Introduction to Gluten

Structure of gluten

Gluten and health benefits

Gluten and autoimmunity

Wheat allergies and gluten

Gluten-free diet

References

Further reading

Introduction to Gluten

Gluten is a protein found in some food grains commonly eaten. These primarily include wheat, barley, and rye.

Gluten makes up about 85 to 90% of the protein in wheat and is a complex mixture of multiple distinct but related proteins, mainly gliadin and glutenin. These proteins, rich in glutamine and proline amino acids, are also called prolamines. Other gluten proteins can be classified based on their sulfur content, molecular weight, and primary structures of gliadins, viz., alpha, beta, gamma, and omega (α, β, γ, and ω) gliadins. All gluten proteins are bound by covalent and non-covalent forces, which also contribute to the unique properties of gluten.

While wheat or rye bread may be the most obvious source, gluten may also be present by cross-contamination in other foods, such as monosodium glutamate or soy sauce, ice cream and processed meat, or gluten-free grains like oats. This is because these products may be produced in a shared manufacturing facility with wheat. Its heat stability and capacity to act as a binding and extending agent enables the use of gluten as an additive in processed foods. It helps improve texture, flavor, moisture retention and increases the volume and protein content of processed foods.

Credit: Billion Photos/shutterstock.com

Credit: Billion Photos/shutterstock.com

Structure of gluten

Gluten is a unique structural protein that forms a network when kneaded and brings about the stretchy quality of baked wheat products. The ratio of glutenins to gliadins and their interactions determine the gluten properties referred to as viscoelasticity. More specifically, hydrated gliadins contribute to dough viscosity and extensibility, whereas hydrated glutenins, having cohesive properties, contribute to dough strength and elasticity.

Other proteins structurally similar to gluten, including secalin, hordein, and avenins, exist in other grains, such as rye, oats, and barley. Gluten varies between various wheat genotypes because of the possible combinations of gliadins and glutenins, depending on where the wheat is grown, how it is milled, and the genetic makeup of the grain.

Gluten and health benefits

Most people can consume gluten most of their lives without any adverse effects. Whole-grain bread is naturally enriched in several vital nutrients, including iron, calcium, fiber, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and folate. Gluten also improves general health by lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Studies have linked whole grain consumption with improved health outcomes. On the contrary, studies have shown that non-celiac individuals who avoid gluten may increase their risk of heart disease due to reduced consumption of whole grains.

Some studies also suggest that gluten is a prebiotic and encourages the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as bifidobacterial in the colon, which prevents gut inflammation, irritable bowel syndrome, and colorectal cancer.

