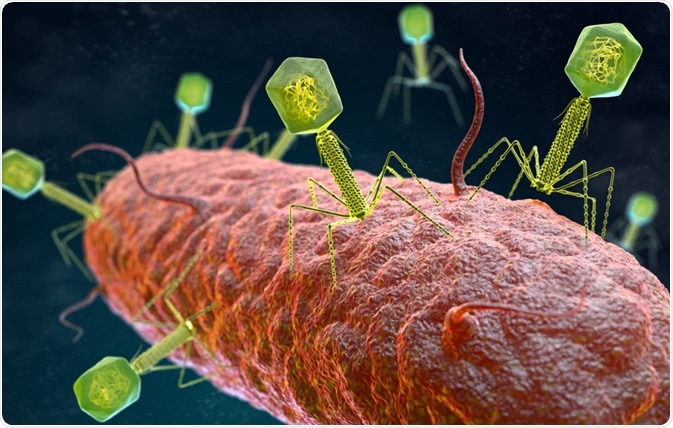

Transduction is the biological process by which DNA is transferred into a cell with the aid of a viral vector. This may take place naturally between bacterium via a bacteriophage in an example of horizontal gene transfer, or can be intentionally exploited in the laboratory to modify the mammalian cell genome using a viral vector.

Image Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

There are two forms of transduction: generalized and specialized. During generalized transduction, random sections of bacterial DNA are packaged into a phage and transferred into another bacterium, wherein the DNA is either recycled or exchanged for a homologous region in the new host’s genome.

If the inserted DNA is in the form of a plasmid then it is generally re-formed within the host cell to remain a plasmid, though may transiently be inserted into the host genome. Generalized transduction usually occurs when phage particles mistakenly incorporate bacterial DNA into a phage head instead of the intended phage DNA following lysis.

Phages insert their genetic material, the prophage, into a host cell where it is incorporated into the bacterial DNA chromosome for transcription. In specialized transduction, only a limited set of bacterial genes can be transferred to another bacterium, those that flank the prophage following incorporation and upon excision from the bacterial genome.

The prophage, along with the imprecisely excised bacterial DNA, together known as a heterogenote, is re-packaged into a phage upon excision, where it is delivered to a new host cell. Following injection into a new host, the heterogenote may replace homologous host bacterial DNA, thereby incorporating additional bacterial DNA from the first host.

Transduction is distinct from transformation or conjugation, wherein exogenous DNA is incorporated into a bacterium by passing the cell membrane from the surrounding medium or another bacterium in direct contact, respectively.

The DNA involved in transformation is sensitive to DNase, which is usually present outside of the cell and thus is likely to encounter the DNA during transfer. In conjugation, the DNA is not exposed to the external environment, while in transduction the DNA is protected by the phage particle, and thus neither is sensitive to DNase.

The origins of transduction

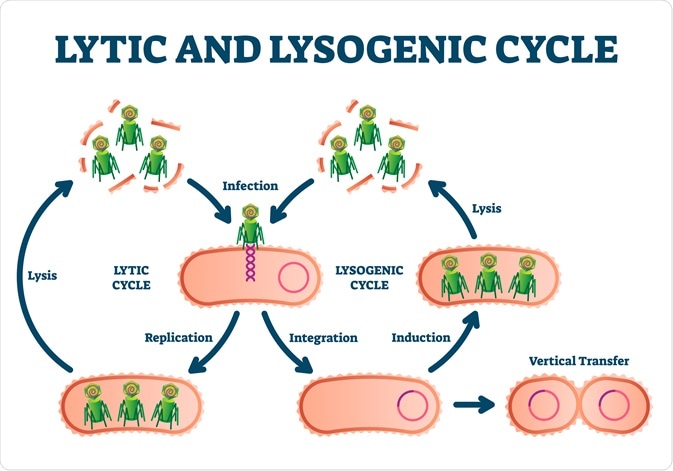

In lysogenic bacterium, those able to produce and transfer the ability to produce a phage, the prophage helps to protect the cell from additional infection. In a small percentage of lysogenic cells the prophage will become activated, producing phages and causing the cell to lyse, releasing the phage into the environment and infecting nearby non-lysogenic cells.

Virulent phages are always lytic, meaning that they ultimately result in cell membrane rupture. Temperate phages can exist within bacteria and confer resistance to infection, though may sometimes cause bacterial lysis.

A lysogenic E. coli strain was among the first identified, bearing a temperate phage known as lambda phage (phage λ). Conjugation in E. coli is driven by a plasmid called the fertility factor (F), which is found in only some E. coli cells in a culture. F+ cells conjugate with F- cells preferentially, wherein the F- cell is converted into an F+ cell by plasmid transfer. Crossing F+ with F-(λ) cells results in recombinant lysogenic recipients, while crossing F+(λ) with F- cells does not.

This suggested to early researchers that phage λ was acting as though it was part of the bacterial chromosome, as opposed to existing as a plasmid in the bacteria and passing over during conjugation.

Later, it was noted that phage λ always enters F- cells when the lytic cycle is induced, and is inserted between the gal and bio regions of the host chromosome. When properly excised the prophage forms a plasmid, though occasionally frame shifted excision can result in only part of the prophage sequence being removed in association with a section of either the gal or bio regions, leaving some of the prophage genes behind.

Image Credit: VectorMine/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: VectorMine/Shutterstock.com

The prophage is then packaged into a phage head and injected into another cell. As the prophage is inserted into a specific point in the new host's genome, between the gal and bio regions, gal or bio genes from the original cell are transduced into the new host in this way.

As this may result in the new host cell bearing two alleles for the same gal or bio region gene, specialized transduction can result in partial diploid cells, and less commonly in transduced haploid cells where the host allele has been replaced by the incoming one.

Some transducing phages lack the usual end group that allows them to circularize and form a plasmid, meaning that transduction does not occur by insertion of the prophage into the host genome but rather by homologous recombination of the original host’s gal or bio genes, and therefore these cells are not partially diploid.

Transducing phages have been utilized in a number of research applications surrounding gene delivery and sequencing. A set of λ transducing phages have been developed that allow researchers to quickly map the genome of novel E. coli strains, and the role of various genes have been uncovered by adjusting the relative number of regulatory elements in the genome using imprecisely excised prophages.

Phages are used in a number of other applications from vaccines to food preservation, and the capacity to transfer genes by transduction plays a role in many of these functions.

Sources

- Griffiths, A. J. F., Miller, J. H., Suzuki, D. T., et al. (2000) An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. 7th edition. New York: W. H. Freeman. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Griffiths, A. J. F., Gelbart, W. M., Miller, J. H., et al. (1999) Modern Genetic Analysis. New York: W. H. Freeman. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Weisberg, R. A. (1996) Specialized Transduction. ASMScience. https://asm.org/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 19, 2023