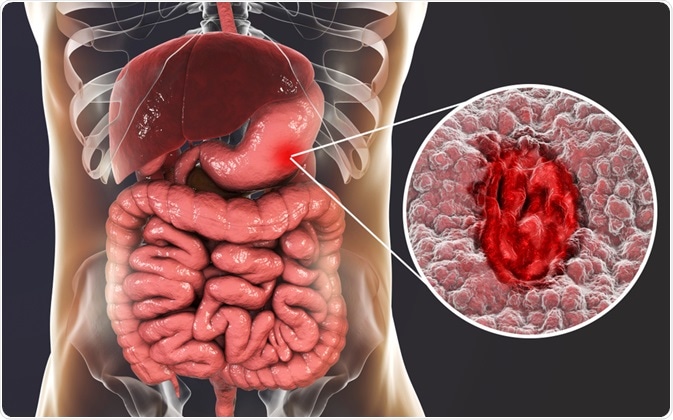

Peptic ulcers are sores within the inner lining of the stomach, duodenum section of the small intestine, and sometimes the esophagus.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

Early speculation on peptic ulcers

Although peptic ulcers are now known to be caused by either infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria or by long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), this was not always the case.

Up until the discovery of H. pylori in 1982, clinicians attributed peptic ulcers to lifestyle choices. This could have included consuming a diet rich in spicy foods and an inability to properly manage emotional and personal stress. A paper published in 1967 even reported that peptic ulcers appeared in families with dominant and obsessional mothers.

Clinicians thought that these lifestyle factors resulted in an overproduction of gastric acid, leading to the formation of ulcers. Because of this, treatment for peptic ulcers at that time was limited to adopting a bland diet, bed rest, and taking medications that blocked new acid production and neutralized existing acid. Sadly, although these agents alleviated symptoms, the ulcers had a high rate of return.

Discovery of Helicobacter pylori

The road to the discovery of the Helicobacter pylori bacteria as the infectious agent in gastritis and peptic ulcers was a long one. In the late 19th century, the Polish clinical researcher Professor W. Jaworski and the Italian medical researcher Giulio Bizzozero both observed spiral-shape micro-organisms in the gastric mucosa of humans and dogs, respectively.

However, these observances were thought to be attributed to post-mortem contamination of the tissue samples. It was the belief at the time that microorganisms could not survive the extremely acidic environment in the stomach of a living human or another mammal.

In 1982, two physicians from Perth, Australia, Dr. Robin Warren, and Dr. Barry Marshall, again observed bacteria associated with ulcerated and inflamed regions of the human gut and began investigating its role in disease. These scientists isolated the bacteria from stomach biopsies and named the organism Helicobacter pylori.

After a long trial and error period, Warren and Marshall figured out how to grow H. pylori in culture, which occurred by chance after inadvertently leaving the culture to grow over a long Easter holiday. H. pylori is slow-growing as compared with other bacteria and requires additional days of growing time. Using themselves as test subjects, Marshall and another volunteer ingested a culture of H. pylori and soon developed gastritis, thus definitively establishing a link between the infectious agent and disease. Warren and Marshall published their work in 1982 and were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005 for their outstanding contributions to the field.

Modern discoveries

Warren and Marshall’s discovery opened the floodgates for H. pylori research. It was soon discovered that H. pylori infection could be quickly identified using patient blood samples by detecting anti-H. pylori antibodies made against the bacteria.

Other quick and inexpensive methods of testing soon followed. These tests are important for performing epidemiological studies for H. pylori infection rates.

Nearly two-thirds of the worldwide population is infected with H. pylori, with rates varying by geographical region and ethnicity. Developing countries have higher rates of infection as compared to developed countries, most likely due to suboptimal sanitation or inconsistent access to clean drinking water. It is estimated that H. pylori infection in developing nations is likely to occur in children by age 10.

It is important to note that not everyone who is infected will develop peptic ulcers. However, researchers have also established a link between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, which is the 14th most common cause of death worldwide. Therefore, proper eradication of H. pylori could be instrumental in preventing the development of gastric cancer later in life. Academic and industry scientists are actively pursuing a vaccine against H. pylori in order to address this worldwide health concern.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 23, 2023