Smoking in pregnancy has been repeatedly reported to be associated with low birth weight and premature birth for more than 20 years. Despite this, France has among the highest maternal active and passive smoking rates in Europe, accompanied by a rising number of early and light babies.

In a new paper, researchers examined existing literature to assess how smoking during pregnancy affects prematurity and low birth weight rates and whether tobacco control policies have been of any use in curbing these adverse outcomes.

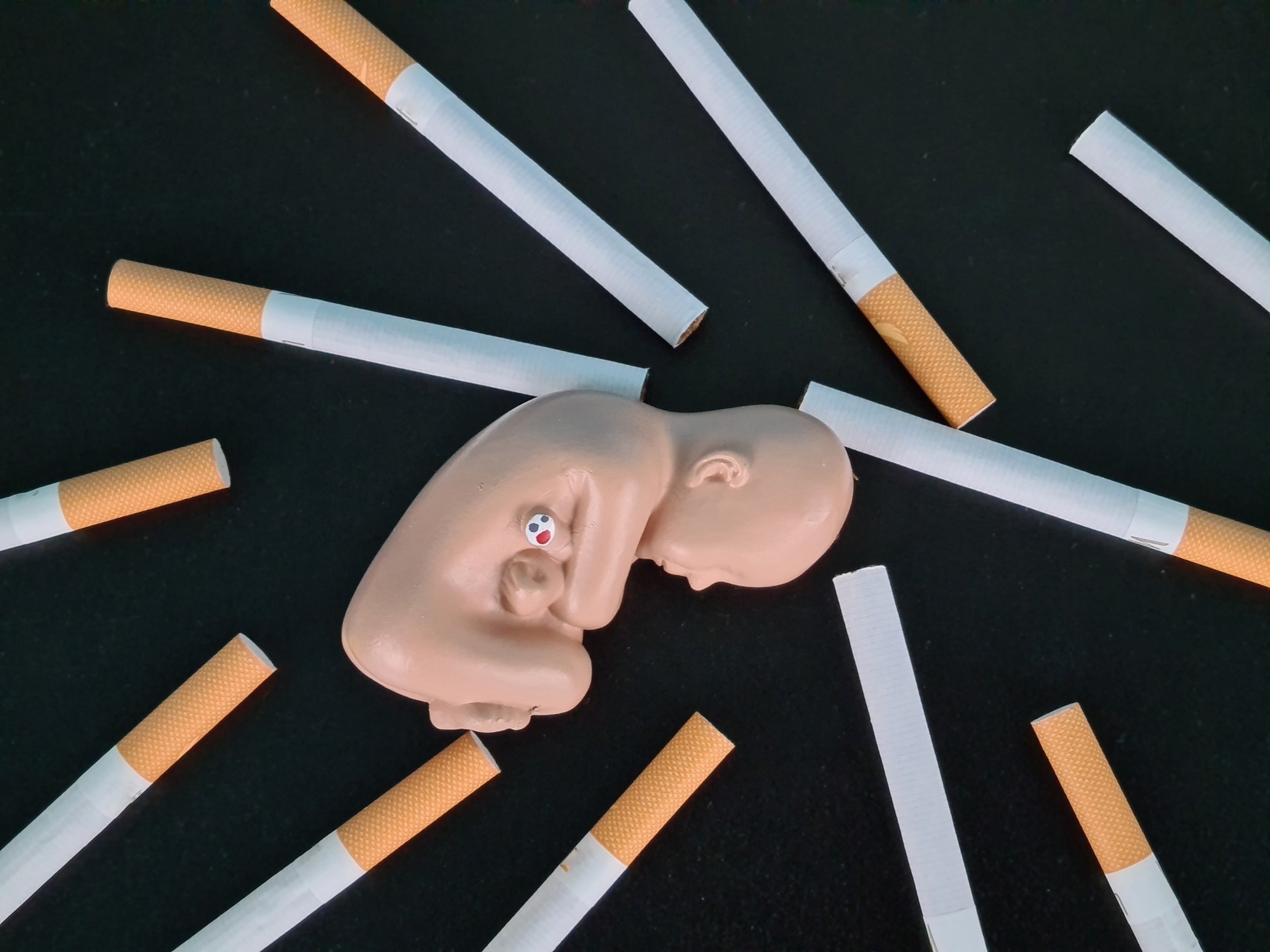

Study: Active or passive maternal smoking increases the risk of low birth weight or preterm delivery: Benefits of cessation and tobacco control policies. Image Credit: NMK-Studio / Shutterstock

Study: Active or passive maternal smoking increases the risk of low birth weight or preterm delivery: Benefits of cessation and tobacco control policies. Image Credit: NMK-Studio / Shutterstock

Introduction

In France, over a quarter of women smoke before conception, with well over one in seven found to smoke even during the third trimester of pregnancy. “The burden of disease from tobacco smoke exposure is very heavy, and among the heaviest burdens are those affecting infants.”

The study, published in the journal Tobacco Induced Diseases, was planned to be a narrative review covering articles on this topic published over the last two decades.

