A groundbreaking new scanner developed by scientists at the University of Aberdeen could change the way breast cancer is diagnosed and treated, meaning patients could receive fewer surgeries and more individually-tailored treatments.

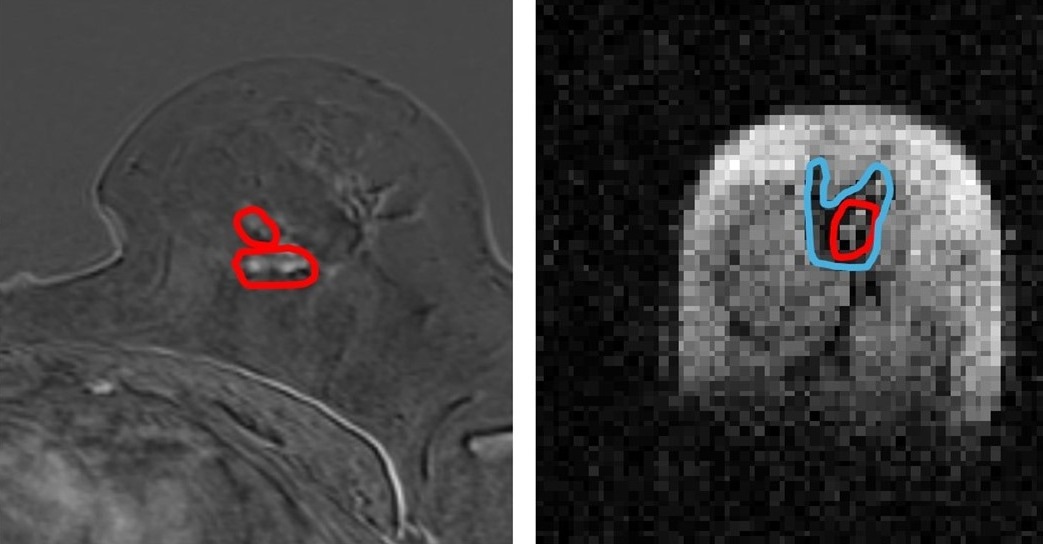

Side by side image of same breast tissue in MRI and FCI. (l) MRI image of breast with cancerous tumours circled in red (r) FCI image of same breast shows same tumour in red with secondary tumour spread in blue. Spread not visible in MRI. The patient had a mixed tumour i.e two different types of tumour and one of them is not visible in MRI. Image Credit: University of Aberdeen

Side by side image of same breast tissue in MRI and FCI. (l) MRI image of breast with cancerous tumours circled in red (r) FCI image of same breast shows same tumour in red with secondary tumour spread in blue. Spread not visible in MRI. The patient had a mixed tumour i.e two different types of tumour and one of them is not visible in MRI. Image Credit: University of Aberdeen

Scientists from the University, in collaboration with NHS Grampian, used a prototype version of the new Field Cycling Imager (FCI) scanner to examine the breast tissue of patients newly diagnosed with cancer. They found that the FCI scanner could distinguish tumor material from healthy tissue with more accuracy than current MRI methods.

This innovation could change the course of treatment for millions of people with cancer. Currently, around 15 percent of women need a second surgery after a lumpectomy as the edges of the tumor may still be involved. This new technique could potentially more accurately outline these tumors and reduce the need for those repeat operations.

This success with breast tissue follows earlier positive outcomes when the prototype was demonstrated to be effective in identifying brain damage due to stroke.

A University of Aberdeen innovation, the FCI scanner follows in the footsteps of the full body MRI scanner, also invented at the University around 50 years ago which has gone on to save millions of lives around the world. The Field Cycling Imager derives from MRI but can work at ultra-low magnetic fields which means it is capable of seeing how organs are affected by diseases in ways that were previously not possible.

While similar to MRI in that MRI uses strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of the inside of the body without touching it - the FCI scanner can vary the strength of the magnetic field during the patient’s scan. This means the FCI acts like multiple scanners in one and can extract multiple different types of information about the tissue.

A further benefit of this new technology is that it can detect tumors without having to inject dye into the body, known as contrast, which has been associated with kidney damage and allergic reactions in some patients.

Dr Lionel Broche, senior Research Fellow in Biomedical Physics and lead researcher in the study said: “We found that images generated from FCI can characterize breast tumors more accurately. This means it could improve the treatment plan for the patients by improving the accuracy of biopsy procedures by better detecting the type and location of tumors, and by reducing repeated surgery so really, the potential impact of this on patients is extraordinary.

“My colleagues in the University of Aberdeen built the world’s first clinical MRI in the 1970s so it is both fitting and exciting that we are making waves again with an entirely new type of MRI called Fast Cycling MRI – FCI.

“This is a truly exciting innovation and as we keep improving the technology for FCI, the potential for clinical applications is limitless.”

Dr Gerald Lip, consultant radiologist in NHS Grampian and co-investigator in the study, has recently been appointed President of the British Society of Breast Radiology.

This data is very promising, and we still need more prospective work, but these results will really support future clinical applications.

We treat between 400 and 500 women with breast cancer in NHS Grampian every year and the potential this technology has to reduce the need for women to return for extra surgery is huge, benefitting them and reducing wait times and operating theatre resource.

We hope it will have a future role in supporting cancer diagnosis and management."

Dr Gerald Lip, consultant radiologist, NHS Grampian

The research is published in Nature Communications Medicine.

Source:

Journal reference:

Mallikourti, V., et al. (2024). Field cycling imaging to characterise breast cancer at low and ultra-low magnetic fields below 0.2 T. Communications Medicine. doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00644-2.