May 25 2009

An international research collaboration coordinated by UCD researchers and involving scientists at 21 institutes including the genome sequencing centres in the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK and the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard, USA have defined six new genome sequences in the Candida fungus family and identified genetic differences in species that cause disease.

The research, published yesterday in Nature, describes how Candida strains have evolved and ensured their survival by adapting their genetic makeup to respond to changes in their environment. Candida species are the most common cause of opportunistic fungal infection worldwide.

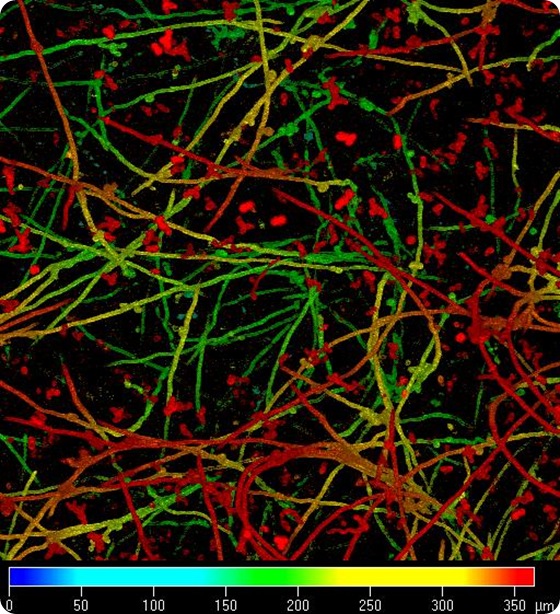

The incidence of Candida parapsilosis in particular poses the greatest threat to transplant patients and premature babies as it forms a film that coats the inside of medical devices such as implants, catheters or feeding tubes. The fungus is drug resistant and the only effective treatment involves the removal of the medical device. Prior to this work, very little was known about this species.

The UCD research team led by Professor Geraldine Butler from UCD Conway Institute & School of Biomolecular & Biomedical Science looked at key components of mating and cell division in Candida species, shedding new light on how the fungi reproduce and survive.

Professor Butler, scientific coordinator on this project, began working to identify the sequence of genes of C. parapsilosis in 2003 through funding from Science Foundation Ireland. She said, "We started by sequencing small parts of the C. parapsilosis genome, which led to our collaboration with the Sanger Institute to sequence the entire genome, and finally to combining this genome with others sequenced by the Broad Institute"

Commenting on their findings, Professor Butler says, "Candida species were originally believed to be incapable of mating, and so may have difficulties in adapting to new environments or new hosts. As a result of our analysis, we now know a great deal more about the evolution of mating, and how some species recombine their genes. Interestingly, C. parapsilosis is probably the only species that cannot mate"

By comparing the genetic sequences in disease and non-disease causing fungi, the team found that in general, the disease causing Candida species have many more copies of genes involved in adhesion, and in the cell wall. The stickiness of the proteins in the cell wall makes it easier for the fungi to adhere to the human host. Further research on the regulation of these proteins may lead to developing treatment methods for infections caused by fungi in the future.