What did the study show?

Active vs. passive smoking

The review found that, as expected, both active and passive smoking were linked to a higher risk of low birth weight as well as preterm delivery.

The impact of smoking was assessed based on fetal exposure, measured in terms of expired carbon dioxide (CO2). Active smoking showed a dose-dependent association with both outcomes.

In most cases, passive smoking was caused by a smoker living in the house, usually the spouse. Nicotine levels in the maternal hair provide an objective measure of exposure to passive smoke.

Smoking reduces birth weight

At 3 ppm or more, the birth weight decreased by approximately 300 g, compared to less than 3 ppm. Earlier research by the authors of the current paper showed that at 6-10 ppm, the birth weight was reduced by a mean of 350 g, vs the birth weight when the exhaled CO2 was 5 ppm. At 20 ppm, the mean decrease in birth weight was almost 800 g.

These findings have been confirmed by the discovery of a linear association between the number of cigarettes smoked and the drop in birth weight at about 27g per cigarette during the third trimester.

Low birth weight (LBW) is defined as a birth weight below 2500 g. A major cause of LBW is fetal growth restriction (FGR), resulting in babies who are small for gestational age (SGA).

FGR has been linked to maternal smoking, considered to be among the top reasons and the most easily fixed cause of FGR. In almost all studies, smoking doubles the risk of FGR and quadruples it in severely obese pregnant women compared to non-smokers.

While pre-eclampsia rates are lower among smokers, those smokers who do develop this condition are at higher risk for LBW compared to non-smokers with pre-eclampsia. The use of cannabis with tobacco as a remedy for nausea increases the risk of LBW further.

Smoking increases prematurity risk

The risk of preterm delivery increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day, with the increase being over a quarter above the baseline risk. With high-risk genotypes such as CYP1A1/GSTT1, the risk is increased almost six-fold by smoking and by 60%, even among low-risk genotypes.

In addition to the dose-response relationship between preterm delivery and smoking in pregnancy, a cause-effect link is suggested by the stability of this association over multiple studies and populations, the effect of duration on the risk, and the pre-existing associations.

After adjusting for sociodemographic factors, the risk of preterm birth has been reported to be almost a fifth higher if smoking was present in the second trimester and by almost three-quarters if the mother smokes throughout pregnancy. In addition, smokers have increased odds of bacterial vaginosis, and with ruptured membranes before active labor begins, these factors mediate the risk of preterm delivery.

With passive smoking, the impact on the fetus depended on the level of exposure to smoke, with the risk being doubled or tripled with a smoking spouse, depending on the ambient air pollution. When nicotine was present in maternal hair at 4 μg/g or more, the risk of preterm birth was increased six-fold, or when the spouse smokes over 20 cigarettes a day.

“These results show the necessity of obtaining smoking information from both parents to evaluate the real adverse effect of passive smoking during pregnancy.”

Does smoking cessation in pregnancy help?

Growth restriction was reduced following smoking cessation. If mothers stopped smoking during the first trimester, the birth weight resembled that of babies born to non-smokers. Even when delayed as late as the third trimester, quitting was associated with reduced risks of preterm delivery and low birth weight.

When professionals were involved in promoting smoking cessation in pregnancy, preterm birth rates dropped by over 80$ and LBW rates by the same degree. The rates of quitting went up by almost half. If spouses continued to smoke, the fetus continued to be at risk for FGR, while mothers were at nine-fold higher risk for continued tobacco use.

This highlights the need to target both parents during smoking cessation programs, especially since prematurity is a major cause of death in young children and of lifelong or prolonged disability in children and teenagers. This “represents for the child both a major health inequality and a flagrant injustice.”

“Smoking parents, being the main source of the child’s exposure to tobacco smoke, by quitting smoking will save years of quality of life and economize in very high healthcare expenses.”

Do tobacco control policies help?

Several articles that examined the benefits of policies restricting tobacco use confirmed their utility in bringing about a significant decline in maternal smoking rates, coupled with marked drops in prematurity. Such policies include prohibiting smoking in public places, smoke-free laws, increasing the minimum legal age for cigarette purchase, and higher taxes on tobacco products.

The resulting drop in passive smoking significantly contributes to better fetal health.

The WHO recommends MPOWER policies (Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies; Protect people from tobacco smoke; Offer help to quit tobacco use; Warn about the dangers of tobacco; Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; and Raise taxes on tobacco).

Nicotine replacement therapy and other tools to mitigate withdrawal symptoms, legislation as outlined above, and educational campaigns in the media are to be coupled with supportive, motivational, and educational approaches to facilitate quitting smoking during prenatal appointments.

What are the implications?

“There is sufficient evidence to infer a causal link between active or passive maternal smoking and low birth weight or preterm delivery. This causal link is compelling and sufficient to justify intensifying efforts to promote rapid progress in tobacco control policies.”

Protecting the fetus from smoke-related consequences is, therefore to be considered as a fundamental human right of the child. Accordingly, all possible means should be pressed into securing this right to the fetus.