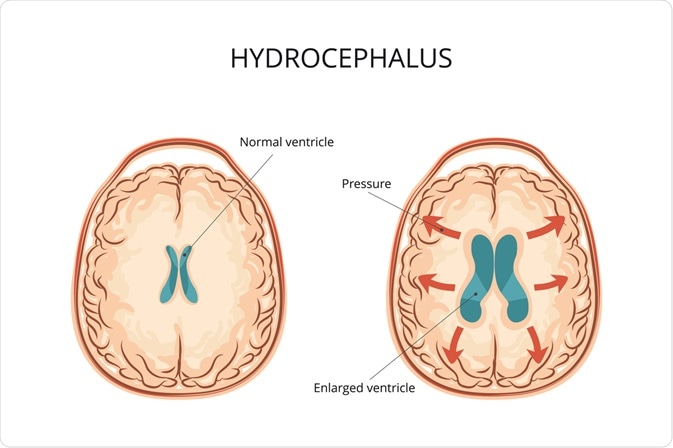

Also known as water in the brain, hydrocephalus in the pediatric population occurs due to the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the brain.

Hydrocephalus is an extremely dangerous condition that arises due to a hydrodynamic disturbance in the flow, formation, and/or absorption of CSF. Most cases are fatal if left untreated.

Hydrocephalus in the general population has a bimodal peak in terms of incidence. The first is seen in infancy and tends to be related to congenital malformations. The second peak occurs in adulthood after the sixth decade of life.

Image Credit: logika600 / Shutterstock.com

Pathophysiology

CSF is fairly similar to the liquid component of blood. It contains a variety of nutrients and salts, such as glucose and sodium. CSF is produced every minute of our lives by the choroid plexus found within the ventricular system of our central nervous system (CNS). The ventricular system is basically a system of connected chambers within the brain.

Once produced by the choroid plexus, CSF flows sequentially through the lateral ventricle, interventricular foramen of Monro, third ventricle, Sylvius cerebral aqueduct, fourth ventricle, Luschka lateral foramina, Magendie medial foramen, subarachnoid space, and the arachnoid granulation, followed by the dural sinus before finally being reabsorbed into venous drainage.

The cycle of production, flow, and absorption of CSF is rather orderly and ensures a protective environment within the CNS in addition to maintaining the balance of the nutrients and salts it contains therein. Any disruption to any component of the cycle may have deleterious consequences.

While most often hydrocephalus is due to a congenital defect, there is no known single cause that has been implicated. Some studies suggest a single chromosomal defect, while others link it to other congenital disorders like spina bifida. In addition to being born with congenital defects that can cause hydrocephalus, anatomically normal children can also develop hydrocephalus due to a plethora of complications. These complications include traumatic head injuries, tumors of the CNS, meningitis, premature birth, and intraventricular or subarachnoid hemorrhaging.

2-Minute Neuroscience: Hydrocephalus

Symptoms

The signs of hydrocephalus, as well as the symptoms, may vary depending on the age of onset. In infants, the changes that may be noted are an unusually large head that rapidly increases in size with a bulging fontanel, also known as a soft spot, at the top of the head. These infants may experience physical symptoms such as vomiting, poor feeding, sleepiness, seizures, ‘sun-setting of the eyes’ (i.e., downward fixation of the eyes), and significant deficits in muscle strength and tone, as well as growth.

Toddlers and older children may present with an abnormally larger head and similar physical symptoms that are often seen in infants, as well as unstable balance, poor coordination, and great difficulty staying awake or being aroused from sleeping. They may also exhibit cognitive and behavioral changes with a decline in academic performance, irritability, and personality changes.

Diagnosis and treatment

A rapidly enlarging head during infancy is easily detected by a pediatrician or family physician, while other signs and symptoms in older children may suggest hydrocephalus. Suspicions may be confirmed with the help of radiographic techniques.

Between 6 to 12 of age, the diagnosis of hydrocephalus may be done using ultrasound. Once the child’s skull fuses, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans are the techniques used, with the former being favored overall by most neurosurgeons. This is because it provides a better radiographic picture of the brain; however, an MRI takes longer than a CT and requires sedation in most cases.

Surgery is typically the only treatment option for hydrocephalus once a diagnosis has been made. The type of surgery that will be performed depends on the cause of the disruption to the CSF hydrodynamics. If there is a mass causing obstruction to the flow of CSF and it can be surgically removed, then this is done.

Immovable blockages require the creation of a bypass shunt to channel fluid from the ventricles to other parts of the body, such as the chest or abdominal cavity, with the latter being preferred because the CSF is easily absorbed back into the bloodstream via the bowels. In addition to shunt placement, choroid plexus cauterization combined with third ventriculostomy can also be done to reduce the production of CSF.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Mar 11, 2023