Erin McKenney: I am an Assistant Professor and Director of Undergraduate Programs for the Department of Applied Ecology at North Carolina State University. I study how microbial communities form over time and how they adapt to their environments in guts and fermented foods. Across animal and food systems, I have partnered with citizen scientists to engage and empower people of all ages and backgrounds worldwide.

Amanda Hale: I am a Forensic Anthropologist, SNA International for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA); Ph.D. Candidate, North Carolina State University. Before my current position, I taught undergraduate human and animal anatomy labs for ten years. My research is largely interdisciplinary, with my specialty in forensic anthropology focused on human decomposition and human skeletal variation. Currently, my focus is on casework involving human remains, emphasizing human identification and aspects of the biological profile.

What was previously known about the variation in human gut anatomy, and how much attention has this particular area of study received in recent years?

Hale: Variation has been lauded in the biological sciences since the 1800s, but most studies on gut variation after 1885 have focused on the average or the “norm.”

Morphological variations in humans are commonplace and thus could seem unimportant. Why are variations in gastrointestinal morphology significant?

Hale: All morphological variation is important. I think that is the larger message here; in modern anatomical research, there has been a lack of interest in morphological variation within species for over a century in terms of its effect on medical issues, and this reminds us that it has the potential to have a more significant impact on physiology than previously assumed.

Image Credit: Explode/Shutterstock.com

Could you briefly describe how you conducted your research and highlight your main findings?

Hale: In the initial stages, myself and Colleen Grant recognized that in trying to teach anatomy to undergraduate students, we didn’t have a curriculum that demonstrated variation firsthand, even though in biology, variation is the key to almost everything. Second, we do a ton of dissections in anatomy labs worldwide, but it is usually to illustrate what structures SHOULD look like and not the range of what they CAN look like. Then, we thought, is that true? Is there a way to institute a new curriculum that allows students to contribute to the body of data we need to understand this question?

Our research in this study had a few goals: 1) could this curriculum be meaningfully incorporated into the laboratory classroom? 2) could students collect accurate and valuable data to understand gut variation across species? 3) is this variation significant?

McKenney: Amanda Hale and Colleen Grant initially revised a Zoology dissection lab at NC State University to engage undergraduate students in comparative analysis of gut morphology across animals with different feeding strategies. After joining Rob Dunn’s lab as a postdoc in 2017, I connected with Roxy Larsen (who taught human anatomy labs at Duke University then) to gain access to human cadavers, which Amanda and I measured in 2018 with Janiaya Anderson’s help.

Overall we found less variation in frogs, rats, and pigs than in humans. We think this is because the animals reared in captivity are fed standard diets, whereas humans tend to eat whatever they want. Within humans, we found that females have consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males.

In recent years, the gut has been well-known as an organ system with significant impacts on human health. How could your findings influence the understanding of what is driving a range of health-related issues?

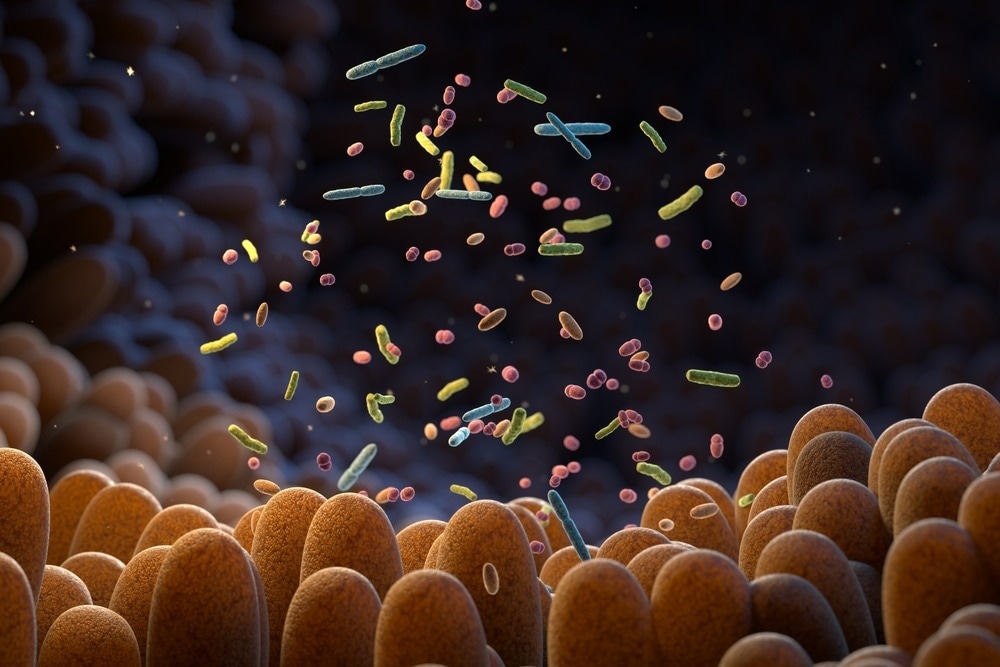

McKenney: The gut hosts the gut microbiome, which contributes to host health through fiber fermentation (or the production of other byproducts when fiber is scarce). Fiber fermentation products (short-chain fatty acids) help satisfy host energy requirements; and also increase feelings of satiety, promote gut development, and are anti-inflammatory (especially butyrate) – meaning they can prevent the development of colon cancer. Regarding the gut-brain axis, microbes also indirectly influence host mood and behaviors (via short-chain fatty acids and other fermentation products) and directly (through physical interaction with dendrite-like cells in the gut).

