Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 / COVID-19

Ebola

Avian influenza

Conclusion

References

Further reading

Introduction

Diseases that naturally transmit between people and vertebrates are called zoonoses. These diseases are further classified as epidemic zoonoses that are sporadic, endemic zoonoses that occur in many places, and emerging and re-emerging zoonoses that appear in a new population or re-emerge rapidly in incidence or geographical range. For example, the 2009 influenza H1N1 pandemic and the recent Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

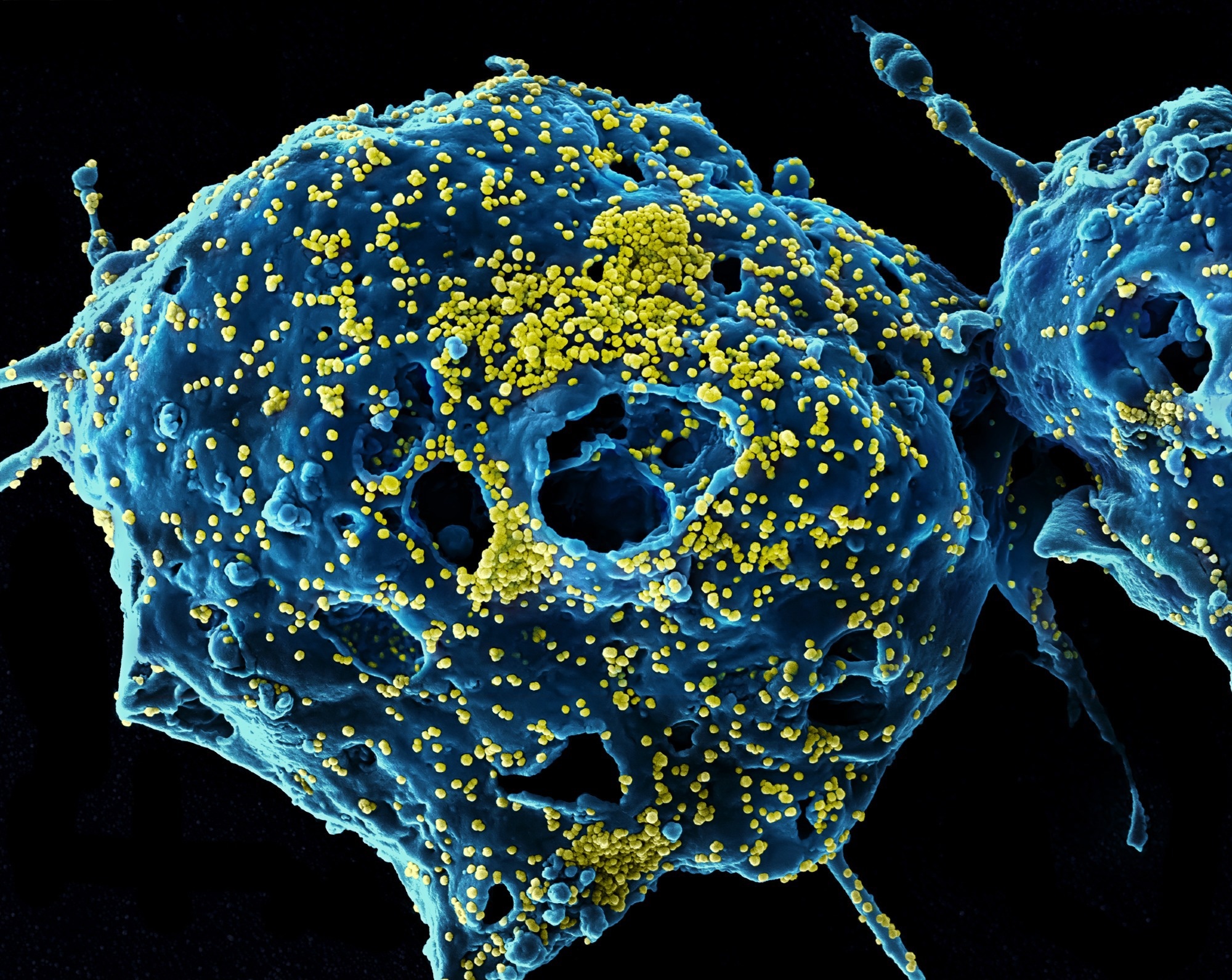

MERS Virus Particles Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus particles (yellow) attached to the surface of an infected VERO E6 cell (blue). Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Globally, nearly 60% of emerging infectious diseases reported globally are zoonoses. These diseases are a concern because of their high case fatality ratio and the absence of specific treatments and vaccines available to control their spread. New outbreaks of zoonotic diseases continue to occur as the human-animal interface grows. Destruction of animal habitats and human population sprawl increase contact between humans and animals. Studies have linked decreasing forest cover to a rise in incidences of diseases, particularly in tropical, bio-diverse areas. Also, zoonotic outbreaks due to vectors, such as the West Nile virus, pose an increasing risk to human health due to climate changes.

