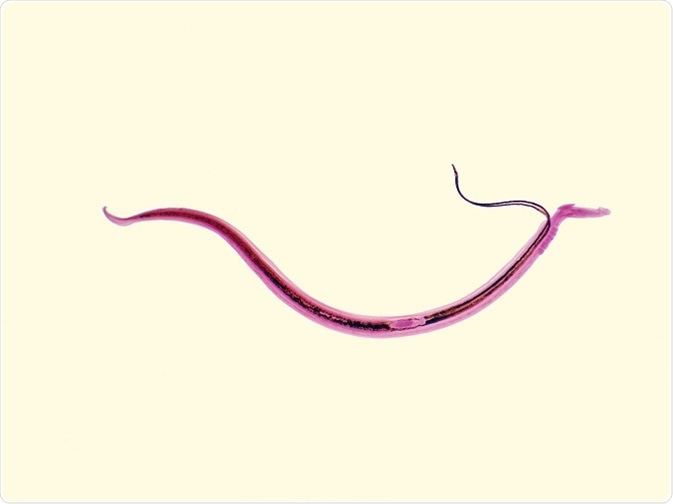

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, snail fever, or Katayama fever, is an infectious disease caused by parasitic worms of the genus Schistosoma. This condition can affect either the urinary tract or the intestinal tract, depending on the species.

Image Credit: Jubal Harshaw / Shutterstock.com

Epidemiology

Schistosomiasis is the third most prevalent parasitic disease and has the second-largest impact on humans as compared to all other tropical diseases, after malaria.

Throughout the world, more than 207 million people are affected by schistosomiasis, with a further 700 million at risk if they live in endemic regions. More than 80% of cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, although it is also a major health issue in other areas of the world, particularly Egypt and China. Poor and rural communities are the most affected by schistosomiasis, with its greatest prevalence observed among young adolescents.

The mortality rate of the condition is 14,000 deaths per 200 million cases per year. This is relatively low, considering the number of potentially severe complications associated with schistosomiasis.

Dr. Claude Oeuvray (Merck): Female Genital Schistosomiasis

Causative Species

There are several different species of Schistosoma that may cause the infection, including:

- S. haematobium: The only genus to cause urinary schistosomiasis and is the most widespread species, particularly found in Africa and the Middle East.

- S. intercalatum: This species is found in rainforest areas of central Africa.

- S. mansoni: This species is found in more than 52 countries worldwide and is only species to affect Latin America.

- S. japonicum: This species is found in China, Indonesia, and the Philipines

- S. mekongi: This species is found in Cambodia and Laos.

Pathophysiology

Infection with parasitic worms of the genus Schistosoma is responsible for causing schistosomiasis.

Transmission of the parasites occurs when the skin of humans comes into contact with freshwater that is infested with larvae that penetrate the skin. The larvae develop into adult schistosomes in the body and eventually reside in the blood vessels.

The female worms lay eggs, which are excreted from the body through the feces or urine. Some of the eggs are not excreted from the body easily and become trapped in the gastrointestinal or urinary tissues. This can cause significant immune reactions and eventual damage to the organs involved. The eggs can then hatch in freshwater, with the aid of fresh-water snails, to continue the life cycle of the parasitic infection.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients may experience symptoms as a result of a reaction to the worms’ eggs.

Intestinal schistosomiasis is associated with symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stools. If the infection continues on a chronic basis, it is common for the liver to become enlarged and an accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity may occur.

Urogenital schistosmiasis is characterized by hematuria. In chronic infections, damage to the urinary system can occur, such as fibrosis of the bladder and ureter, as well as kidney damage that may lead to kidney failure. Infertility and other sexual problems present in some cases and a rare complication is bladder cancer.

Children with schistosomiasis may exhibit signs of delayed growth and learning difficulties as a result of the condition.

Prevention

Unclean water sources play an essential role in the life cycle of the parasitic worms and must be addressed to improve methods of prevention. At-risk areas must be identified to improve the sanitation standards, control the snails that continue the life cycle of the parasites, as well as provide educational information about hygiene.

Medications such as praziquantel are used to treat people with the infection at regular periods to prevent the continuation of the infection. Children and adults in endemic areas should be treated to help prevent infection outbreaks. The treatment is often repeated annually for several successive years in high-risk areas.

References

Further Reading

Further reading:

Last Updated: Apr 30, 2021