A virus is the smallest type of parasite to exist and is typically within the size range of 0.02 to 0.3 micrometers (μm) in size; however, some viruses can be as large as 1 μm.

Image Credit: Rolling Stones / Shutterstock.com

The contents of a virus

Viruses consist of short sequences of nucleic acid, which can be ribonucleic acid (RNA) or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) as their genetic material. Unlike most other organisms, where DNA is always a double-stranded structure, viruses are unique because their DNA or RNA material can be either single-stranded or double-stranded.

The typical structure of a virion, which is the term used to describe a single virus, includes an outer shell that is otherwise referred to as the protein capsid or membrane. The primary function of this outer shell is to protect the virion’s genetic information from physical, chemical, or enzymatic damage.

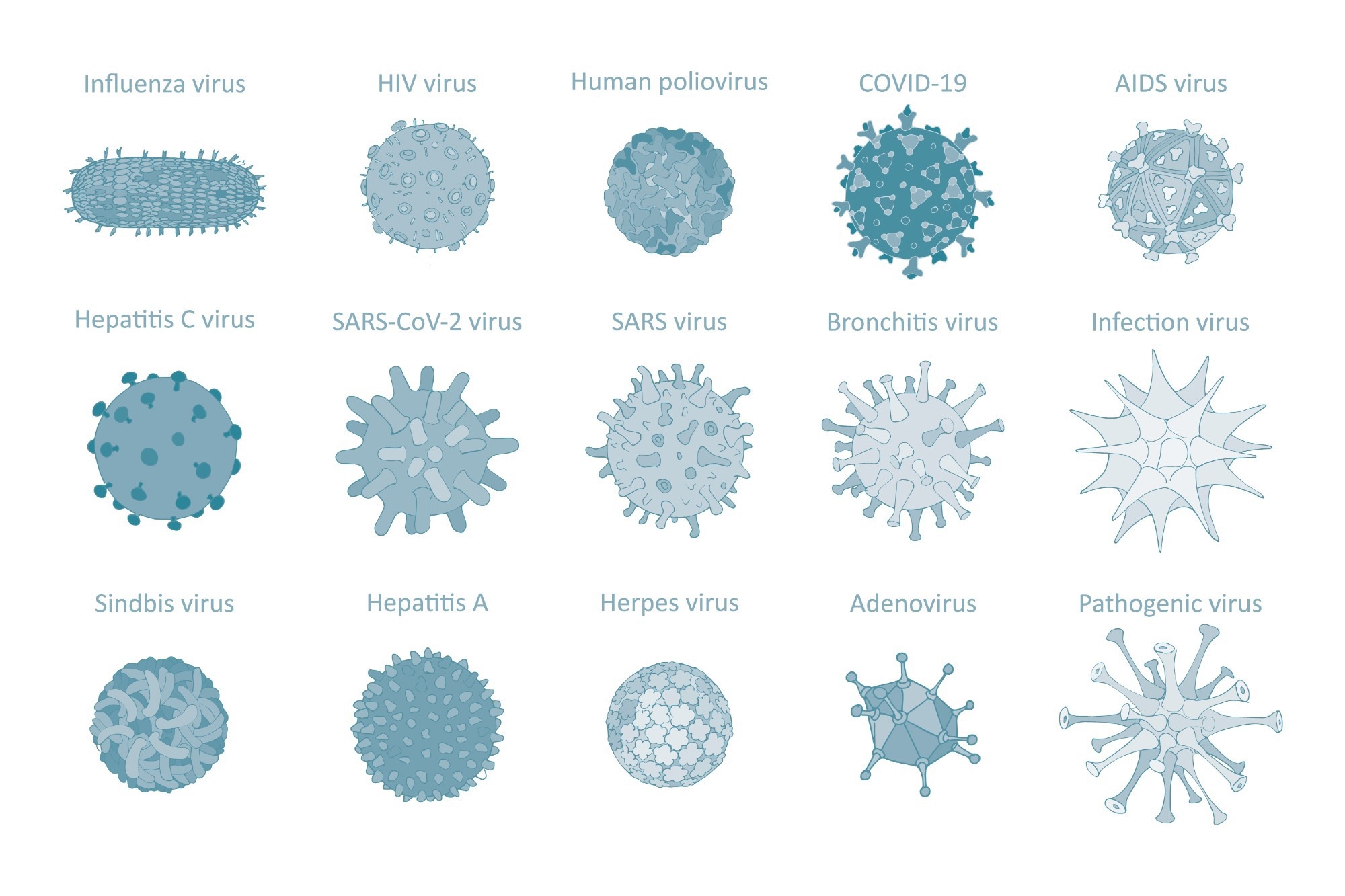

Classifying human viruses

A virus is often classified according to its physicochemical properties, genome structure, size, morphology, and molecular processes. In terms of their genetic material, viruses are classified according to whether they are RNA or DNA viruses and the strandedness of their genetic material, which can include double-stranded (ds), single-stranded (ss), or partially ds. Furthermore, ss viruses will also be classified as to whether they are positive ss, negative ss, or negative with ambisense viruses.