Zoonoses previously limited to specific geographical locations can now spread due to globalization of markets and increased worldwide travel. A recent study by Patrick R. Stephens et al. characterized the 100 most significant zoonotic disease outbreaks. They found that large outbreaks tended to have more drivers related to vector abundance, human population density, unfamiliar weather conditions, and water contamination. Moreover, pathogens causing large outbreaks were more likely to be viral and vector-borne.

Because of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the need for coordinated worldwide responses to new infectious agents in order to prevent epidemics. WHO was instrumental in limiting recent outbreaks of the Ebola virus, avian influenza virus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

SARS-CoV-2 / COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was an unrelenting demonstration of the devastating impact of zoonotic disease. Over 600 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, including more than 6.5 million deaths, have been reported to the WHO.

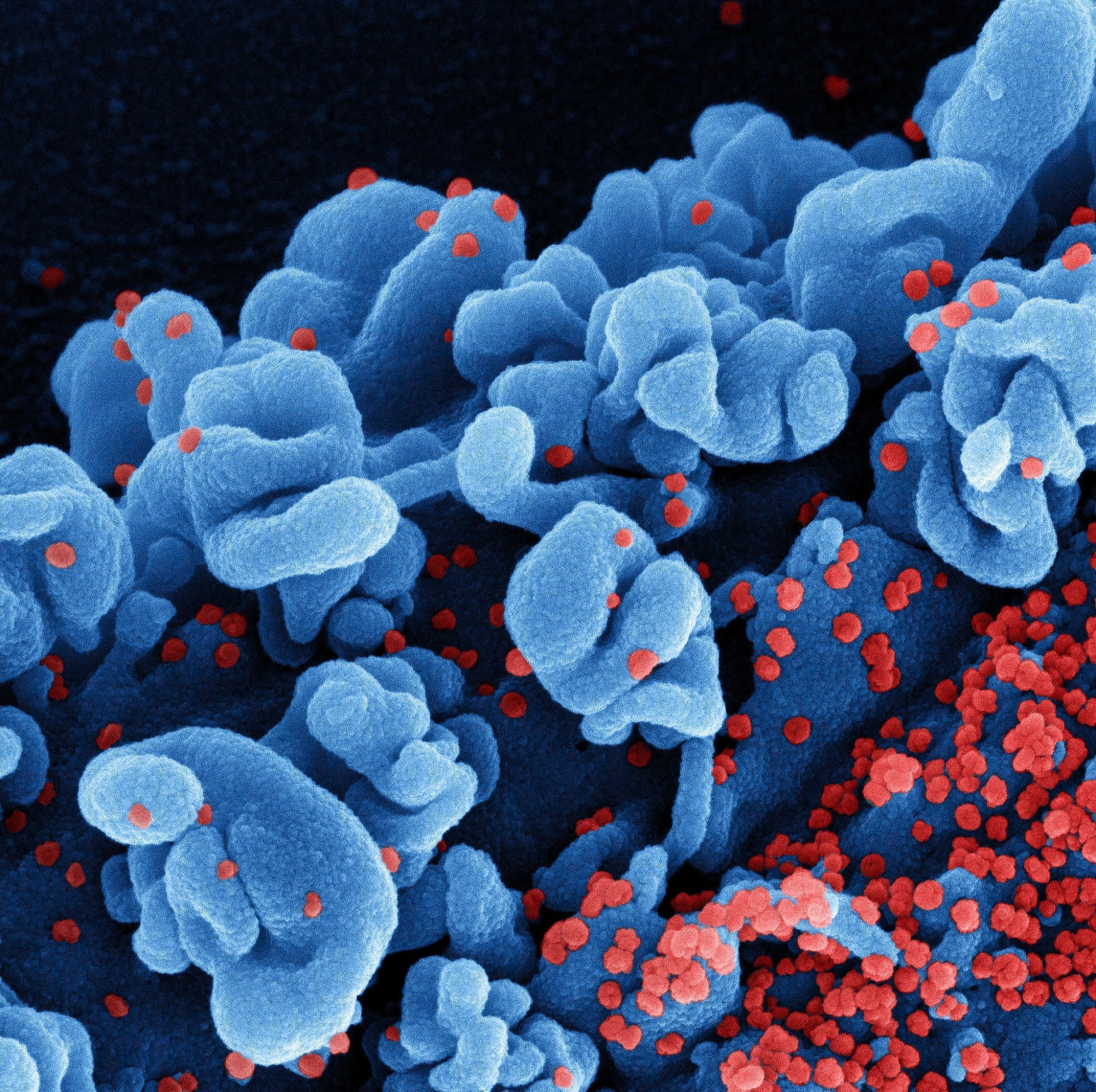

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron) Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a cell infected with the Omicron strain of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (red), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron) Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a cell infected with the Omicron strain of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (red), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

It highlighted the antiquity of zoonotic diseases and taught that viruses and humans are ubiquitous components of global ecosystems that regularly move between interacting species. For example, in the case of SARS-CoV-2, reservoir, novel, and intermediate hosts were bats, humans, and pangolins/raccoon dogs.

Despite a range of host genetic, immunological, ecological, and epidemiological barriers to successful cross-species transmission, SARS-CoV-2 infection spread to cats, dogs, lions, tigers, mink, and white-tailed deer in the US, where the virus attained high levels of prevalence in some populations.

The evolutionary lineage containing SARS-CoV-2—the sarbecoviruses—has a complex history of genomic recombination, which increases genetic diversity, generating virus variants that are good at infecting humans.

Ebola

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is a rare but highly deadly disease caused by infection with one of five strains of the Ebola virus. The first outbreak of Ebola was in 1976 near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, periodic outbreaks continue to occur throughout Africa.

