A team led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) has created the first comprehensive roadmap of the protein interactions that enable cells in the pancreas to produce, store and secrete the hormone insulin. The finding makes possible a deeper scientific understanding of the insulin secretion process—and how it fails in insulin disorders such as type 2 diabetes.

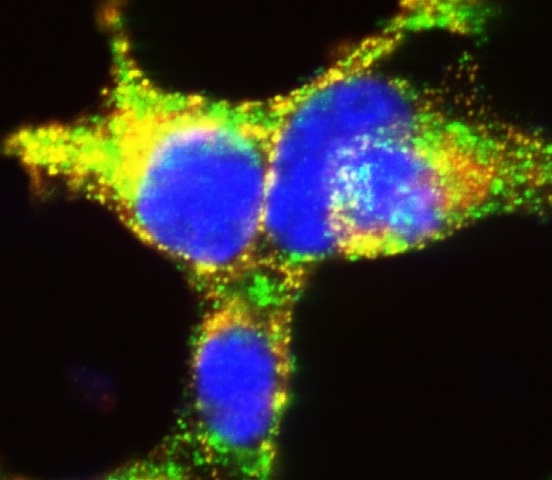

The new study uncovered critical protein interactions in insulin-producing cells. Here, beta cells grown in culture illustrate the importance of TMEM24 in mature storage container granules (yellow) that deliver highly concentrated insulin packets to manage glucose levels after and between meals. (Image courtesy of the Balch lab, The Scripps Research Institute.)

“The development of this insulin interaction map is unprecedented, and we expect it to lead us to new therapeutic approaches for type 2 diabetes,” said William E. Balch, professor and member of the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at TSRI.

Balch was the senior author of the study, which was recently reported online in the journal Cell Reports.

A Widespread Problem

Type 2 diabetes and a similar insulin-related condition known as metabolic syndrome currently affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide. One of the common features of these conditions as the disease develops is the inability of the secretion of insulin by the pancreas in response to mealtime surges of bloodstream glucose to meet demand. Insulin secretion normally signals to cells throughout the body to draw in glucose, which reduces the levels of this sugary fuel in the bloodstream—and a weakened insulin response allows blood glucose levels to stay too high for too long. Chronic elevated levels of glucose in the blood contribute to a wide variety of serious medical problems, including loss of circulation in the lower legs, degeneration of the retinas of the eyes, kidney failure, heart attacks and strokes, and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Boosting or repairing the insulin production and secretion process in the special pancreatic cells, called “beta cells,” where the hormone is made, would seem an obvious therapeutic strategy for type 2 diabetes. However, so far almost no diabetes drugs are targeted at improving the efficiency of this process, in part because so few details are known about it.

Scientists do know that within beta cells, insulin precursor proteins are synthesized, folded and processed into mature insulin as it is packed tightly into ready-to-go containers called granules, and eventually secreted into the bloodstream on demand when glucose levels rise. Researchers also have found and catalogued hundreds of individual proteins that appear to be relatively abundant within beta cells. But such studies haven’t made clear which of these beta cell proteins actually interact with insulin and therefore participate directly in the insulin production, storage and secretion process.

“Our understanding of the beta cell in generating and releasing sufficient insulin, the real culprit responsible for progression of type 2 diabetes, has been extremely poor,” said Balch.

A New View of Insulin

For the new study, Balch laboratory Research Associate Anita Pottekat used antibodies that bind to early and late forms of the hormone in the synthesis/secretion process. By pulling insulin proteins out of the soup of beta cell molecules, these antibodies also isolated whatever proteins happened to have bound to the insulin—and thus presumably had functional interactions with insulin. Pottekat then applied an extremely sensitive form of an established technique called mass spectrometry to identify these proteins.

In this way, the scientists were able not only to determine the insulin-interacting proteins within beta cells, but also to distinguish those that seem to play a role in the early, insulin-synthesis phase of the process from those that seem to function in the later stages of insulin storage and secretion. “We were able to see which proteins appear to be interacting more with the precursor ‘proinsulin’ protein versus mature insulin,” Pottekat said.

Collaborating scientist Scott Becker, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Gerard Manning, then at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, handled the statistical analyses of the data. In this way they were able to assemble what is in effect the first-ever map of insulin’s “biosynthetic interaction network.”

“One thing this roadmap tells us is that insulin effectively runs the beta cell—it is by far the dominant protein in the beta cell and the activities within the cell are largely geared towards its processing and secretion,” said Balch.

“Until now we were identifying one insulin-interacting protein at a time, but this study provides the first systems-wide insights into the insulin synthesis pathway,” said co-author Pamela Itkin-Ansari, a beta cell researcher at the University of California, San Diego and the Sanford Burnham Research Institute, who also noted the research was an example of the highly collaborative nature of the scientific community in La Jolla.

A Potential New Drug Target

Something else was quickly apparent from the mass spectrometry data produced by Pottekat at TSRI: one beta cell protein in particular stood out for its high apparent propensity to bind insulin.

“This protein was clearly very abundant in beta cells, and interacted with insulin at a very high confidence level statistically,” said Pottekat, “yet when we checked the literature, we found that almost nothing was known about it.”

The team followed up with a long series of experiments to characterize the protein, TMEM24, and determined that is involved in the insulin secretion pathway. Beta cells normally secrete insulin granules in an initial brief burst and then in a longer, lower-intensity release. The scientists found evidence that TMEM24, a protein that sits in the membranes of beta cells, effectively regulates this slower, more chronic form of insulin release.

“We think that the discovery of this protein’s role in insulin secretion represents a big breakthrough,” Balch said. “This chronic insulin release appears to be more important for human health compared to the acute release of insulin that protects us from the sugar rush of, say, a Snicker's bar—yet almost nothing has been known about this part of the release pathway.”

The study was done in an established and well-validated mouse cell model of human beta cells. Balch and his laboratory now intend to follow up with studies in human beta cells, both normal and diabetic. “In general, we want to understand more fully what components of this pathway are instrumental in healthy management of insulin production in response to a healthy diet or mismanagement in response to the current unhealthy diets of modern lifestyles leading to disease—and then of course we want to find ways to target those components with therapies,” said Balch.