Jan 25 2005

A new technique devised by UC Irvine researchers can greatly facilitate the development of vaccines against infectious diseases such as smallpox, malaria and tuberculosis. Because the new technique can synthesize a large number of proteins very quickly, it has potential to accelerate vaccine development, particularly crucial in the fight against bioterrorism.

A new technique devised by UC Irvine researchers can greatly facilitate the development of vaccines against infectious diseases such as smallpox, malaria and tuberculosis. Because the new technique can synthesize a large number of proteins very quickly, it has potential to accelerate vaccine development, particularly crucial in the fight against bioterrorism.

The technique is based on “polymerase chain reaction,” or PCR, and enables the rapid discovery of antigens for vaccines by allowing hundreds of proteins to be processed simultaneously using ordinary laboratory procedures. This new method allows the expression of 384 individual genes – pieces of DNA that contain instructions for making proteins – from a microorganism in just one week. Traditional methods take weeks to produce one protein at a time.

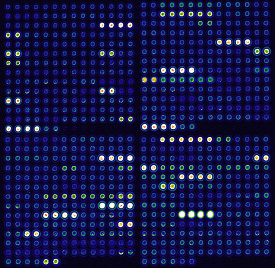

The UCI technique involves loading a microchip with every protein from an infectious microorganism such as smallpox, tuberculosis or malaria. When people infected with the disease react to some of the proteins included in the microchip, laser technology is used to identify these proteins for potential use in vaccines.

The researchers describe their technique in the Jan. 18, 2005 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Technologies today are not able to quickly process large amounts of data that arrive in the form of genome sequences from many human pathogens,” said D. Huw Davies, lead author of the paper and associate project scientist in UCI’s Center for Virus Research. “Our technique addresses and removes this bottleneck. Remarkably, in only ten weeks, we can make every protein of an organism such as the tuberculosis bacterium – which has 3,900 genes.”

The researchers used their technique to identify a unique set of 11 proteins among a total of 200 proteins that make up the live virus that is used to vaccinate against smallpox today. Humans react strongly only to these 11 proteins, explained Philip Felgner, principal investigator of the research project and director of the proteomics laboratory within the Center for Virus Research. “Our method allows us to quickly identify which proteins are responsible for the protective immune response,” said Felgner, a co-author of the PNAS paper.

Scientists currently consider developing a safe vaccine to be the best way to blunt a bioterrorist threat against smallpox and other dangerous organisms that terrorists can use as weapons.

“The existing live-virus vaccine against smallpox produces unacceptable side effects such as allergic reactions, sores, heart inflammation and angina,” Felgner said. “For a vaccine to be an effective defense against bioterrorism, however, it needs also to be safe. With our method, researchers can arrive very quickly at good vaccine candidates that are also extremely safe.”

The research, supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, was conducted in Felgner’s proteomics laboratory. The laboratory belongs to a group of UCI biodefense laboratories developing vaccines and other countermeasures that target infectious microorganisms.

Additional co-authors of the PNAS paper are Xiaowu Liang, Jenny E. Hernandez, Arlo Randall, Siddiqua Hirst, Yunxiang Mu, Kimberly M. Romero, Toai T. Nguyen, Mina Kalantari-Dehaghi, Pierre Baldi and Luis P. Villarreal of UCI, as well as Shane Crotty of the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology.

UCI’s Center for Virus Research in the School of Biological Sciences seeks to foster interdisciplinary scholarship, training and research among UCI faculty by using molecular virology as a foundation for the creation of scientific resources. The center also promotes university-industry collaborations. Current research at the center includes vaccine antigen discovery and the testing of vaccines that use the discovered antigens.