What is Auto-Brewery Syndrome?

Symptoms and diagnosis of ABS

Causes and risk factors

Treatment and management

Case studies and patient experiences

Research and future directions

Conclusion

References

Further reading

What is Auto-Brewery Syndrome?

The rare gut condition known as auto-brewery syndrome (ABS), or gut fermentation syndrome, causes the body to create ethanol through the endogenous fermentation of carbohydrates by microorganisms. Patients with underlying gut issues are more likely to experience it1; these patients commonly report eating a diet high in sugar and carbohydrates and show numerous signs and symptoms of alcohol intoxication while denying alcohol usage1.

Image Credit: Pressmaster/Shutterstock.com

Symptoms and diagnosis of ABS

A systematic review reported the most common signs observed in patients to be slurred speech, fruity breath odor, walking difficulties, episodes of depression, seizures, vomiting, intoxicated feeling, and disorientation2.

An assessment of the patient's medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, stool culture and samples, a carbohydrate challenge test, and endoscopy with biopsies for culture are all included in the comprehensive evaluation of the condition2. Completing a patient's history should include information about alcohol consumption, usage of antibiotics, and unexplained episodes of drunkenness.

Gastrointestinal secretions and biopsies for bacterial and fungal tests can be obtained via an upper and lower GI-tract endoscopy2. Antifungal and antibiotic sensitivity tests can then be performed on these fungi and bacteria. When the carbohydrate challenge test is positive, a causative microorganism has been cultured, and all other possible explanations for the symptoms have been ruled out, the diagnosis of ABS can be made2.

