Mar 9 2006

Depression and anxiety disorders during childhood may be associated with a higher body mass index (BMI) into adulthood for women but not men, according to a study in the March issue of Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine.

The increasing prevalence of obesity among children and adults is becoming a public health crisis, according to background information in the article. Understanding the social and psychological conditions that are associated with obesity could help predict which children and adolescents are likely to become obese adults, helping physicians target treatment and prevention efforts. Previous evidence suggests that psychological disorders may be one factor associated with weight gain, but studies in the area have been limited, the authors report.

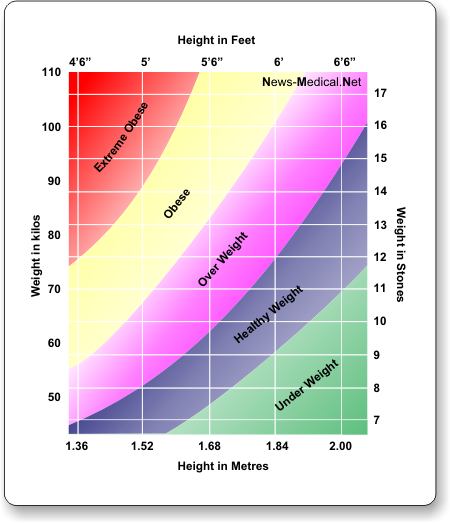

Sarah E. Anderson, M.S., Tufts University, Boston, and colleagues evaluated the association between anxiety disorders and depression and weight gain from childhood into adulthood. They analyzed existing data from 820 individuals (403 women and 417 men) from two counties in New York, who were assessed four times between 1983 and 2003. The participants ranged in age from 9 to 18 years at the beginning of the study, and were 28 to 40 years old at the most recent assessment. At each assessment, the researchers interviewed the individuals to determine whether they met clinical criteria for anxiety disorders or depression. The authors calculated BMI-for-age (BMI z scores) by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters and adjusting it for age and gender based on national reference data. BMI z scores correspond to growth chart percentiles and allow for tracking a child's relative weight through adolescence.

During the study, 310 participants (119 men and 191 women) had anxiety disorders and 148 (50 men and 98 women) were depressed. Women with anxiety disorders had significantly higher BMI z scores than women of the same age and socioeconomic status without the condition. Women with a history of depression were heavier and experienced a greater yearly increase in their BMI z scores than women without depression. Women who were younger when they developed depression had higher weights in adulthood than women who developed depression later.

In women, anxiety disorders were associated with higher weight, with average BMI z scores of .13 to .18 units higher than women without anxiety disorders. For example, an adult woman with history of an anxiety disorder who had an average height (64 inches) would weigh between 6 to 12 pounds more than a woman without anxiety. "Although these average weight differences are not large, obesity results from incremental increases in weight, and successful prevention is likely to require interventions targeted toward many factors, no one of which, alone, is sufficient to prevent obesity," the authors write. An average-height woman diagnosed with depression at age 14 would weigh about 10 to 16 pounds more than a non-depressed woman by the time both reached age 30 years.

Depression during childhood was associated with an initially lower BMI among boys, but over time, the weight difference in depressed and non-depressed men disappeared. Anxiety disorders did not appear to be linked to men's BMIs at any point throughout the study.

The authors suggest that treating anxiety and depression in girls and women may be one strategy in the battle against obesity, the authors conclude. "Our results suggest that efforts to improve mental health in populations may also help prevent female obesity; consideration of the potential for psychological antecedents and correlates of obesity could improve prevention and treatment," they write.