Sep 29 2015

A new scientific discovery confirms for the first time that mothers-to-be are capable of modifying the genetics of their future child, even when the egg has been donated. Habits of the expectant mother are proven decisive in embryo development and modifying the genome of the embryo, verifying that the maternal uterus influences the baby more than what happens at home after the baby has been born.

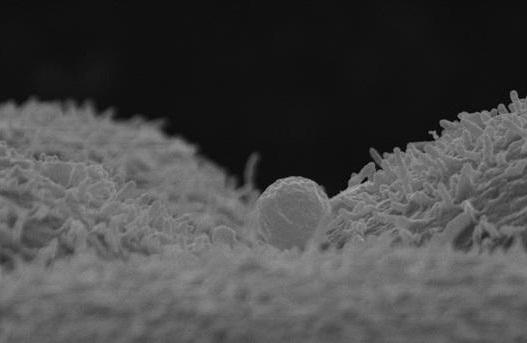

Electron microscope image showing a maternal exosome from human endometrial fluid binding to a mouse embryo cell. The embryo receives the contents of the maternal exosome to establish the first communication between the mother and the embryo in the period prior to implantation.

The study, carried out by researchers Doctor Felipe Viella and Doctor Carlos Simon from Fundación IVI the research arm of leading fertility clinic IVI, has demonstrated that expectant mothers can modify the genetic information of the child, even when the ovum is from a donor or between an expectant surrogate mother and baby. Viella and Simon observed the secretion of Hsa-miR-30-d by the human endometrium, which is subsequently taken up by the pre-implanted embryo influencing its development.

Certain conditions and habits like smoking and obesity can modify women’s cells, including those of the endometrium. This in turn causes changes to the endometrial fluid and its genetic information secretion.

These findings are particularly poignant as it opens the door to hopeful mothers using oocyte donation in order to fulfil their desire to have children, whilst alerting those who opt for surrogacy to the importance of the surrogate mother and the development of the child.

Speaking about the findings Doctor Felipe Vilella says:

These findings show us that there is an exchange between the endometrium and the embryo, which is something that we already suspected as a result of the coincidence of certain physical characteristics between mothers and children born through ovodonation and also due to the incidence of diseases in children related to maternal pathologies during pregnancy, such as obesity and smoking.

This communication may cause specific functions to be expressed or inhibited in the embryo, giving rise to modifications that show us how diseases such as diabetes and obesity are transmitted. As such, this publication opens up the possibility of being able to prevent these kinds of diseases when their cause is epigenetic. Knowing that this transmission exists, in the future we will be able to detect how to interrupt it, putting an end to the trend of obese mothers, obese children. In countries where surrogacy is permitted we will be able to attribute more importance to the history of the pregnant woman’s habits prior to pregnancy.