Hale: It raises the value of the question, “Is morphological variation in the gut contributing to the range of health-related issues?”

Similarly, the gut microbiome has been hitting the headlines for its implications in both physical and mental health. How may morphological variation impact our study and understanding of the gut microbiome?

McKenney: Different morphologies may support different diversity of microbes and provide more (or less) time for microbial fermentation and absorption of the products of fermentation (which contribute to host energy requirements and also provide other health benefits like anti-inflammatory properties).

Image Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

Apart from informing the future of anatomical and medical understanding, what do your findings tell us about the past and the evolution of the human gut?

Larsen: Something has changed, especially in Western diets. We tend to remove all nutrients from foods (to increase production/supply/growth of different foods) and then provide supplements to add back what has been removed

McKenney: The net nutritional composition might remain the same when we process and supplement foods. However, a food more easily digested by humans (or other animals) leaves fewer nutrients for microbes to ferment. That means we’re not providing for the same broad diversity of fiber-fermenting microbes. By eating more easily digested foods, we might be selecting for more opportunistic or competitive microbes.

Hale: At the most basic level, it tells us that there is a reason for that variation and that there are gut morphologies that could be selected upon as diets have changed and as they continue to change in the future. As it pertains to our significant findings for the small intestine between males and females, it emphasizes that other systems (e.g., the gut) possibly evolved to support female reproduction.

As the medical field moves toward individualized medicine to improve patient outcomes and overall health and well-being, how important is teaching anatomical variation to medical students?

Larsen: Students and medical doctors don’t need to know all of the variations, but the variations can be the underlying reason for some of the diseases/disorders we see, More research is needed, and a “typical” body plan or “default” can be a guide but should not be the only version taught

McKenney: I imagine it would be incredibly useful for students to understand that we all differ (sometimes slightly, sometimes more dramatically), and that those differences might change how a doctor approaches a surgery or how disease manifests.

What is next for you and your research?

McKenney: I would love to partner with hunters to measure the guts of different wildlife species! I also hope that medical students might collect and compare their measurements to continue raising awareness and appreciation of variation.

Hale: Hopefully, to raise awareness of the curriculum and build a larger body of data to investigate the points raised in our paper more thoroughly.

Where can readers find more information?

- A Diversity of Guts – protocol developed by co-authors Amanda Hale and Colleen Grant to engage high school and university students in collecting gut measurements during dissection labs.

About Roxanne Larsen

Education and research are integral to my professional life. I conduct research in the scholarship of teaching and learning and the basic sciences.  My basic science research is focused on bats in North and South America, as well as protein misfolding involved in neurodegeneration.

My basic science research is focused on bats in North and South America, as well as protein misfolding involved in neurodegeneration.

About Erin McKenney

My rese arch incorporates microbial ecology, nutrition, and comparative gut morphology to investigate novel questions using perfect, unusual systems. For over a decade I have investigated evolutionary adaptation across scales and species, between non-human primates and rogue (herbivorous) carnivores and their gut microbes. More recently, I have engaged the public, particularly students, to study the microbes in sourdough starters and other fermented foods.

arch incorporates microbial ecology, nutrition, and comparative gut morphology to investigate novel questions using perfect, unusual systems. For over a decade I have investigated evolutionary adaptation across scales and species, between non-human primates and rogue (herbivorous) carnivores and their gut microbes. More recently, I have engaged the public, particularly students, to study the microbes in sourdough starters and other fermented foods.

In the classroom, I cultivate critical thinking through active learning. Millennial students are not limited by access to content; I focus, instead, on practicing current techniques to collect and analyze novel datasets. By designing my courses around authentic research experiences, I encourage student autonomy and foster practicing scientists.

About Amanda Hale

Experienced anatomy instructor and doctoral candidate in forensic anthropology with a background in osteology, forensic casework, and forensic recovery. Skilled in bone mineral density assessment and scanning, geometric morphometrics, histology, a suite of software programs, professional editing, and public speaking. Strong education professional with a Research Doctorate focused in Biology/Biological Sciences, Ecology, and Evolution from North Carolina State University.

in bone mineral density assessment and scanning, geometric morphometrics, histology, a suite of software programs, professional editing, and public speaking. Strong education professional with a Research Doctorate focused in Biology/Biological Sciences, Ecology, and Evolution from North Carolina State University.