Aging is defined as the gradual deterioration of the body’s physiological functions that are important for survival. Accumulation of cellular damaged products over time is the leading cause of aging. Skin, being the outermost protective covering of the body, is often subjected to both internal and external causative factors of aging.

The characteristic features of aging skin include wrinkles, dryness of the skin, reduced skin thickness, loss of elasticity, dermal and epidermal atrophy, reduced rate of epidermal cell proliferation and cellular senescence. External factors that mainly contribute to skin aging include sunlight, UV radiation, chemicals, pollutants, and smoking.

Besides external stimuli, endogenous processes that trigger the aging process include excessive free radical production, nuclear/mitochondrial gene mutation, cellular senescence, shortening of telomere, reduced cell proliferation, and impaired immune functioning. In recent years, many scientific studies have revealed that advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are also among the crucial contributory factors of skin aging.

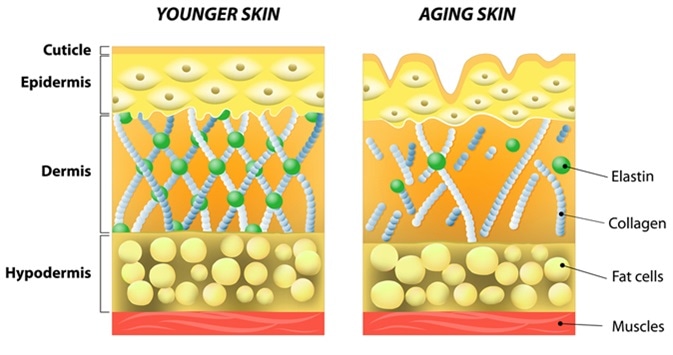

Younger skin and aging skin diagram. Image Credit: Designua/Shutterstock

Advanced glycation end products

The formation of AGEs is a very complex process that involves a spontaneous non-enzymatic reaction called glycation. Glycation is the reaction between reducing sugar and proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, wherein reactive carbonyl groups of a reducing sugar react with free amino groups of proteins to form an unstable Schiff base.

Additional rearrangement of the Schiff base results in the formation of more stable Amadori products, which are basically ketoamines or fructosamines. These reversible reaction products subsequently undergo irreversible oxidation, polymerization, dehydration, and cross-linking reactions to generate AGEs.

The progressive accumulation of these AGEs in the body is a hallmark of the aging process in humans, animals, and other organisms. Most commonly found AGEs in the skin include carboxymethyl-lysine, carboxyethyl-lysine, pentosidine, methylglyoxal and glyoxal, glucosepane and fructose-lysine. Receptors for AGEs are generally expressed in the epidermis and dermis, and it has been observed that the expression is higher in the sun-exposed areas of the skin as compared to sun-protected areas.

AGEs and skin aging

Accumulation of AGEs in the skin has been observed both in diabetes and during chronological aging. Proteins with a slow turnover rate, such as collagen I and IV, as well as long-lived proteins, such as fibronectin, are primary targets of glycation reaction in the skin. Moreover, excessive deposition of AGEs in sun-exposed skin areas suggests that solar radiation, especially UV radiation, may play an important role in the formation of AGEs.

Apart from sunlight, other external factors that are responsible for increased formation and deposition of AGEs in the skin include smoking and diet. The amount of AGEs in the food mainly depends on the method of preparation. For example, fried foods contain a higher amount of AGEs as compared to boiled foods. About 10-30% of ingested AGEs are absorbed in the body and may participate in skin aging.

Mechanistically, AGEs can react with proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids and alter their normal physiological functioning. Upon binding to their receptors, AGEs can also trigger a cascade of signaling pathways, leading to reduced cell proliferation, increase cellular senescence and apoptosis, decreased extracellular matrix synthesis, increased formation of free radicals and pro-inflammatory mediators, etc. All these processes can potentially contribute to skin aging.

Strategies to control AGEs

Since autofluorescence is an intrinsic property of AGEs, measurement of skin fluorescence is an effective method of detecting AGE deposition in the skin. Studies have found that skin fluorescence positively correlates with many age-related disorders, such as cardiovascular diseases, renal disorder, macular degeneration, and overall mortality.

Given the immense involvement of AGEs in age-related disorders, including skin aging, effective strategies/interventions are needed to prevent, or at least control, their accumulation in the body. In this regard, most efficient strategies include the removal of already formed AGEs from the body by degrading glycated proteins; inhibiting the formation of AGEs; and antagonizing the AGE-mediated signaling cascade.

Inhibition of AGE formation – aminoguanidine, a nucleophilic hydrazine, is known to prevent AGE formation by sequestering early glycation products, such as carbonyl intermediates. However, it has many adverse side effects and has no effect on advanced glycation products. Another such compound is pyridoxamine, which has shown good results in phase II clinical trials involving patients with diabetic neuropathy. This compound is known to inhibit advanced glycation products.

Do you know what AGEs are? | David Turner | TEDxCharleston

Degradation of glycated proteins

Chemical compounds, such as ALT-711, N-phenacylthiazolium, and N-phenacyl-4, 5-dimethylthiazolium, have shown to break abnormal protein cross-linking induced by AGEs. Of these compounds, ALT-711 has shown promising results in increasing skin hydration in aged rats.

Antagonizing AGE-mediated signaling cascade

Approaches that are utilized to inhibit AGE-driven signaling pathways include siRNA-mediated knockdown or small molecule inhibitor-mediated blocking of AGE receptors.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 18, 2021