Sepsis refers to an overwhelming life-threatening systemic response to an infection. When a person becomes infected with a microorganism, the body’s immune cells release small proteins called cytokines as part of the immune response. These cause inflammation but if this response gets out of hand this can lead to poor blood flow, low oxygen levels in organs, low blood pressure resulting in septic shock.

Skip to:

Kotin | Shutterstock

Kotin | Shutterstock

The World Health Organization estimates that sepsis affects more than 30 million people annually causing six million deaths. Sepsis is a particular problem in high in middle and low-income countries. Children are especially vulnerable, with an estimated three million newborns and over one million children affected each year.

What are the signs and symptoms of sepsis?

There are three stages in the development of sepsis.

1. Sepsis

Early sepsis is characterized by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) - tachycardia, tachypnea, fever (over 100.4 F or 38oC) or hypothermia (below 96.8 F or 36oC), and leukopenia or leukocytosis. Other common clinical features at this stage include:

- Shivering

- Disorientation

- Lightheadedness

- Nausea and vomiting

2. Severe sepsis

In the second stage, severe sepsis sets in, with features such as:

- Coagulopathy

- Endothelial injury

- High levels of inflammatory cytokines

- Critical neutropenia

- Tissue necrosis

- Dysregulation of metabolism

This leads to dysfunction of vital organs like the liver, lungs, heart and kidneys.

3. Septic shock

Finally, the individual goes into septic shock, characterized by a rapid decline in arterial blood pressure. This drop in pressure means that the organs do not receive enough oxygen to function and approximately half of patients treated in hospital intensive care units do not survive with this condition.

What are the causes of sepsis?

Potentially sepsis can be caused by any type of infectious pathogen that invades the body or toxins excreted by the pathogen. The infection can be limited to a specific organ or it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. The most common microorganisms that cause sepsis include: Streptococcus pneumoniae, the influenza virus, and bacteria that cause urinary and gastrointestinal infections.

Bacteria may be described as Gram-negative or Gram-positive, depending on whether they take up the Gram stain. The former include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Their cell walls contain toxic chemicals called endotoxins, chemically composed of fats and carbohydrates called lipopolysaccharides (LPS).

When these cells are dying, they release LPS which activate a type of immune cell called a macrophages and set off an immune response called the inflammatory cascade. They also cause direct host cell injury and attract many more white cells which release even more cytokines. This stimulates the release of chemicals that widen blood vessels. This results in overwhelming inflammation and septic shock.

On the other hand, Gram-positive pathogens which include Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Enterococcus produce superantigens. These cause septic shock, but in a different way. These peculiar antigens are the strongest known activators of an immune cell called T-lymphocytes, binding up to 20% of these cells, bypassing normal immune mechanisms. The resulting flood of cytokines into the patient’s system results in lethal shock.

Both superantigens and LPS can increase the effect of each other and therefore the severity of inflammation a hundred-fold. Severe infection with influenza, HIV, varicella and other viruses can cause widespread cell death and cytokine release, resulting in severe systemic inflammation. Fungal infections like Candida, Pneumocystis, Histoplasma and Aspergillus may also sometimes cause serious infections, more often in immunocompromised patients.

What happens to the body during sepsis?

In sepsis, the body’s normal immune response triggers a systemic inflammation that injures the host. A simplified description follows:

- Microbial toxins bind to specific immune cell receptors and activate the immune response.

- Cytokines, which cause inflammation are released from the body’s immune cells which then attract even more leukocytes and other immune cells.

- These immune cells and cytokines overwhelm the body in a condition called severe systemic inflammation.

- The very high cytokine levels affect the blood coagulation system, causing clots in the tiny blood vessels of the body (microvascular thrombosis), resulting in hypoperfusion (inadequate blood supply) of the affected organs.

- Tissue death and multi-organ damage occurs.

- Cytokines from damaged cells and immune reactions cause the dilation of blood vessels.

- A combination of these factors causes a lethal fall in arterial blood pressure, cutting off blood and oxygen from vital organs, and causing systemic low blood pressure and collapse.

What are the risk factors for sepsis?

People with preexisting diseases, conditions or life stages that increase the risk of infection and/or impair the body’s immune response are at risk of sepsis. These include:

- Immunocompromised states as with AIDS, diabetes mellitus, chemotherapy, treatment with certain biologics, anti-rejection drugs after organ transplants, following any debilitating illness, or splenectomy

- Extremes of age

- Following major surgery, burns or trauma, and organ transplants

- Septic procedures such as illegal abortions

- Alcoholism

When to suspect sepsis

If two or more features of systemic infection or SIRS are present, immediate medical consultation is strongly advised.

How is sepsis diagnosed?

Sepsis should be suspected if there is evidence of infection with two or more features of SIRS. Alternatively, if the PIRO guidelines are fulfilled, sepsis is suspected. PIRO stands for Predisposition, Infection, Response, and Organ Dysfunction and is a classification system to group patients with sepsis in categories with different outcomes, including mortality rates.

