Jun 15 2009

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have demonstrated a new, highly detailed x-ray imaging technique that could be developed into a method for early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease.

The technique has previously been used to look at tumors in breast tissue and cartilage in human knee and ankle joints, but this study is the first to test its ability to visualize a class of miniscule plaques that are a hallmark feature of Alzheimer's disease. Their results will appear in a July 2009 edition of the journal NeuroImage.

Scientists have long known that Alzheimer's disease is associated with plaques, areas of dense built-up proteins, in the affected brain. Many also believe that these plaques, called amyloid beta (Aß) plaques after the protein they contain, actually cause the disease. A major goal is to develop a drug that removes the plaques from the brain. However, before drug therapies can be tested, researchers need a non-invasive, safe, and cost-effective way to track the plaques' number and size.

That is no easy task: Aß plaques are extremely small - on the micrometer scale, or one millionth of a meter. And conventional techniques such as computed tomography (CT) poorly distinguish between the plaques and other soft tissue such as cartilage or blood vessels.

"These plaques are very difficult to see, no matter how you try to image them," said Dean Connor, a former postdoctoral researcher at Brookhaven Lab now working for the University of North Carolina. "Certain methods can visualize the plaque load, or overall number of plaques, which plays a role in clinical assessment and analysis of drug efficacy. But these methods cannot provide the resolution needed to show us the properties of individual Aß plaques."

A technique developed at Brookhaven, called diffraction-enhanced imaging (DEI), might provide the extra imaging power researchers crave. DEI, which makes use of extremely bright beams of x-rays available at synchrotron sources such as Brookhaven's National Synchrotron Light Source, is used to visualize not only bone, but also soft tissue in a way that is not possible using standard x-rays. In contrast to conventional sources, synchrotron x-ray beams are thousands of times more intense and extremely concentrated into a narrow beam. The result is typically a lower x-ray dose with a higher image quality.

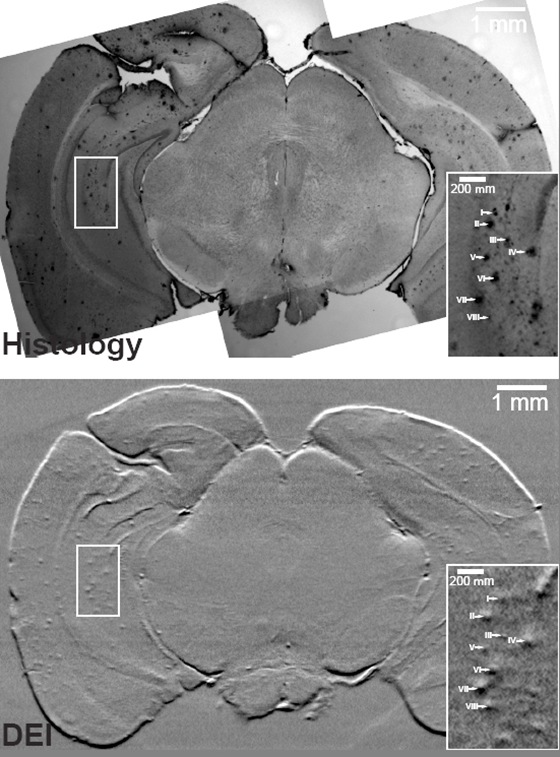

In this study, researchers from Brookhaven and Stony Brook University used DEI in a high-resolution mode called micro-computed tomography to visualize individual plaques in a mouse-brain model of Alzheimer's disease. The results not only revealed detailed images of the plaques, but also proved that DEI can be used on whole brains to visualize a wide range of anatomical structures without the use of a contrast agent.

The images are similar to those produced by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with the potential to even exceed MRI pictures in resolution, Connor said. "The contrast and resolution we achieved in comparison to other types of imaging really is amazing," he said. "When DEI is used, everything just lights up."

The radiation dose used for this study is too high to safely image individual A• plaques in humans - the ultimate goal - but the results provide researchers with promising clues.

"Now that we know we can actually see these plaques, the hope is to develop an imaging modality that will work in living humans," Connor said. "We've also now shown that we can see these plaques in a full brain, which means we can produce images from a live animal and learn how these plaques grow."

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, and Brookhaven Lab's Laboratory Directed Research and Development program. The National Synchrotron Light Source is funded by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences within the DOE Office of Science.

How it works

To make a diffraction-enhanced image, x-rays from the synchrotron are first tuned to one wavelength before being beamed at an anatomical structure or slide. As the monochromatic (single wavelength) beam passes through the tissue, the x-rays scatter and refract, or bend, at different angles depending on the characteristics of the tissue. The subtle scattering and refraction are detected by what is called an analyzer crystal, which diffracts, or changes the intensity, of the x-rays by different amounts according to their scattering angles.

The diffracted beam is passed onto a radiographic plate or digital recorder, which documents the differences in intensity to show the interior structural details.