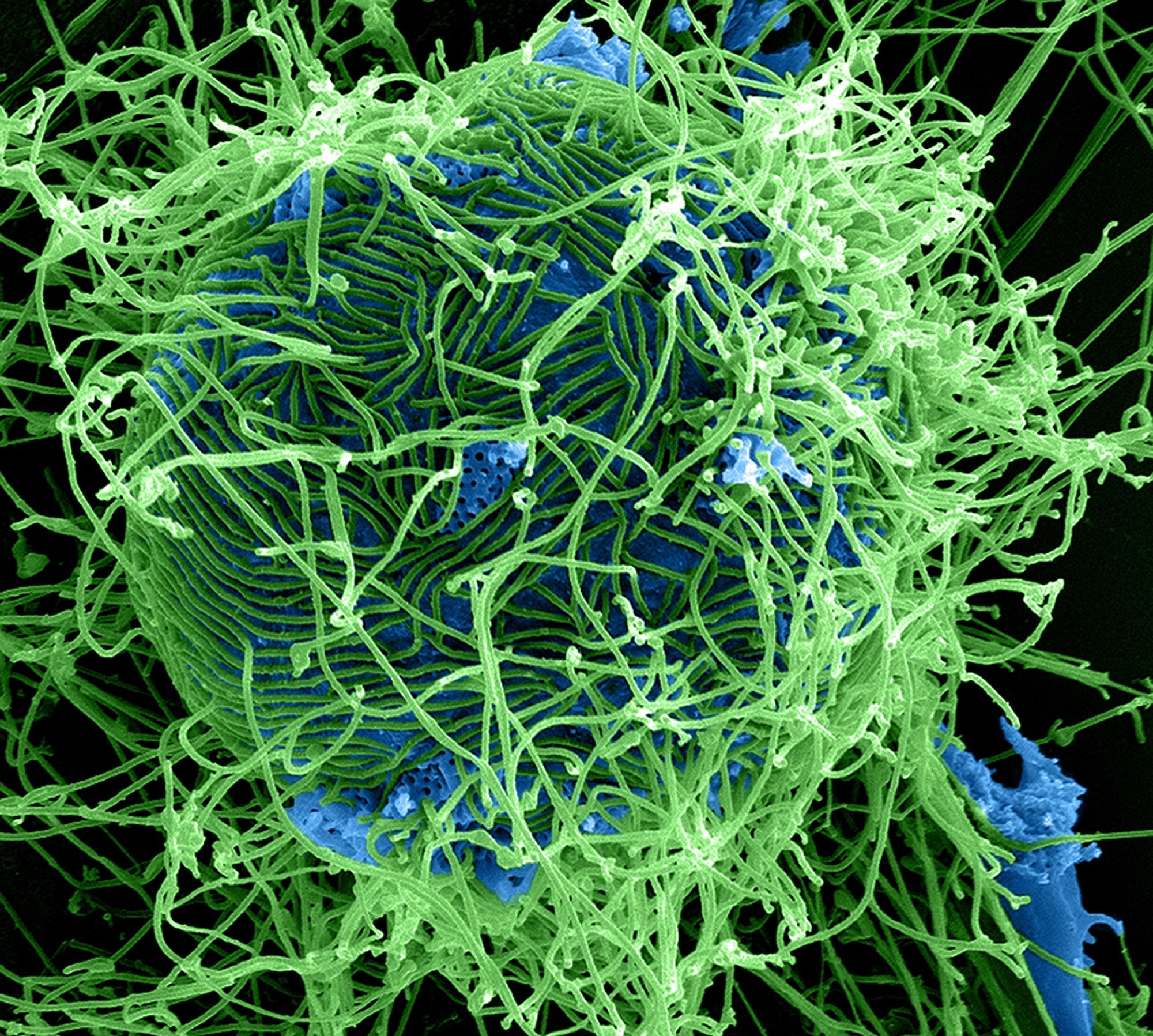

Ebola Virus Particles Colorized scanning electron micrograph of filamentous Ebola virus particles (green) attached to and budding from a chronically infected VERO E6 cell (blue) (25,000x magnification). Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Ft. Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Ebola Virus Particles Colorized scanning electron micrograph of filamentous Ebola virus particles (green) attached to and budding from a chronically infected VERO E6 cell (blue) (25,000x magnification). Image captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility in Ft. Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

The host species for the Ebola virus are thought to be bats, although this has not been proven. Ebola is highly contagious, and exposure to the virus most often occurs through direct contact with an infected patient's blood or bodily fluids. However, it can also occur through direct contact with an infected patient's objects, such as bedsheets, syringes, or clothes.

Although much less common, the virus can also be transmitted to humans through contact with bats or by handling contaminated meat from wild animals. The symptoms of Ebola typically appear 21 days after exposure and include fever, headaches, diarrhea, and bleeding.

In 2014, West Africa experienced the largest Ebola outbreak of all time. Due to its highly contagious nature, the transmission of the virus quickly spread to areas of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.

In total, there were about 26,000 cases of Ebola and nearly10,000 deaths in those three countries over a 1-year period. The 2014 outbreak was particularly serious because it affected urbanized areas, whereas previous outbreaks occurred in remote villages that were easier to contain.

Effective virus control requires extensive surveillance, tracking, and reporting of new cases. In addition, education of the general population is essential for minimizing exposure risk through properly handling infected patients or items and limiting travel.

Avian influenza

