physical inactivity is an environmental and socioeconomic problem to a large extend. How can people be physically active if they live in car-dominated communities with no green space, where walking and cycling is too dangerous and exercise facilities are not accessible and/or unaffordable?

Cardiovascular Health. Image Credit: Stokkete/Shutterstock.com

What more can governments and organizations do to help raise awareness for the risks associated with poor sleep and little physical activity?

Public health campaigns, such as online and print media campaigns, to promote physical activity and healthy sleep habits could be a great start, as part of a serious long-term strategy that will involve political and budgetary commitment.

Governments that are serious about these causes and the health of their citizens, in general, will need to form partnerships with many sectors and the civil society to come up with a long term strategy to e.g. improve active and public transportation, discourage the use of private cars, build more cycle lanes. Such “upstream” actions will help masses of people become more physically active without even directly trying to do so. In other words, increased physical activity will be a co-benefit of such measures.

The other thing that Governments can do is ensure that medical and other health professionals are equipped and well trained to provide physical activity and sleep behavior modification support to their patients. Most health professionals are not confident and/or skilled. Most medical schools, for example, do not even teach students the official physical activity guidelines.

On average, medical students have 4 hours of lectures on physical activity and diet across their degree, but over 100 hours of pharmacology and related content. What do you think will they prescribe as practitioners to patients who suffer from lifestyle-related diseases?

What are the next steps in your research?

We are leading a large program of research involving collaborators from over 10 countries, the main aim of the program is to understand the combined effects of wearable sensor-measured physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep on cardiovascular health.

Where can readers find more information?

BJSM study: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2021/05/25/bjsports-2021-104046

Some other highlights from this program of research:

About Professor Emmanuel Stamatakis

Emmanuel is a Professor of physical activity, lifestyle, and population health; a National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership 2 Fellow; and a Theme Leader for physical activity and exercise at Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Bristol in 2003 and did a post-doctoral in epidemiology at University College London.

He joined the University of Sydney in 2014 where he currently leads a research program on the health effects of physical activity, sleep, and other lifestyle health behaviors. He has published over 300 peer-reviewed studies and he was named in Clarivate’s Highly Cited Researchers list in 2019 and 2020 (top 0.1% most cited researchers).

Emmanuel co-chaired WHO’s 2020 Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines Development Group, and chaired the adult physical activity recommendations sub-committee. He is a Senior Adviser to the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BMJ). His work has been featured broadly in the media. e.g. since 2015, it has attracted over 7,000 online articles and over 100 TV and radio interviews. He has supervised over 20 research students to completion.