Causes and risk factors

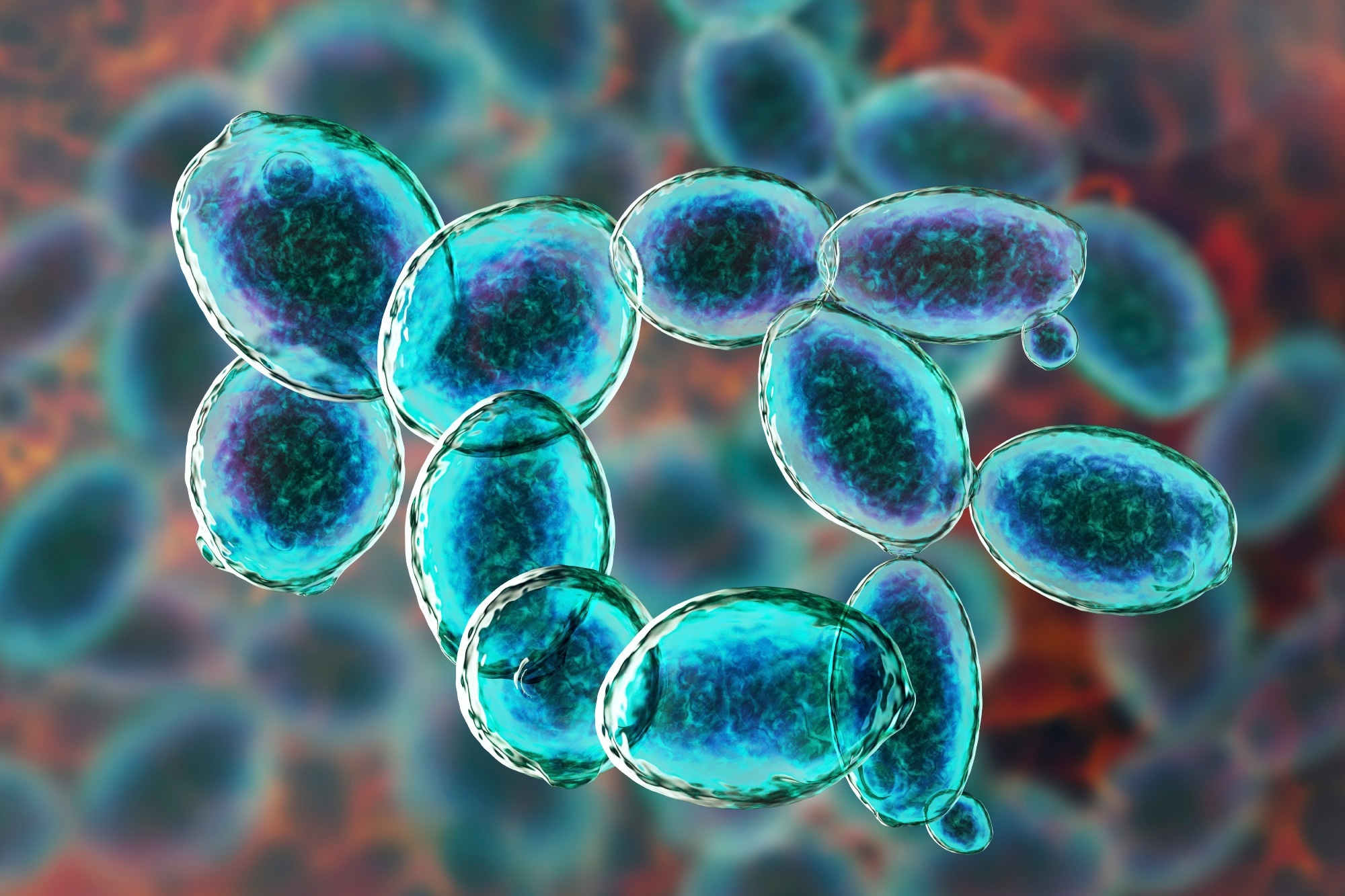

This disorder is known to be caused by fermenting yeasts, specifically Saccharomyces cerevisiae (shown below), S. boulardii, and other strains of Candida, such as C. glabrata, C. albicans, C. kefyr, and C. parapsilosis1. At least one case involving bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumonia3,4 and Enterococcus faecalis4 has also been reported.

Image Credit: fermenting yeasts/Shutterstock.com

ABS is more common in people with diseases where the body produces more ethanol—such as diabetes, obesity, short bowel syndrome, and Crohn's disease—or conditions where the body produces less ethanol—such as those receiving long-term antibiotics, liver failure, and genetic deficiencies of liver enzymes5,6.

Research comparing individuals with and without ABS shows that patients with ABS are more likely to have food sensitivities, poorer overall health, and diarrhea7. They also tend to have fewer bowel movements, get less sleep, and have a higher presence of non-food allergies8.

Treatment and management

Immediate care of the patient should focus on the treatment of acute alcohol poisoning. Drug therapy depends on the causative microorganism involved. The majority of patients need to be prescribed one or more azoles or polyenes1. An antibiotic or an echinocandin is required for rare or resistant bacteria.

Changing one's diet to one that is strong in protein and low in carbohydrates is crucial for treating auto-brewery syndrome till symptoms go away. The fermentation of sugar produces alcohol; therefore, removing both simple and complex sugars from the diet will reduce the amount of alcohol produced in the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts1.

Several documented cases in the literature were resolved without the need for medication therapy if the dietary recommendations were followed9. Although its effectiveness in treating this syndrome has not yet been investigated, probiotics like Lactobacillus are also used in certain situations4.

Auto-Brewery Syndrome: The World’s Weirdest Happy Hour

Case studies and patient experiences

Saverimuttu et al. (2019) reported a case of a 45-year-old male Italian-American with a body mass index (BMI) of 35 who was suffering from hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. After a nasal septal surgery in August 2015, he received antibiotics and steroids as treatment. He had spent the last twenty years without drinking.

In October 2015, two months after starting the antibiotic course, he started having frequent seizures and seemed drunk. The patient emphasized, along with his spouse, that he never drank alcohol. His wife had also noticed that he had glassy eyes, slurred speech, and an alcoholic stench on his breath during this time. He was having fits of incoherent speech, frequent falls, and spells of poor coordination4.

A year after initial symptoms, the patient underwent dental surgery and was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, which worsened his symptoms, mimicking alcohol intoxication. Despite no alcohol consumption, his blood alcohol levels increased, leading to repeated misdiagnoses and inadequate treatment. Eventually, a supervised glucose challenge test revealed fluctuating ethanol levels, confirming auto-brewery syndrome4.

His auto-brewery syndrome diagnosis came approximately a year and a half after he first had symptoms. The patient was put on a low-carb, high-protein diet at first. In addition, a pure Lactobacillus probiotic and a three-week course of oral fluconazole at a dose of 100 mg each were administered to him. He was then started on many doses of fluconazole for the duration of his therapy. Since 2015, the patient has missed almost 725 hours of work due to illness and disability. However, his story ends positively, as he has returned to work and is leading a regular life while using antibiotics with caution and avoiding all forms of yeast exposure4.

Malik et al. (2019) reported a previously healthy 46-year-old man sought help for auto-brewery syndrome after experiencing significant mental changes and depression following antibiotic therapy for a thumb injury. Despite abstaining from alcohol, he showed elevated blood alcohol levels and symptoms of intoxication. Initial treatment with fluconazole and nystatin led to temporary improvement, but symptoms returned.