To date, five dsDNA human virus families have been identified, which include adenoviridae, herpesviridae, papillomaviridae, parvoviridae, and poxiviridae. Picobirnaviridae, picornaviridae, and reoviridae are the three human dsRNA viruses that have been identified.

As compared to DNA viruses, there have been many more RNA viruses that have infected humans. These include nine negative ssRNA and eight positive ssRNA virus families.

Capsid morphology, including icosahedral, helical, or complex shapes, can also be used to classify a given virus. The presence or absence of an envelope on the virus is also incorporated into its classification.

Image Credit: Cartoon Millie_art / Shutterstock.com

How do viruses infect?

The outer surface of the virus is crucial for its ability to recognize and attach to host cells. Typically, the surface of the virus will contain certain proteins that can recognize and bind to cellular receptors to facilitate its attachment to the host cell. Once the virus attaches to the host cell, it is engulfed through the cellular membrane and subsequently enters the cell’s cytoplasm. Inside the cell, the virus will remove its viral coat into smaller cellular vesicles, thereby releasing its genetic material into the cytoplasm for its replication.

Viruses do not have the mechanisms needed to survive independently and seek out plant, animal, or bacterial host cells where they can replicate using those cells' machinery. Therefore, viruses will use one of several different transmission routes to infect host cells, which include direct contact, indirect, common vehicle, and airborne transmission.

Viruses do not have the mechanisms needed to survive independently and seek out plant, animal, or bacterial host cells where they can replicate using those cells' machinery. Therefore, viruses will use one of several different transmission routes to infect host cells, including direct contact, indirect, common vehicle, and airborne transmission.

Direct contact transmission

The direct contact transmission route requires physical contact between an infected and uninfected subject through kissing, biting, or sexual intercourse, for example. Some of the most notable sexually transmitted viruses include the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 (HPV-16 and HPV18, respectively).

Indirect transmission

The virus is transmitted indirectly through contact with contaminated objects or materials, such as medical equipment or shared eating utensils.

Common vehicle transmission

Common vehicle transmission refers to when individuals are exposed to the virus from a contaminated source such as food, water, medications, or intravenous fluids. Whereas cytomegalovirus is a urine-associated virus, several viruses are transmitted through the fecal-oral route, including polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, hepatitis A virus, rotavirus, astrovirus, and norovirus.

Airborne transmission

Airborne transmission refers to the respiratory route of exposure to viruses that can be in the form of droplets, aerosols, and respiratory secretions on the hands and objects. Some of the most notable viruses that are transmitted through this route include influenza virus, varicella-zoster virus, human rhinovirus, human adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumovirus, and coronaviruses.