Following a careful history and physical examination, a blood test may be carried out to confirm the diagnosis. Other laboratory tests which may be carried out to determine the type and location of the infection include:

- Rapid tests for common infections (strep throat, influenza, and skin infections)

- Urine or stool testing

- Sputum testing

- Pus culture (if the patient has a wound)

- Coagulation tests to detect coagulopathy due to sepsis

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) study to rule out meningitis

- Imaging tests including computerized tomography (CT), ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning to assess organ dysfunction

- Tests for sepsis biomarkers (not yet routine) include:

- LPS-binding protein

- Procalcitonin test (PCT)

- IL-6 levels

- Strem-1 levels

- suPAR

- multiplex PCR

How is sepsis treated?

When sepsis is suspected, early and appropriate antibiotic therapy is vital, preferably after taking a blood culture.

Continuous monitoring and stabilization of the patient is essential. This involves attention to breathing and organ perfusion, early aggressive fluid resuscitation, and if necessary, oxygen, ventilator support, and dialysis, with steroids and vasopressors. Any detectable source of infection must be treated, including amputation in septic shock.

In early sepsis, antibiotics at home are typically sufficient. With advanced sepsis, hospitalization is necessary, and often intensive medical care, due to the high mortality. New experimental treatments for severe sepsis include stem cell therapy and HMGB1 protein inhibitors.

What is the prognosis of sepsis?

The Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score is used to determine the patient's prognosis in cases of sepsis. Typically, the mortality in severe sepsis and in septic shock is between 20% to 35%, and 40% to 60%, respectively. Many more patients die within a few months, due to inadequately controlled infection, underlying illness, or complications.

What is post-sepsis syndrome?

About 50% of survivors of severe sepsis experience cognitive and physical problems, either short-term or chronic. The post-sepsis syndrome (PSS) may be due to myopathy and neuropathy resulting from the inflammation, tissue ischemia, and ischemic-reperfusion injury to various organs, possibly aggravated by some therapeutic agents and includes:

- Muscle weakness

- Excessive fatigue

- Chest pain

- Anxiety

- Impaired memory

- Cognitive impairment, such as simple arithmetic

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Rehabilitation is essential to promote recovery, which may still take two years or more. It should be initiated early, while in hospital, including physiotherapy for muscle strength, and occupational therapy for functional independence.

Careful follow up is important, as are rest, appropriate exercise and a nutritious diet.

Neonatal sepsis

Neonatal sepsis occurs in babies less than 90 days old, most commonly from meningitis, pneumonia, gastroenteritis or pyelonephritis.

Clinical features of neonatal sepsis

Due to the immature immune response and high mortality for sepsis (>50%), fever above 38 oC in babies requires a high index of suspicion for neonatal sepsis. Babies and young children often show no signs of dangerous infection until they are near collapse, due to their tremendous physiological reserve.

Other signs include:

- Reluctance to feed or drink for over 8 hours

- Repeated vomiting after feeding

- Absence of urine for over 12 hours

- Pallor

- Jaundice

- Lethargy

- Floppiness

- Difficult breathing

- Signs of an infection such as a bulging fontanelle

- Irritability

Risk factors for neonatal sepsis

These include preterm delivery, prolonged (>18 hours) leaking of amniotic fluid before delivery, and chorioamnionitis. Common pathogens include Group B Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Neisseria meingitidis, Salmonella, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Listeria monocytogenes, in addition to herpes simplex, all of which may come from the mother or from the delivery environment.

Treatment of neonatal sepsis

Early and aggressive treatment with antimicrobials within an hour of diagnosing suspected sepsis, with immediate adequate fluid resuscitation, and monitoring as indicated, is vital. Infants must be stabilized in hospital, and thereafter discharged if appropriate. Careful follow up is mandatory.

Treatment of maternal infections, and good environmental hygiene before, during and after childbirth are essential to preventing neonatal sepsis.

Sepsis in children (pediatric sepsis)

Sepsis manifests much later in children than in adults and requires a high index of suspicion. Over half of the mortality occurs within 24 hours of diagnosis. Early and aggressive treatment is vital.

