Up until now, how much has been known about the replication of the H5N1 influenza virus?

A great deal, that of course cannot be summarized in a few phrases, however I would like to point out the significant increase in understanding that resulted from the recent crystallographic structure of Influenza polymerase from the Cusack group in Grenoble, and published in the journal Nature.

What did recent research by scientists from the CEA, CNRS, University Joseph Fourier, the EMBL and the ILL reveal about the molecular function of a protein that plays a key role in the replication of H5N1?

We were able to show that one small domain of the polymerase, the part that is essential for entry of a piece of the polymerase into the cell nucleus, changes its conformation to allow it to interact with the transporter protein than takes it into the nucleus. Without this change in conformation entry cannot occur and viral replication is not active.

Image credit: ILL

What role did nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) play in this research?

NMR allowed to directly visualize both conformations, the conformation that is essential for function, and the conformation that is necessary for entry into the nucleus. These conformations are continually in exchange in solution, and NMR allows us to observe the two conformations at atomic resolution, and to measure their rate of interconversion.

How did small angle scattering (SAS) and single molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) help to elucidate the mechanism?

SAS provides information about the overall shape of the protein in solution, while FRET provides information about long-range distances and the way they change over time (their dynamics). Both of these sources of information are highly complementary to the information derived from NMR.

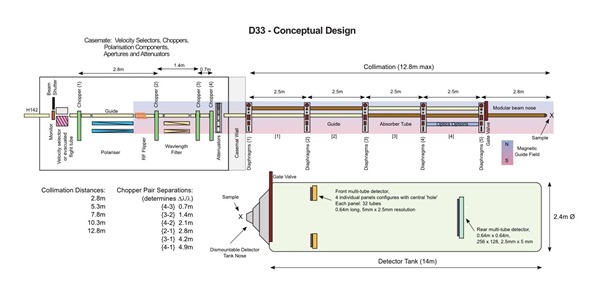

Image credit: ILL

In addition all three approaches can be used to study the interaction between the polymerase and the transporter protein than carries them into the nucleus.

Can you explain the temperature dependency of the ‘open’ and ‘closed’ forms of the protein?

The open and closed forms are in equilibrium in solution, the rate of exchange depends on the temperature: the higher the temperature the more open conformations are present in solution.

Were you surprised by this finding and how do you think it can be explained?

The only conformation that was known (from X-ray crystallography) was the closed conformation, and this clearly could not interact with the transporter protein. We know that the polymerase acts in the nucleus, and that it therefore must enter the nucleus somehow, so we suspected a second conformation or ‘state’ might exist that was different from the crystalline form. Our findings both discover and characterize this state of the molecule.

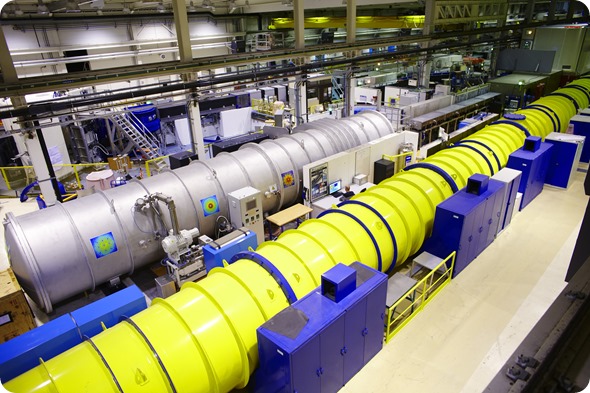

Image credit: ILL

What impact do you think this research will have?

We now understand better how the polymerase enters the nucleus and this opens up new fields of investigation.

How important do you think solution-state structural biology will be in future studies?

Solution state studies are essential, as the cellular environment is also a solution, albeit a highly complex one. Proteins move in solution, and their dynamic motions are essential for function.

Where can readers find more information?

In the article that we have just published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society

About Martin Blackledge

Martin Blackledge is a research director at the Institut de Biologie Structurale CEA-CNRS-UGA in Grenoble. His group uses Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy, in combination with other experimental and theoretical biophysical tools, to study the role of protein dynamics in biological processes at atomic resolution.

He graduated from Manchester University with a 1st class honours degree in Physics and an M.Sc in high energy particle physics, before completing his thesis, developing techniques for localizing NMR spectroscopic measurements in vivo at the University of Oxford, under the supervision of Professor George Radda.

He then spent three postdoctoral years (1989-1992) in the group of Professor Richard Ernst (Nobel prize for Chemistry 1992) in the Physical Chemistry department of the ETH Zürich, where he began studying biomolecular dynamics using NMR.

He then moved to Grenoble where he took a position at the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, and is an independent group leader since 2007. He has published around 190 articles in peer-reviewed journals during his career.