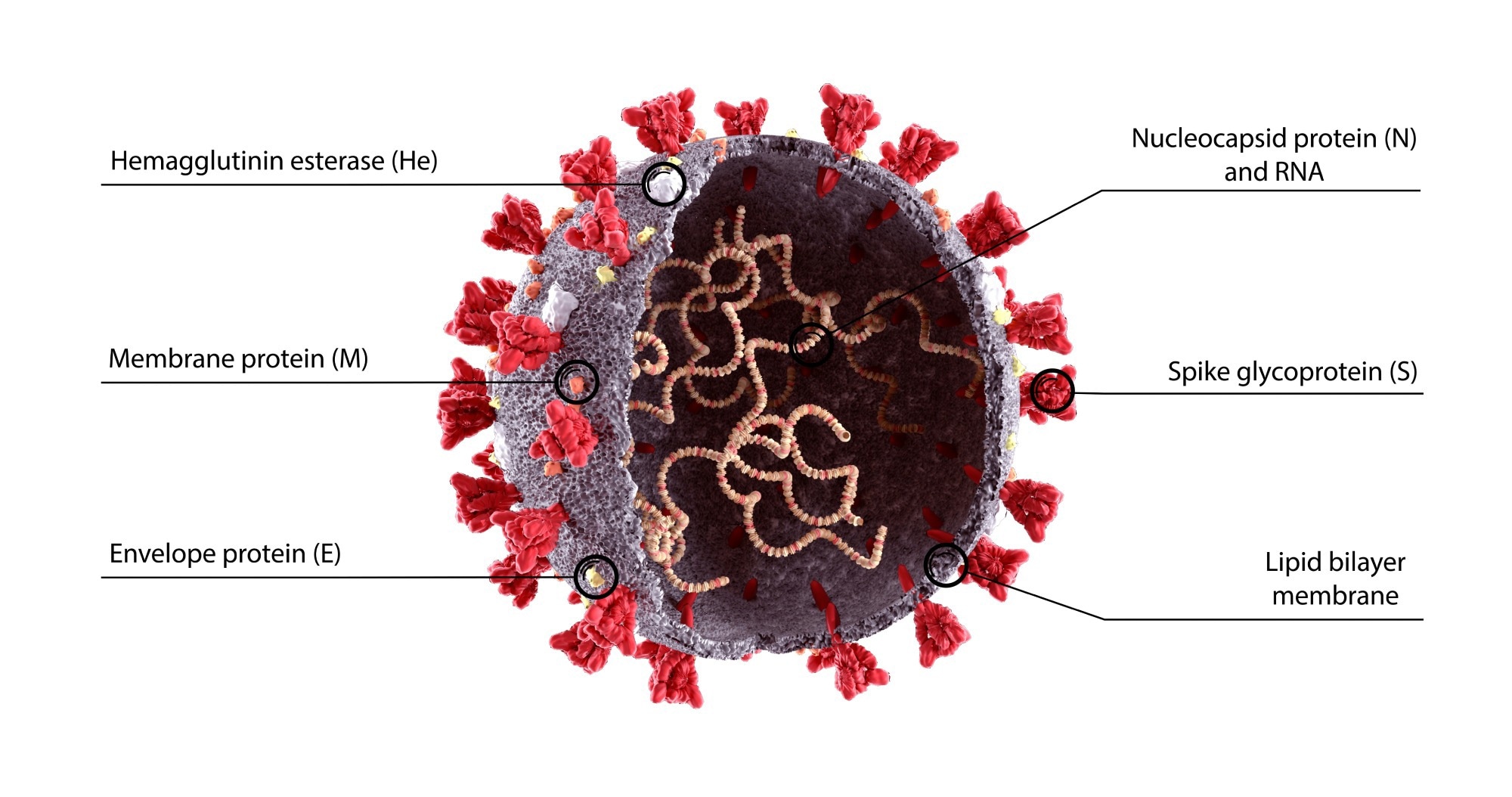

Coronaviruses

Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock.com

Within the coronaviridae family are several coronaviruses that can cause both respiratory and digestive diseases in vertebrates. The most recent coronavirus to alter both society and human health around the world is the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The term coronavirus is based on the crown-shaped spike proteins that wrap around the surface of these viruses. Within these spike proteins is the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which plays a crucial role in coronaviruses' entry into host cells. For example, both the RBDs of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 bind to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor present on the surface of host cells to gain entry.

Coronaviruses, which are enveloped, positive-sense ssRNA viruses, can be further categorized into four genera, including alpha-beta-, delta-, and gammacoronaviruses. Whereas bats are often the reservoir for a majority of alpha- and betacoronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, wild birds are more likely to be reservoirs for gamma- and deltacoronaviruses.

Coronaviruses can be further split into distinct species due to their rapid evolution capabilities. To this end, they exhibit high mutation rates and homologous RNA recombination, both of which contribute to their extensive diversity and the recurrent emergence of new variants.

Certain alphacoronaviruses like NL63 and 229E, as well as betacoronaviruses like OC43 and HKU1, cause mild symptoms in humans that are associated with the common cold. Comparatively, SARS-CoV-2 infection has the potential to cause extremely severe symptoms that lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. In fact, as of June 26, 2024, SARS-CoV-2 has infected over 775 million people around the world and caused over 7 million deaths.

Continuous Adaptive Evolution in Endemic Human Viruses

Recent research highlights ongoing adaptive evolution in several endemic human viruses, particularly in their surface proteins, which play a critical role in immune evasion. This adaptive evolution is driven by the need for viruses to evade the host's immune system, especially neutralizing antibodies that are produced following infection or vaccination.

SARS-CoV-2 has been noted to accumulate protein-coding changes at a faster rate compared to other endemic viruses, underscoring its rapid adaptive evolution. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein, which undergoes frequent mutations to escape immune detection.

The study of 28 human endemic viruses found that 10 of these viruses are undergoing significant antigenic evolution. This demonstrates that immune evasion is a common strategy among viruses that persist in human populations. This insight is crucial for informing vaccine development and predicting future viral evolution.

The research also emphasized the importance of monitoring viral evolution to manage and mitigate the impact of viral diseases effectively. Understanding the mechanisms behind antigenic evolution can aid in the design of more effective vaccines and therapeutic strategies, ensuring better preparedness for both existing and emerging viral threats.

Sources

- Taylor, M. W. (2014). What Is a Virus? Viruses and Man: A history of Interactions; 23-40. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00758-1_2, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7122971/

- Woolhouse, M., Scott, F., Hudson, Z., et al. (2012). Human viruses: discovery and emergence. Philosophical Transactions B 367(1604); 2864-2871. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0354, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2011.0354

- Siegel, R. D. (2018). Classification of Human Viruses. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases; 1044-1048. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-40181-4-00201-2, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780323401814002012

- Nova, N. (2021). Cross-Species Transmission of Coronaviruses in Humans and Domestic Mammals, What Are the Ecological Mechanisms Driving Transmission, Spillover, and Disease Emergence? Frontiers in Public Health. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.717941, www.frontiersin.org/.../full

- Kistler, K. E., & Bedford, T. (2023). An atlas of continuous adaptive evolution in endemic human viruses. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(11), 1898-1909.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.09.012, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1931312823003803

- COVID-19 cases | WHO COVID-19 dashboard. (n.d.). Datadot. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19

Last Updated: Jun 26, 2024