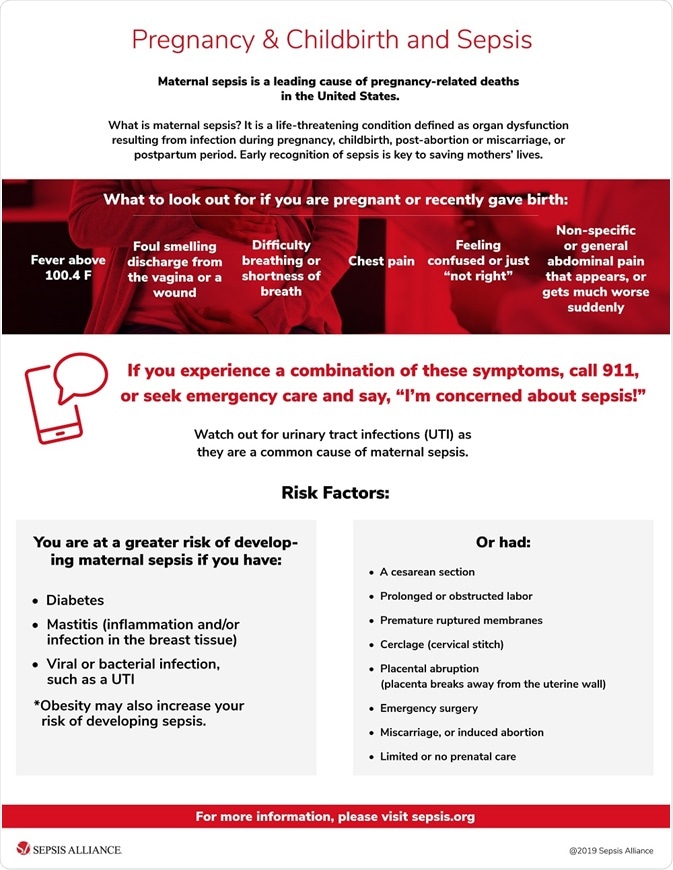

Maternal sepsis

Maternal sepsis refers to severe bacterial infection of the uterus, in pregnancy or soon after childbirth. Symptoms include chills, lower abdominal pain, bleeding and foul discharge from the vagina, dizziness and collapse.

Risk factors include:

- Operative or Cesarean delivery

- Poor hand hygiene

- Prolonged labor

- Early rupture of membranes

- Retained placenta

- Multiple vaginal examinations in labor

Often caused by Group B Streptococcus, maternal sepsis was a leading cause of maternal mortality but is now much rarer, and easily treated with antibiotics. The WHO estimates that one in ten deaths associated with pregnancy and childbirth is still due to maternal sepsis.

An infographic from Sepsis Alliance is provided below.

Sepsis and other conditions

Sepsis and pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), commonly due to S. pneumonia infection, is the most common source of sepsis in adults. Its symptoms include fever with productive cough, sweating, chills, headache and myalgia, and breathing-associated chest pain. Healthcare-associated pneumonia (HAP) may occur as a complication of ICU admission for sepsis.

Early confirmation of lung infection can help avoid misdiagnosis of S. pneumoniae-associated sepsis during the critical early phase of the condition.

People at high risk of developing CAP (the old and the very young, smokers, those with chronic lung disease), should consider pneumococcal vaccines.

Sepsis and E. coli

Infection with some strains of Escherichia coli can lead to sepsis. E.coli infection can occur after contact with an infected person or the consumption of contaminated food or water.

Infection with pathogenic E.coli strains can result in diarrhea, cramping, nausea and vomiting and are commonly described as an important causative agent of extraintestinal infections such as neonatal meningitis, bacteremia, kidney inflammation, cystitis, prostatitis, and sepsis

Those at risk for E. coli-associated sepsis include neonates who are infected by their mother’s bacteria before or during birth, the very young and very old and immunocompromised people.

Sepsis and meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is an infection of the brain lining and the spinal cord, most often caused by Neisseria meningitidis or meningococcus. Meningococcal septicemia develops when the bacteria in the blood multiply uncontrollably. It is characterized by fever, stiff neck, and headache, with vomiting, photophobia and confusion in many cases. These may not be present in the very young. Meningococcal sepsis is marked by systemic symptoms like chills, myalgia, and a characteristic purple rash in more advanced stages.

Sepsis and cancer

Cancer and its treatment can disrupt patients’ immunity to infection and increase the risk of sepsis. Patients can reduce their risk by taking standard precautions to prevent infection including good hand hygiene, washing fruit and vegetables, cooking meat and eggs thoroughly, vaccination, avoiding infected people and crowded places.

Sources

- Conceição, R A et al. Human sepsis-associated Escherichia coli (SEPEC) is able to adhere to and invade kidney epithelial cells in culture. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500057.

- Nhs.uk. Sepsis. nhs.uk/conditions.

- MedinePlus.gov. Sepsis. medlineplus.gov.

- Mayoclinic.org. Sepsis. mayoclinic.org.

- Cdc.gov. Life after sepsis fact sheet. cdc.gov/sepsis.

- Stearns-Kurosawa, D. J., et al., (2011). The Pathogenesis of Sepsis. Annual Review of Pathology. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130327

- Martin-Loeches I., et al., (2015). Management of severe sepsis: advances, challenges, and current status. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S78757.

- Nasa P. et al., (2012). Severe sepsis and septic shock in the elderly: An overview. World Journal of Critical Care Medicine. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v1.i1.23.

- Bewick T. (2008). Pneumonia in the context of severe sepsis: a significant diagnostic problem. European Respiratory Journal. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104808.

- Mayoclinic.org. E. coli. mayoclinic.org.

- Sepsis.org. Sepsis and Pneumonia. sepsis.org/sepsis-and/pneumonia/.

- Cdc.gov. Meningococcal disease. cdc.gov/meningococcal.

- Cdc.gov. Cancer, infection and sepsis fact sheet. cdc.gov/sepsis.

- Health.nsw.gov. Maternal sepsis (puerperal fever) fact sheet. health.nsw.gov.au.

- Mathias B., et al., (2016). Pediatric Sepsis. Current Opinions in Pediatrics. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000337.

- Bloos F., et al., (2014). Rapid diagnosis of sepsis. Virulence. doi: 10.4161/viru.27393.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 21, 2023