Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a broad term, which is used to describe several cardiac defects that may be found at birth, and affects proper heart function to varying degrees.

Image Credit: Puwadol Jaturawutthichai/Shutterstock.com

CHD is the most prevalent inborn disorder found in new-born babies, and it is the main cause of death from congenital birth defects in the perinatal period and during infancy. It is estimated that CHD may occur in up to as many as 13 in every 1000 live births, and mortality, as well as morbidity, are largely dependent on early diagnosis and timely transfer to specialized institutions with the necessary capacity to treat these conditions.

Risk factors associated with CHD

Several factors have been implicated in the development of CHD. One such risk factor is having a positive family history. It is approximated that there is a three-fold risk for expectant mothers and/or fathers, who have first-degree relatives who may have been affected by CHD.

In addition to genetics, other maternal factors may play a role, and these include, but are not limited to conditions such as viral infections during pregnancy, as well as obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, epilepsy, and a range of connective tissue disorders.

A mother may also put her unborn child at risk by consuming alcohol and/or smoking during pregnancy. Likewise, some medications have also been linked to cardiac defects in new-born babies. There has also been a noted increase in CHD among infants who are born preterm as opposed to those who are born at term.

Individuals who are born with certain genetic conditions, for example, Down syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, and neurofibromatosis are also at an increased risk of having some cardiac defects.

Signs and symptoms

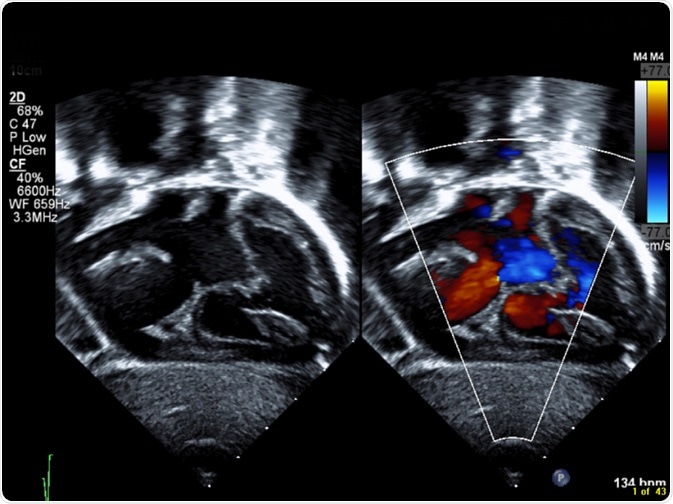

CHD may present with an array of signs and symptoms, some of which may be apparent immediately after birth, and others may not be until later in childhood or even early adulthood. Among these signs and symptoms is a cyanotic appearance, which is a bluish tinge to the skin, due to inadequate oxygen flow throughout the tissues.

Additionally, the infant may have an extraordinary fast heartbeat with a corresponding fast rate of breathing. There may be noticeable swelling around the eyes, abdomen, or legs. These children generally thrive very poorly in comparison to their peers. In older children and young adults, there may a constant complaint of fatigue, unusual tiredness, and respiratory difficulties.

Types of CHDs

Although there are many different CHDs, they may be grouped into CHDs that cause septal defects, narrowing of the aorta, narrowing of the pulmonary valve, transposition of the main vessels of the heart, and underdevelopment of the heart.

Septal defects are colloquially known as “holes” in the heart. These arise when there are abnormal connections between any of the heart’s chambers, which normally only communicate via a system of valves that open and close with contraction of the heart.

Narrowing of the aorta is also better known as aortic coarctation. The significance of this CHD is that it reduces the amount of oxygen-rich blood that should be transported to the rest of the body. Signs and symptoms depend on the degree to which the aorta is narrowed, and these present much earlier in life with significant narrowing.

Similarly, there may be narrowing between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery, known as pulmonary stenosis. This makes it significantly harder for the heart to pump blood to the lungs and results in increased strain on the heart, which in turn may present with some of the abovementioned signs and symptoms.

Transposition of the great arteries, although rare, is a serious condition. There is swapping between the two main blood vessels (i.e. the pulmonary artery and the aorta) that exit the heart. When this occurs, there is no longer the physiological flow of blood from the pulmonary artery to the lungs to collect oxygen that is later sent to the rest of the body from the heart via the aorta.

Instead, blood flows to the lungs and picks up oxygen, but that oxygenated blood is pumped back into the heart ultimately as opposed to being pumped to the rest of the body.

Image Credit: Sumer McNitt/Shutterstock.com

Management of CHDs

CHDs are managed according to the type and severity of the defect. While some CHDs are simply not compatible with life, others may be mild, and even heal on their own. For example, some septal defects may close spontaneously over time, while others may require specialized surgical intervention.

Thanks to advances in medicine, science, and technology, there are novel means of achieving near-normal cardiac function for many CHDs if caught early and referred to tertiary care without delay. More complex CHDs, despite surgical intervention, may cause lifelong problems, greatly affecting an individual’s capacity to do everyday activities.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 6, 2020