H5N1 is a highly pathogenic strain of the avian influenza virus found among domestic poultry stocks in Asia and the Middle East. Outbreaks of H5N1 began in the 1990s, and the H5N1 strain was isolated in 1996 from a goose in China. H5N1 avian flu, which is highly contagious and deadly in birds, spread rapidly throughout Asia.

Although human infection with H5N1 is rare, people can contract avian flu after direct contact with infected birds. The first human cases were reported in Hong Kong in 1997. Since 2003, over 650 cases of human infection with H5N1 have been reported in over 15 countries.

Approximately 60% of people infected with H5N1 have died. Variants of H5N1 have arisen that are exceptionally infectious to mammals and migratory birds. This has led to the virus's rapid spread throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

To date, the avian flu is not spread from person to person. However, the frequent mutation rate of flu viruses combined with the highly pathogenic nature of H5N1 in birds is cause for alarm. Scientists fear a mutated form of H5N1 may arise that is contagious in humans and can be spread through sneezing or coughing, leading to the possibility of a worldwide epidemic.

Conclusion

More intensive and effective surveillance at the animal-human interface, including in the wildlife trade, fur farming, animal slaughterhouses, animal rescue centers, or the veterinary profession, is needed to mitigate future pandemics. In fact, live animal markets pose a danger for emerging zoonotic viruses.

Like social distancing was adopted to dampen the spread of COVID-19, similar approaches should be deployed to better separate humans from wildlife because the large-scale surveillance of wildlife species in nature for potentially pandemic viruses is not feasible.

There should be some form of global pandemic radar with information on sporadic zoonotic events to large-scale disease outbreaks, shared rapidly and freely. To conclude, an increasingly porous human-animal interface calls for pandemic preparedness, which, if not averted, could cost trillions to the world economy in the future.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 6, 2022