Gluten and autoimmunity

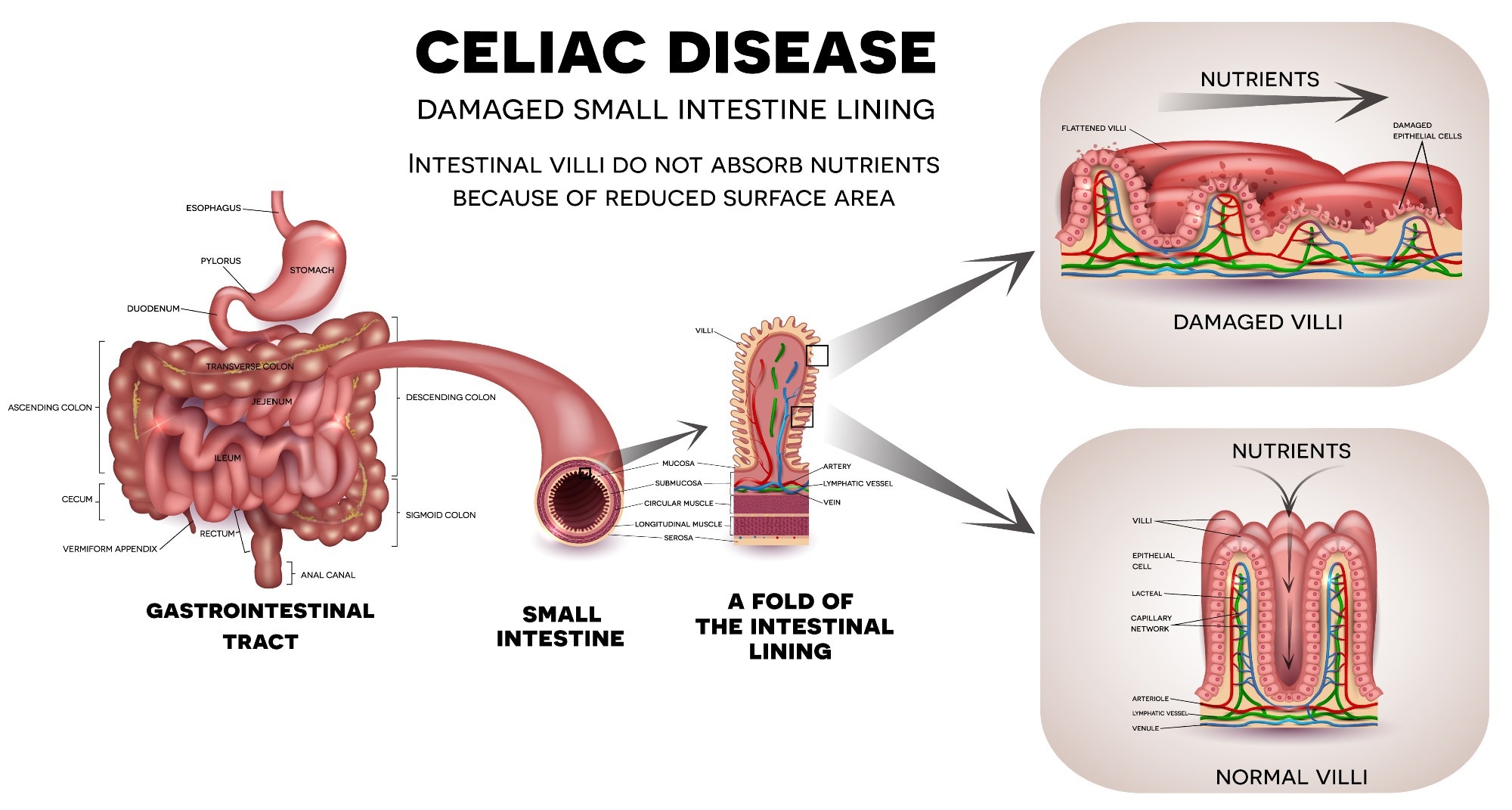

Gluten may trigger autoimmune-mediated gut inflammation called celiac disease in those with particular specific human leucocyte antigen (HLA) types - viz., DQ2 or DQ8. Some specific antigenic sequences (epitopes) of amino acids rich in proline and glutamine escape digestion in the gut and may enter the submucosal space below the gut lumen. Over there, they interact with the innate immune cells and T-lymphocytes and cause immunologic reactions.

There they interact with the innate immune cells and T-lymphocytes and cause immunologic reactions. There are hundreds of immunogenic peptides, most commonly from α-gliadin, which differ in potency, and individual patients with celiac disease may react to only a few of them.

Gluten intolerance and celiac disease affect about 1% of the population each; therefore, the majority of the population may not benefit from a gluten-free diet. Gluten may also cause another auto-immune disorder, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH), with or without celiac disease. DH is a persistent red itchy skin rash causing blisters and bumps. Furthermore, there is gluten ataxia, an auto-immune disorder that affects nerve tissues that help control voluntary muscle movement.

Wheat allergies and gluten

Wheat allergy is not the same as celiac disease, but it results from a usually temporary intolerance to one or more proteins in wheat. Immunoglobulin E (IgE) tests positive. The symptoms include swelling and itching of the lips or mouth or even the throat, breathing difficulties, nausea and cramps or diarrhea, and in severe cases, an anaphylactic reaction with vascular collapse. Roughly 0.4% of the world population is allergic to wheat, with the majority of cases in children. However, most children with this condition outgrow it with time.

Celiac disease affected small intestine.Image Credit: Tefi / Shutterstock

Celiac disease affected small intestine.Image Credit: Tefi / Shutterstock

Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity also referred to as gluten-sensitive enteropathy (GSE) or gluten intolerance, has been identified in a heterogeneous group of a small number of patients. However, further research could confirm its diagnosis, prevalence, and management.

Some studies raised concerns that people with gluten intolerance have a slightly higher risk of developing cognitive impairment. However, recent research disproved these claims and demonstrated that unless a person has celiac disease or wheat allergy, eating gluten does not negatively affect brain health.

Gluten-free diet

A gluten-free diet, which excludes gluten-containing foods from the diet, helps manage signs and symptoms of celiac disease and other gluten-related medical conditions. However, consumer surveys show that people select gluten-free foods because they think they are healthier and improve digestive health. As a result, the majority of buyers are people who do not have celiac disease. Perhaps, this is why the gluten-free food industry has witnessed a tremendous upsurge in the past few years, with a record $12 billion in sales in 2015.

There is no scientific data to show a specific benefit of following a gluten-free diet. In fact, research following patients with celiac disease who change to a gluten-free diet shows an increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome, likely due to improved intestinal absorption. However, it is also true that processed gluten-free foods have a higher glycemic index and may contain refined sugars and saturated fats. Often, these foods are made with processed rice, tapioca, corn, or potato flour. Notably, some whole grains are also inherently gluten-free, including quinoa, brown, black, or red rice, buckwheat, amaranth, millet, corn, sorghum, and gluten-free oats.

Overall, gluten is a normal part of the diet for most people and is health-promoting when ingested as part of whole grain. However, a gluten-free diet would be advisable for the small minority who are intolerant or allergic to wheat or have celiac disease.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 5, 2022