Introduction

Chronopathology

Chronotherapeutics

Conclusion

References

Further reading

Chronobiology is an upcoming field of study that leaves many bewildered as to its scope. This branch of science explores the impact of time on biological systems.

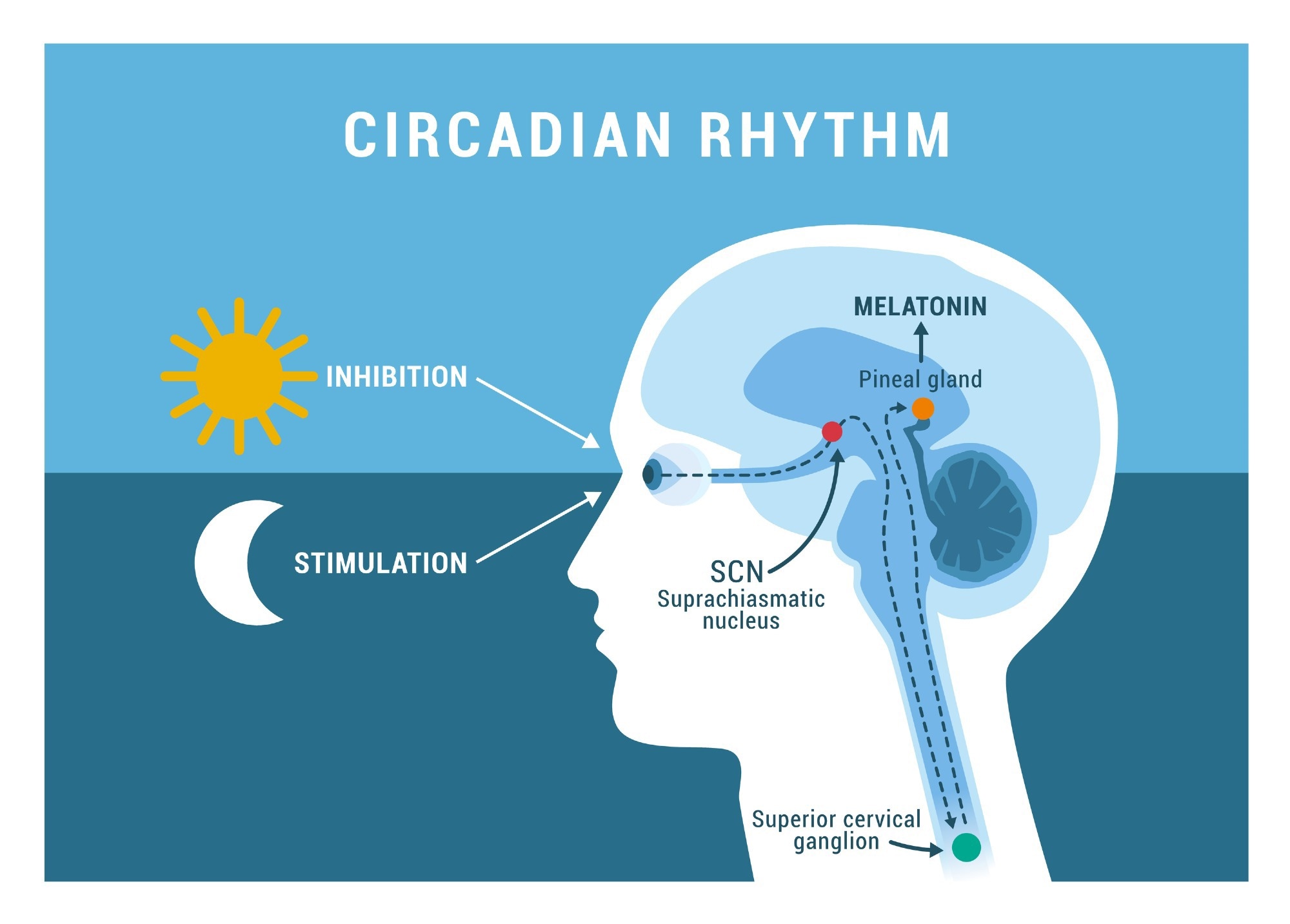

The circadian rhythm. Image Credit: vetre/Shutterstock.com

The circadian rhythm. Image Credit: vetre/Shutterstock.com

Some fascinating aspects of chronobiology include periodicity, or the circadian rhythms in the human body regulated by the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus, which contains the master clock for biological rhythms.

Some of the physiological processes controlled by this clock include the core body temperature, the rest-activity cycle, physiological and behavioral functions, mood, and psychomotor functions. The biological clock depends on light exposure to set itself to the external solar day/night cycle.

Mood disorders including depression, bipolar depression, and seasonal affective disorder (SAD) have been found to be linked to abnormalities in the circadian rhythms. Both light and melatonin affect these rhythms, and methods to artificially alter them have been identified.

This synchronization of body processes with external time is a means to optimize survival odds. It helps the organism prepare for 24-hour rhythms, with the varying availability of light, heat, and food, for instance. It also pushes apart mutually incompatible processes such as feeding from physical work and sleeping from waking.

Circadian rhythms can be monitored using currently available clinical tools. This type of information could help plan interventions when the body is best adapted to receive them. It could also inform the healthcare team when such rhythms are lost, indicating the onset of critically severe illness.

Individuals have their own chronotypes, that is, naturally preferred waking and sleeping times. These are expressions of the internal rhythms, stretching from morningness to eveningness, that is, people who peak in the first part of the day vs those who wake late and work best in the second part of the day, respectively. Interestingly, these are based on the time of onset of melatonin secretion.

Chronopathology

Researchers have currently been able to identify molecular clocks in various tissues that regulate the function of the body by time. When this synchronization of the body clocks with physiological processes is disrupted, a condition called chronopathology, further clinical deterioration is caused.