Further testing revealed Candida species in his gut, and he was treated with itraconazole and then micafungin. Following treatment, no fungal growth was detected, and his condition improved with the addition of probiotics and a carbohydrate-free diet. Gradually reintroducing carbohydrates showed no relapse, and he remains asymptomatic 1.5 years later, having resumed a normal lifestyle while monitoring his breath alcohol levels. This case highlights the complexity of diagnosing and treating ABS and the importance of comprehensive, ongoing management 10.

Research and future directions

Numerous cases of ABS have been documented in recent years, but more research is needed to fully understand the mechanism, diagnosis, and appropriate course of treatment. It has lately been hypothesized that ABS might be an underdiagnosed medical illness, even though it is rarely reported10. To ascertain the actual frequency of ABS, create uniform diagnostic standards, and look into the best course of therapy, more study is needed. We can comprehend the intricate relationships between antibiotics, gut microorganisms, and ABS development with the further improvement of microbiome research11.

Conclusion

Auto-brewery syndrome (ABS) is a rare but significant condition where the body produces ethanol internally, leading to symptoms of intoxication. Diagnosis involves a thorough evaluation, including medical history, laboratory tests, and endoscopy. Effective management often requires a combination of antifungal or antibiotic therapy and dietary changes. Research suggests ABS might be underdiagnosed, necessitating further studies to establish standard diagnostic criteria and optimal treatments. Advances in microbiome research will be crucial in understanding and managing this complex syndrome.

References

- Painter, K., Cordell, B. J., & Sticco, K. L. (2023). Auto-Brewery Syndrome. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Bayoumy, A. B., Mulder, C. J. J., Mol, J. J., & Tushuizen, M. E. (2021). Gut fermentation syndrome: A systematic review of case reports. United European gastroenterology journal, 9(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/ueg2.12062

- Yuan, J., Chen, C., Cui, J., Lu, J., Yan, C., Wei, X., Zhao, X., Li, N., Li, S., Xue, G., Cheng, W., Li, B., Li, H., Lin, W., Tian, C., Zhao, J., Han, J., An, D., Zhang, Q., Wei, H., … Liu, D. (2019). Fatty Liver Disease Caused by High-Alcohol-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell metabolism, 30(6), 1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.006

- Saverimuttu, J., Malik, F., Arulthasan, M., & Wickremesinghe, P. (2019). A Case of Auto-brewery Syndrome Treated with Micafungin. Cureus, 11(10), e5904. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.5904

- Kubiak-Tomaszewska, G., Tomaszewski, P., Pachecka, J., Struga, M., Olejarz, W., Mielczarek-Puta, M., & Nowicka, G. (2020). Molecular mechanisms of ethanol biotransformation: enzymes of oxidative and nonoxidative metabolic pathways in human. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems, 50(10), 1180–1201. https://doi.org/10.1080/00498254.2020.1761571

- Nair, S., Cope, K., Risby, T. H., & Diehl, A. M. (2001). Obesity and female gender increase breath ethanol concentration: potential implications for the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The American journal of gastroenterology, 96(4), 1200–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03702.x

- Cordell, B. J., Kanodia, A., & Miller, G. K. (2019). Case-Control Research Study of Auto-Brewery Syndrome. Global advances in health and medicine, 8, 2164956119837566. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956119837566

- Cordell, B., Kanodia, A., & Miller, G. K. (2021). Factors in an Auto-Brewery Syndrome group compared to an American Gut Project group: a case-control study. F1000Research, 10, 457. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.52743.1

- Welch, B. T., Coelho Prabhu, N., Walkoff, L., & Trenkner, S. W. (2016). Auto-brewery Syndrome in the Setting of Long-standing Crohn's Disease: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of Crohn's & colitis, 10(12), 1448–1450. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw098

- Malik, F., Wickremesinghe, P., & Saverimuttu, J. (2019). Case report and literature review of auto-brewery syndrome: probably an underdiagnosed medical condition. BMJ open gastroenterology, 6(1), e000325. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000325

- Paramsothy, J., Gutlapalli, S. D., Ganipineni, V. D. P., Okorie, I. J., Ugwendum, D., Piccione, G., Ducey, J., Kouyate, G., Onana, A., Emmer, L., Arulthasan, V., Otterbeck, P., & Nfonoyim, J. (2023). Understanding Auto-Brewery Syndrome in 2023: A Clinical and Comprehensive Review of a Rare Medical Condition. Cureus, 15(4), e37678. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37678

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 26, 2024