Chronopathology is the result of the disruption of the body rhythms. Jet lag is possibly the best-known condition in this category. However, chronic failure to synchronize voluntary activity cycles with the circadian rhythms, as with long-term night shift work, has been associated with multiple disease processes, including sleep disorders, as well as metabolic, cardiovascular and malignant diseases.

Many diseases that fluctuate over time have been found to link to circadian rhythms. For instance, rheumatoid arthritis sufferers experience pain and stiffness mostly in the morning hours because inflammatory cytokines increase over the night. Heart attacks, strokes, and brain bleeds are much more common in the early morning.

Again, asthma and allergic rhinitis symptoms peak during the latter night hours, both because of sleeplessness and altered lung and nasal mucosal characteristics due to circadian rhythms. “Sundowning” in patients with Alzheimer's disease and the “dawn phenomenon” in diabetes patients are both well-known occurrences linked to body rhythms.

Furthermore, blood pressure follows a regular cycle, and therefore blood pressure charts should reflect this reality.

The same is to be expected when lung function tests and skin tests for allergens are carried out at varying times of day, with gross variations when these measurements are performed at different times.

Since patients with critical illness are at higher risk for such disruption, there should be an active effort to restore the harmony of the body with external time and light cues – a so-called ‘chronofitness” goal. Many medical interventions are currently carried out without regard for their effect on body rhythms, or vice versa.

Some studies indicate that eveningness is associated with a higher risk of cardiometabolic disease, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, high body mass index, and sarcopenia. Depression is also more common among evening people.

Knowing an individual’s chronotype may thus help not just to predict the risk of these conditions, but to manipulate the time of exposure to external cues that reset the body clocks, such as light, food, and exercise, so as to best fit them to the natural rhythms.

Mutations of the molecular clock genes that generate cellular rhythms are also known and are associated with sleep disorders. Moreover, these genes have to do with cell division, DNA repair, and multiple metabolic pathways. Thus, several variants of these genes have been found to be associated with the above disorders.

Researchers have referred to an epidemic of environmental circadian rhythm disturbance, as people are unable to fit modern work and social situations around their chronotype. This has been termed ‘social jetlag’.

The circadian rhythm. Image Credit: elenabsl/Shutterstock.com

The circadian rhythm. Image Credit: elenabsl/Shutterstock.com

Chronotherapeutics

Chronotherapeutics is a term coined to denote the administration of an intervention or drug at the right time to ensure the highest chance of its having its physiologically intended effect. This field of study needs to account for the difference in drug absorption, liver metabolism, and excretion through the kidneys, which will determine when the drug would be most effective.

Many drugs have been shown already to fluctuate in their plasma and tissue levels, depending on the time of day. This becomes more important in the case of drugs like antibiotics and steroids, which have a narrow margin of safety but show circadian rhythms in their pharmacological characteristics.

Benzodiazepines are commonly used drugs, yet they accomplish a major phase shift, and should preferably be given at the time when the patient is in the correct circadian phase to absorb the effect of the drug without harm.

The cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin was first shown to be effective in the evening when the target enzyme was most active. This is a prime example of timing drug administration for the time when its target is highly expressed.

Conversely, the drug can be given at the time when its undesirable target is at its nadir, thus lowering the risk of toxicity. More than a hundred such studies have affirmed the importance of chronotherapeutics.

Early data also points to better wound healing and repair mechanisms during the day, which could modulate the time for elective surgery.

Melatonin helps bring peripheral and central clocks into phase and has been taken orally to improve sleep, reduce jet lag, and reduce delirium in critically ill patients. Other drugs are being explored to help treat or reduce the metabolic sequelae of circadian rhythm disruption.

Timed interventions, light therapy, and modifying one’s lifestyle, are valuable adjuvants to optimize the effectiveness of various treatment protocols. In cancer chemotherapy, research suggests that chronotherapy, in the form of circadian-adjusted timing of drug administration, reduced toxicity and improved survival rates in lymphoma patients, particularly among females.

Yet such protocols are slow to move into clinical practice, both because of scientific inertia and practical obstacles such as limited infrastructure for timed chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Similarly, critical care for ill patients benefits from simply providing light cues that match the external day-night variation and reducing noise and interventions that interfere with the normal sleep-wake cycle.

Further research will be required to disentangle the mechanisms underlying the circadian effects of drugs and medical interventions.

What Makes You Tick: Circadian Rhythms

Conclusion

An algorithm called CYCLOPS explored circadian gene expression on a population scale. It demonstrated that the body’s internal clock regulates half of the protein-coding genome, regardless of ethnicity, age or sex.

This also linked thousands of drugs to genes that encoded their target receptors, transporters or metabolizing enzymes, helping to identify the pathway by which circadian rhythms affected drug activity when given at varying times of day.

Circadian medicine has a huge potential to affect drug and intervention efficacy. Hopefully, better-powered trials will show the clear benefits of chronotherapy, transforming current medical treatment to help the majority rather than the minority of patients treated with the most common drugs.

References

- Kramer A et al. (2022). Foundations of circadian medicine. PLOS Biology. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001567.

- Caliyurt O (2017). Role of chronobiology as a transdisciplinary field of research: its applications in treating mood disorders. Balkan Medical Journal. doi: https://www.doi.org/

- McKenna H et al. (2018). Clinical chronobiology: a timely consideration in critical care medicine. Critical care. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2041-x.

- Lee HJ (2023). Importance of Circadian Rhythm in Drug Administration Timing. Chronobiology in medicine. doi: 10.33069/cim.2023.0006.

- Ruben MD et al. (2019). Dosing time matters. Science. doi: 10.1126%2Fscience.aax7621.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023